Clean, fresh water is the first and most essential resource when it comes to human health. While progress has been dramatic over the last 20 years, almost ten percent of the world, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa, still doesn’t have access to an improved water sources (i.e. water that is piped into households, public taps, protected spring sources, tube wells dug with a borehole etc.) 1 As such water and sanitation, rightfully so, receives a great deal of funding and attention from the global development community.

In the early 2000’s an innovative charity, PlayPumps International, was set up to tackle this issue through the instillation of their PlayPump systems. Many communities need access to fresh water and many school in those communities have little or no playground equipment. PlayPump International aimed to provide both!

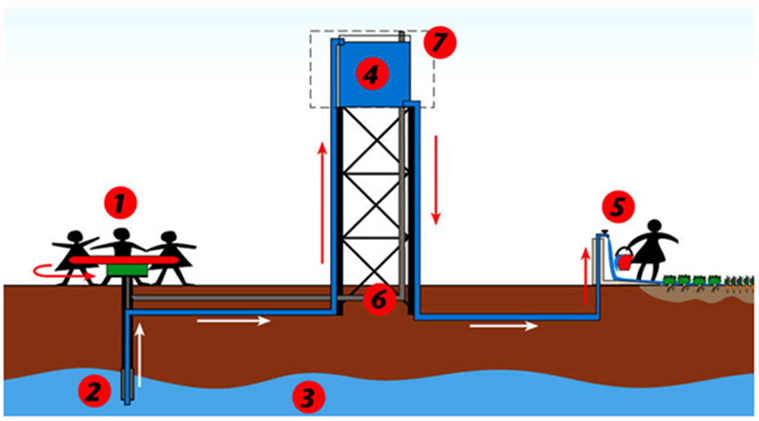

The idea behind the PlayPump is ingenious to say the least. A borehole is drilled and a pump mechanism is connected to a roundabout. During the day children play on the roundabout and this play has the effect of pumping water into a nearby water tower. Member of the community can then simply take their water containers to an outlet near the water tower and collect their water, without having to pump it themselves. The water tower also allows for advertisement space to be sold, any revenue gained from advertising then goes back into the maintenance of the system.

Here is a short video of the PlayPump in action:

Lovely idea, right?

When PlayPump International launched their publicity for the project many people thought so.

In fact it’s hard to get across just how much the international aid community got behind the idea. Millions of dollars were raised from Laura Bush and AOL Founder Steve Case. Jay-Z even raised $250 000 for the project through a gig specially for PlayPumps2.

The intention behind the PlayPump was commendable, providing fresh water to a community that has none while also proving play equipment for the kids. The issues with the intervention however were so extensive and so catastrophic that now the PlayPump has become synonymous with the idea of an ineffective, even damaging, aid intervention.

On paper it sounds great. Even on video it looks great! But reality is a different beast and one that is rarely kind to good intentions, little planning and no testing.

Ever since PlayPumps started to be installed in the late 90’s there were rumours around them perhaps not performing to the shiny and happy level that PlayPumps advertising would have you think. However it wasn't until around the late 2000’s that the evidence demonstrating issues with the intervention came to light.

Problem 1: Basic maths, physics and engineering

A PlayPump costs approximately four times the more standard Zimbabwe Bush Pump. This, on its own, is not a problem, perhaps the PlayPump’s were more efficient at pumping water to the surface than those pumps.

They weren't.

To get liquid up out of a boar hole an up and down stroke movement is needed. With a standard long handle pump, hard and powerful strokes with a lot of force are possible*. However, with the horizontal rotation of a roundabout, this rotation needs to be converted into a vertical pumping mechanism. This was achieved with a sort of half corkscrew and drop (see pictures right).

As such the PlayPump was horrendously inefficient (and also not like a normal roundabout to play on, clunking on every rotation and lacking in momentum), averaging out at around 245 litres per hour compared to around 1300 litres per hour for the Zimbabwe Bush Pumps3.

So not only were PlayPumps 4 times as expensive, they were also 4 times less efficient.

Problem 2: Ignorance of problem 1 and pushing ahead anyway

A minimum water requirement for an adult being served by a community pump (i.e. drinking, cooking, hand washing water) is around 15 litres per day 4.

Take a look back at the video earlier in the post. I count around 25 children there. Therefore it would take around 1 hour 50 mins of “play” on the PlayPump to provide just the people in the video with enough water for the day. Even being generous and halving that number (due to the fact that they're children) there won't be much water left for the rest of the community at the end of the day.

Also, I don’t know about you but when I was a kid around 10 minutes was enough roundabout time for me, imagine having to play on one every day for a couple hours just so you and your family have fresh drinking water. Fun quickly stops being fun when it’s vital for your survival.

This again would have been fine if it were supplementing a existing pumps.

Problem 3: They removed perfectly workable existing pumps and replaced them with PlayPumps

A survey of 100 PlayPumps was conducted in 20075. Of these 100:

- 29 had been installed on new boreholes and the remaining 71 had been installed on existing holes

-- 28 were replacing pumps that had stopped working and

-- 43 were replacing working or easily fixable pumps

Problem 4: Put it all together and what have you got…

You have imagery like this:

When you have one pump serving a community of a few hundred people and are relying on child labour to pump water inefficiently the job will eventually fall to the women of the village (because this is where this kind of work always falls).

According to comments from PlayPump users, the pumps were in constant use by women for around 6-12 hours a day. They were painful to use, as they were designed for the height of children, the elderly or pregnant found it particularly difficult, not to mention how undignified and humiliating it was for the women that could use them.

Also the final kick in the teeth was the water tower. Each inefficient turn of the wheel was made even worse as the water had to be pumped an extra 20 feet, against gravity, up to the water towers.

Here’s a quote for an investigator that sums up the futility of the PlayPump:

”With every rotation I could hear a small splash of water in the tank, followed by a splash of water into the lady’s bucket on the ground beside us. Because the tank wasn’t full (which I figure they almost never were), the lady was essentially having to exert herself to move the water 20ft upwards, just to have it come back down again. I don’t know what you think, but to me it seemed like a bit of unnecessary extra effort to fill a bucket.”

Moral of the story

This story illustrates the importance of testing an intervention before adopting it, even if it logically sounds like it would work. Shoddy interventions can then be shelved and successful interventions to be scaled accordingly.

PlayPump International were not wrong to try this idea, they captured people's imagination and got them to donate a huge amount of money. The only issue was that the imagination that was captured was based on a lie.

Not all charities are equal in the good they can do, but this shouldn’t mean that we should become cynical and jaded towards charity we just need to optimise a little better and perhaps question our motives towards giving. Are we giving to make ourselves feel good or are we giving to genuinely make lives better for others? If it is the former we run the risk of falling for the PlayPump, if it is the latter we may want to consider taking an extra 5 or 10 minutes out of our day to check that we are giving in the most effective way possible. The website GiveWell is a fantastic resource that can help you towards this end.

So to answer the title question: Oh dear god no, let's fund interventions that work instead

*There was no way for me to write this section without it sounding dirty as all hell, so I thought I’d lean into it.

About me:

My name is Richard, I blog under the name of @nonzerosum. I’m a PhD student at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. I write mostly on Global Health, Effective Altruism and The Psychology of Vaccine Hesitancy. If you’d like to read more on these topics in the future follow me here on steemit or on twitter @RichClarkePsy.

Referenced Sources:

[1] Our World in Data: Water access resources & sanitation

[2] Look to the Stars: Jay-z fundraising for PlayPump

[3] Objects in Development: Ten problems with the PlayPump

[4] Sphere Handbook: Water supply standard

[5] Obiols, A.L. & Erpf, K. 2008, Mission Report on the Evaluation of the PlayPumps installed in Mozambique, Centro de Formação Profissional de Àgua e Saneamento, SKAT, Mozambique.

Additional sources:

The Guardian: Africa’s not-so-magic roundabout

Humanosphere: How PlayPumps are an example of learning from failure