This is the third part of a little series of articles reflecting on the past year -- my first as a full-time permanent resident in Japan. You can read part one here here and the first half of part two here.

Because my first attempt at describing the time I spent as an intern on a Japanese farm in Nagano 長野 ended up being a little bit too pessimistic for my liking, I decided to balance it out with an additional article focusing on all the nice stuff. Since the first half of this two-piece look at my farming apprenticeship was called Part 2a, this second half will be called Part 2b. (Sorry if I'm confusing you). Hopefully, the two taken together will give a better and more fair idea of what it was like to work as a Japanese farming apprentice for a full season.

Again, you can read the previous parts here:

Looking back and looking forward, Part 1: Learning to Drive

Looking back and looking forward, Part 2a: Farming in Japan, The Tough Stuff

1. The views

This may seem overly obvious and therefore not worth mentioning, but most farming is done in the countryside. And the countryside tends to be where the best views are. Ergo, a farm in the countryside is invariably a good place to be if you like nature and enjoy good views. The farm I worked on -- in the mountains of Nagano, Japan -- was not so much different as exceptional: situated on the edge of a small plateau it overlooked a plain below (where the closest city was located) and faced a mountain range complete with permanently smoking volcano.

But working outdoors and getting to admire the natural surroundings isn't just about getting to look far ahead. In fact, one of the most impressive views is not in front, but above: the sky, when you are under it all day, and when you pay it some attention, is at once vast and perfectly detailed. Bright blue, bright pink, clear as day or streaked with clouds, the sky is amazingly expressive and taking the time to look at it and get to know it is undoubtedly one of the first and most important steps to reacquainting yourself with the natural rhythm of the universe: working outside all day it becomes easy to understand why in the past no watch was needed to know when to cover the crops to protect them from the cold night ahead, when it was time to go for lunch or to leave for home; why no weather station relaying info 24 hours a day was needed to know what the weather would be like the following day.

The sky is not just expressive, it is a very moody thing: not just because it has a mood of its own, but because it has a huge influence on the mood of those who are aware of it and who work under it. Dark storm clouds, and clear uninterrupted blue, the fiery red of a winter sunrise, or the subtle pink of a summer sunset, all affect and modify -- for better or for worse -- the disposition of the farmer, filling him with hope for a good harvest, dread of the tempest ahead, sadness at the death of summer and joy at the birth of summer.

When you can see the sky all day long -- and it can see you -- then you naturally and unconsciously attune yourself to nature and to her rhythm, and working and resting both become easier and more spontaneous. This is something the Japanese seem to appreciate more than Westerners: not only because the have no such thing as daylight saving time and thus follow nature on her intended course all year round, but because the language is full of references to the seasons and to its respective weather patterns (whereas in English the seasons are named in purely numerical fashion, the traditional Japanese names refer to such things as the falling of the leaves in autumn (hazuki 葉月, August) and the blooming of the u-no-hana 卯の花 flower in spring (uzuki 卯月, April)).

2. The Wildlife

Another aspect of working on a farm which may seem obvious but nonetheless deserves mention, is the proximity to seemingly innumerable forms of wildlife. Living in the city it can sometimes be tempting to think that man is alone in this world, that when there is not another human being close by that we are not alone. But when you work in the countryside - and in particular on an organic farm where life is valued, not reduced to a minimum in the interests of monoculture -- it is painfully obvious that being on your own is in no way synonymous with being alone. Indeed, working on your own -- which is common for a farmer -- often has the opposite effect: the less we are surrounded by other human beings, the more we are aware of the other life forms that surround us. Bugs, caterpillars, spiders and crows were, on the farm where I worked, the most obvious and regular companions, but a whole host of others were continually hinting at their presence through tracks, nests, galleries dug under vegetables and other similar signs: moles, voles, rabbits, deer, foxes, badgers, snakes and who knows what else.

Somewhere between that of man and the genuinely wild and undomesticated there is a world of tame and generally friendly creatures: the farm animals. Whilst they may not share the awe-effect of the wild beasts that roam discretely around, they nonetheless remind man of his place in nature, lest he ever forget that he is vastly outnumbered: even on farm such as the one I lived on which was specialised in vegetables, the farm animals outnumbered the humans by at least five to one.

One of the most free and -- in my case -- the most vociferous of these was the farm cat: named Shichi (し "shi" for shiroi 白い -- white -- and ち "chi" for chairoi 茶色い -- brown) she was clearly unintimidated by anyone or anything. Totally at ease wherever she went, she would gaily spread herself out on top of freshly planted seedlings or on the row-cover, flattening the plants beneath them, and often ran about at night on the roof of the small hut I lived in, but she was an effective mouser and very pleasant company.

Coming from Scotland, there were a great many animals, bugs and beasties that I had never encountered before. I may have been familiar with frogs, toads and mice, but snakes, praying mantises, exotic spiders, cicadas and massive long centipedes were all new -- and slightly intimidating at first -- to me.

3. Farming

The views and everyday encounters with wildlife were wonderful, but they were not the reason I was on the farm: I was here to work and work I did! In exchange for a mere 10,000 yen a month plus free accommodation and one meal a day, I put in 12 hours a day, six days a week and was teamed up with the one full-time member of staff that the farm employed (in previous years there had apparently been as many as three or four interns at any one time, but last year I was the only one). There were no classes, no presentations, just work: what had to be done was done, and so I learned the ropes as I went. The lack of rest -- or indeed simple enjoyment taken -- came as quite a shock, having only ever farmed organically in France up until then, and many of the techniques I was shown went totally against what I had come to accept as good organic farming practice, but there was still plenty of pleasure to be taken, albeit on my own and in small doses so as to not interrupt the work flow.

Indeed, one good thing about farming is that you really don't need to go looking for beauty and interest: it is all around you and comes at you as you work, ready or not. As farm work is basically half putting plants into the ground and half pulling others out, a lot of time is spent with your hands in the soil. While the Japanese do not seem to have the same close relationship with the soil that I had known in France -- in Japan, white rubber surgical gloves are the norm --there was still plenty of opportunity for getting down and dirty. This in itself is a good thing -- it has been scientifically proven that getting your hands in the earth releases good hormones and is all over good for both the mind and the body -- but pulling out what is in there often brought pleasant surprises as an added bonus. Personally, I am quite fond of carrots and was forever delighting in the strange twisted forms -- like lovers locked together in a passionate embrace -- they would often take. While these "deformed" roots were always set aside (for the family's personal consumption, or for making juice) and never sent to the customers, they struck me as far more beautiful and entertaining than the regular, ideally shaped specimens. And the taste, too: I received any number of these rejects to cook with in my cabin, but very rarely got round to it, preferring instead to munch on them as they were, with no more than a little mayonnaise or miso to flavour them.

Later on, in autumn, as other crops were brought in for winter storage, I got to follow their evolution out of the soil: millet, for example, was hung up in a hoophouse to dry thoroughly (before separating the grains and storing away for winter), the colour changing slowly but surely from green to copper to gold, seemingly mirroring the changes in the forests around us.

Stocking up for winter, hanging millet and onions, bagging turnips and beets, soy and hanamame 花豆 beans stacking crates sweet potatoes and Chinese cabbage, and dozens of other varieties vegetables both strange and familiar, also brings a certain kind of satisfaction quite unrelated to simple aesthetic enjoyment. Simply knowing that there is food for the winter ahead, that the year's hard work was worth the effort, and that what has been brought in in time for the first frosts (or just after, in the case of certain specific crops) will continue to improve in the cellar, is in itself a thoroughly rewarding experience.

Most jobs on the farm had us working pretty much in close proximity: even when we were too far apart to talk to each other, we could see each other and so, when there were breaks we would take them together. Some other tasks, however, such as cutting the weeds growing amongst the soy beans, had me on my own in a far off field. When that happened, I would take a break on my own, sitting down for a few minutes to cool down, drink a little water from my beat-up flask, and munch on a biscuit. This was always very satisfying: refreshing yourself after hard work is so much more rewarding and enjoyable than just routinely feeding yourself for the sake of it. It was also always a good chance to look closer at the nature around me: all the life in the grass, for example, that we do not normally see. Or quite simply to look at what was immediately in front of me: with such stunning views, it was tempting to be always looking far away, so observing things closer to home was very often a peasant change.

Something else I got out of farming for a year in Japan was better health. Working hard outside all day and eating nothing more than rice, miso 味噌 soup and lots of vegetable made me lose a lot of weight: somewhere between 15 and 20 kg over the course of the year. To be fair, I was at my heaviest before coming to the farm -- spending the best part of six months in Tokyo doing little more than eating, drinking, and playing the tourist didn't do me any favours -- but the change was still very welcome. I also became more aware of how my body responded to different foods as having a basic diet of vegetables, miso and rice made me much more sensitive to anything much else: I noticed, for example, that when I ate a lot of miso I didn't smell, no matter how much I seemed to sweat in the hot summer months (this seems to be a pretty much accepted benefit to eating miso, not just something peculiar to me). I also lost the habit of eating meat and, when I did eat some on my bi-monthly return trips to Tōkyō 東京, I quickly became tired and felt full and uncomfortable. One more reaction I developed -- much more serious this time -- was an intolerance to processed sugar. Eating sweets on breaks or on the bus back to Tōkyō (it's very hard to find anything that doesn't contain sugar in a convenience store or highway road stop) made me sluggish and on more than one occasion made my eyes go funny, impeding my sight and also making me slur my speech. I had one "fit" the night I arrived in Tōkyō, one time, that left me momentarily unable to either comprehend what my wife was saying to me or speak: all I could hear, and all that came out of my mouth was gobbledygook. Not a nice experience, but one that made me much more aware of my body's needs: while the farming-apprentice life was hard, it was obviously cleaning me out and highlighting all kinds of sensibilities and intolerances that my body had probably been struggling to get me notice for a long time...

4. Visiting Other Farms

Once I had been on the farm long enough for it to become clear that I would be staying for the year, and that I could do the work, I was asked if I wanted to help out on a few neighbouring farms, to get a feel for what other people were doing in the area. As I was desperate for the opportunity to get out and about (for the first four months I didn't have a car so I was stuck on the farm), I immediately said yes. I ended up visiting only two farms, both run by former apprentices on the farm where I was, but many years before me: Kusabue-nōen くさぶえ農園 and Fujii-nōen 藤井農園. Despite both working in much the same way as the farm I was on -- essentially growing "organic" vegetables from non-organic i.e. without chemical fertilisers, pesticides or herbicides -- they were both slightly different.

Hayashi-san 林さん, the owner of Kusabue-nōen had finished his internship some twenty years before me so he was already much more experienced even than the people I was working with (who had taken the farm over only six years ago) and had a very different style: he was very fast, very dynamic, much more fun to work with and was married with three kids. It may have had something to do with the fact that his wife kept bringing out home-made cakes, but I really liked working at Hayashi-san's place and I think it was good for me to get a break from where I was doing my internship. Despite not be quite as obsessed with organic seed as I am, or as interested in natural farming-type techniques, his working style suited me well: he obviously did a lot of preparation, calculating things in advance, carrying around his excel sheets on his smart phone and having everything where he wanted it to be, but then getting what had to be done done really quickly and slightly slap-dash without worrying about getting it exactly right. He made me remember those lines of Curtis Stone that I quoted in my last article:

"for optimum effectiveness, abandon perfection," "perfection is not worth the time" and, above all, "it takes 50% of your > time to achieve 85% effectiveness and quality; it takes the same amount of time to get the further 15%: is it worth it?!"

Which struck me as the total opposite of the way things were done on the farm where I worked: rather than doing anything in advance, everything seemed to happen on the spur of the moment, and was obsessed over, needlessly taking up time and energy and causing stress. Realising this was one of the key moments of my first year in Japan, a first step towards really integrating my experience gained from my former life in France with my new life in Nagano.

Fujii-san 藤井さん, whose farm was only a few kilometres away to the east, was much younger -- he had finished his internship about ten years ago -- but it was more his style which was different: a Tokyo University graduate, he obviously had a head for figures, for business and for hard work, and was more aware of cutting edge technology (for example, he used a paperpot seeder for a number of his crops), but was a lot less communicative and laid back. His farm, too had a different feel to it: whereas Hayashi-san's place was sandwiched cozily between two strips of woodland and his house was typically Japanese in style, Fujii-san's land was much more exposed (which also meant a better view) and his house -- a western-style log cabin -- built on top of a small hill. I am sure most "serious" Japanese farmers would consider Fujii-san to be a more accomplished -- and probably more modern, too -- example of the profession, but I preferred Hayashi-san's approachability.

5. Food and Drink

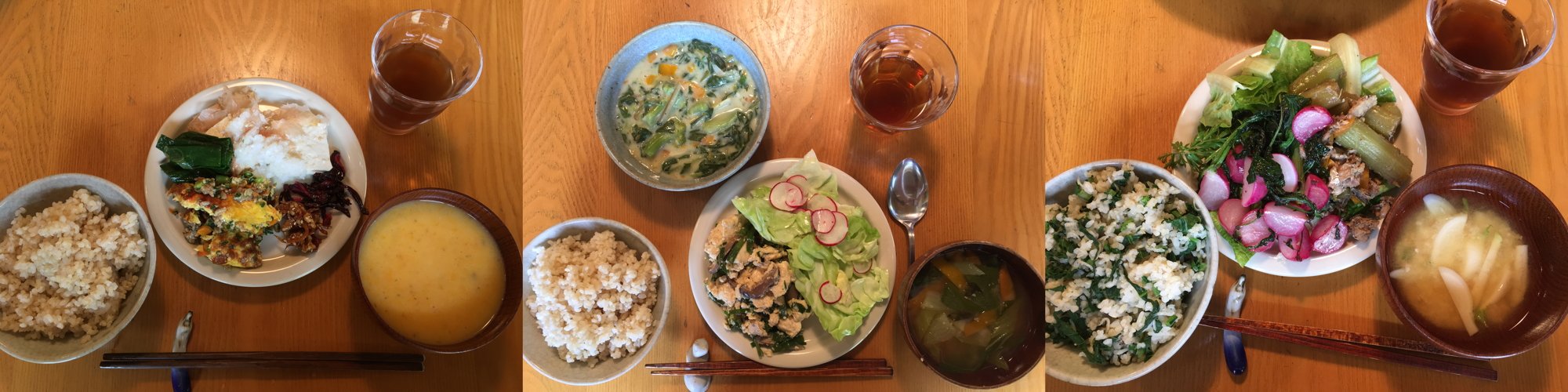

The average Japanese farmer's diet is quite different to that of their European or American (I assume) counterparts: whereas any farmers I have known in Europe were pretty much big meat-and-potatoes eaters and consequently physically bigger and heavier, in Japan the profile is much leaner, lighter and the food much more vegetables, rice and miso 味噌 based. This made for a quite intense transition: going from bread, butter, milk, meat and potatoes to rice, soy sauce, miso, vegetables and tofu 豆腐, all the while at the same time putting in more longer and harder work-days, was not easy, but it did open my eyes further to simple -- and good -- food. Because I did not have a car for the first few months of my internship I relied on what ingredients I was given to cook with (rice, tofu, apple juice -- a Nagano speciality -- soy sauce, cooking sake and as many vegetable rejects as I could eat from the cellar) for breakfast and dinner, and shared lunch with the rest of the farm.

But, as a farmer, it's not just at meal times that you get to eat: being literally surrounded by food all day long means that you can in theory grab a bite to eat whenever you want. While everything might not be at it's best raw, plucked from the earth it grew in, it would probably surprise most people just how much stuff can be eaten as it grows. Carrots and tomatoes are obvious examples, but there are many other varieties -- such as kale and turnips, usually cooked -- than can be eaten raw when they are grown properly. And, if you are a little adventurous, you can go further still and chow down on some "weeds" (or, as we call them in permaculture, "pioneer plants"). That may sound crazy but, in actual fact, many modern "weeds" were consumed as food for a long time in the past and are actually just as (if indeed not more) nutritious than the modern cultivated varieties that have replaced them in our daily diets. Two examples that were very easy to find on the farm I worked on are dandelions and purslane. Both are considered by most people (farmers and non-farmers alike) to very definitely be undesirable in the garden or farm, but are also much appreciated by foodies and chefs: when I lived in Paris, one greengrocer sold dandelion alongside their other vegetables, and I ate purslane (pourpier in French) more than once in some of the most famous restaurants. Along with being very nutritious and possessing medicinal qualities, there is the added benefit of being able to munch on them at will without ever having to worry about being given a row by the farmer!

6. Studying at Agricultural College

As an official farming apprentice, enrolled in the system, I was entitled to participate on a government-funded course in organic farming at a local agricultural college. I wasn't too keen at first, having already studied organic farming in France, but I went along to see what the Japanese approach to organic farming was, and to acquaint myself with some of the terms. The classes weren't particularly long, or very often -- one afternoon every two weeks for three months -- but it was a strange sensation getting to sit down for such a long stretch at any one time after such a long time on the farm (you don't do a lot of sitting about as a farmer!), and it got me off the farm.

長野県農業大学校野菜花き試験場佐久支場

(Nagano Prefectural Agriculture College: Vegetable and Flower Experiment Sub-centre)

As well as classes on pest-management, crop rotation, no-till systems, compost and all the other usual subjects, we got to visit two organic farms run by two farmers with very different set-ups, the idea apparently being to give us (there were about 20 of us) as varied an idea as possible of what organic farming is and could be.

The first farm we visited was basically two fields: one of physalis (400 plants apparently) and another of courgettes (about 3000 sq m). Although Iwase-san 岩瀬さん farmed without chemicals, only the physalis field (a former rice paddy that had given him problems in the first year) was certified organic, as his clients for his other products didn't see the need for certification and so he didn't want to spend the required (to obtain certification) needlessly. Most of the fertilisation was done by sowing green manure (rye and sorgho) in autumn and turning it in in spring, and he did nothing particular to counter pests other, perhaps, than an electric fence to control deer coming in to eat his courgettes. But he seemed to be struggling: he had only been farming for a few years, he wasn't making much money, was doing most of the work himself and was obviously relying on one big client (who took his courgettes) for survival. He was obviously supposed to be example of what it would be like for us as new farmers on the block, struggling to make ends meet and working crazy hours.

The second farm, run by Maki-san 真木さん, was a different affair. The visit started not in his fields but in the classroom with a 45 minute powerpoint presentation of his company, his vision and his farming techniques. Here was someone who was clearly a businessman, who knew how to grow and how to run a farm, but who also knew how to sell, both himself and his products. In his own words, his outfit wasn't so much a farm as a venture-kaisha ベンチャー会社, a venture company. The actual company name was Field is the limit and the motto, in rather dodgy English, was "love mission! love passion! high tension!"

But despite this obvious knack for good business, he was also clearly totally on the ball from a farming point of view sharing some techniques with some of the most successful farmers in the US and Canada: he practiced "living mulch" (using barley and other cereal crops as mulch in the pathways between beds) and he didn't leave his tomatoes and courgettes on the vine until the very end, preferring to turn them in "whilst they still have some energy to return to the soil." Just like Iwase-san he worked crazy hours (he had arranged things so that the visit would take place during his lunch break), but unlike Iwase-san, he was making money and employing people: with a 12 man team he was currently doing 40,000,000 Yen (about 300,000 euros) in sales and was expecting to double that in the next two years. Although I didn't quite understand everything he did, he was the closest thing I had seen to the kind of farmer I intend to be and was farming as close to the cutting edge as anyone I had seen in Japan so far.

Conclusion

While my year working on a farm in Nagano was still one of the hardest things I have ever done, I wouldn't have been able to do it had there not been some serious enjoyment to be had also. If the bad memories are still present in my mind it is most probably because so little time has passed: I am sure that years from now, what I will best remember will on the contrary be the good stuff, the pleasant things I got to try my hand at, the time spent out under the wide, open sky, and the people and animals I met. So, although it may still be a little hard to think positively of the hard times, I am truly thankful for the good times and to the people I worked with for making them possible.

When he's not obsessing over heritage varieties of vegetables & herbs, chasing off wild deer or otherwise running around the fields of his mountain farm, he's trying to beat the system, taking photos or trying to better understand cryptocurrencies.

You can find his Steemit introduction here

You can find out more about his farm here: @potagerdescerfs