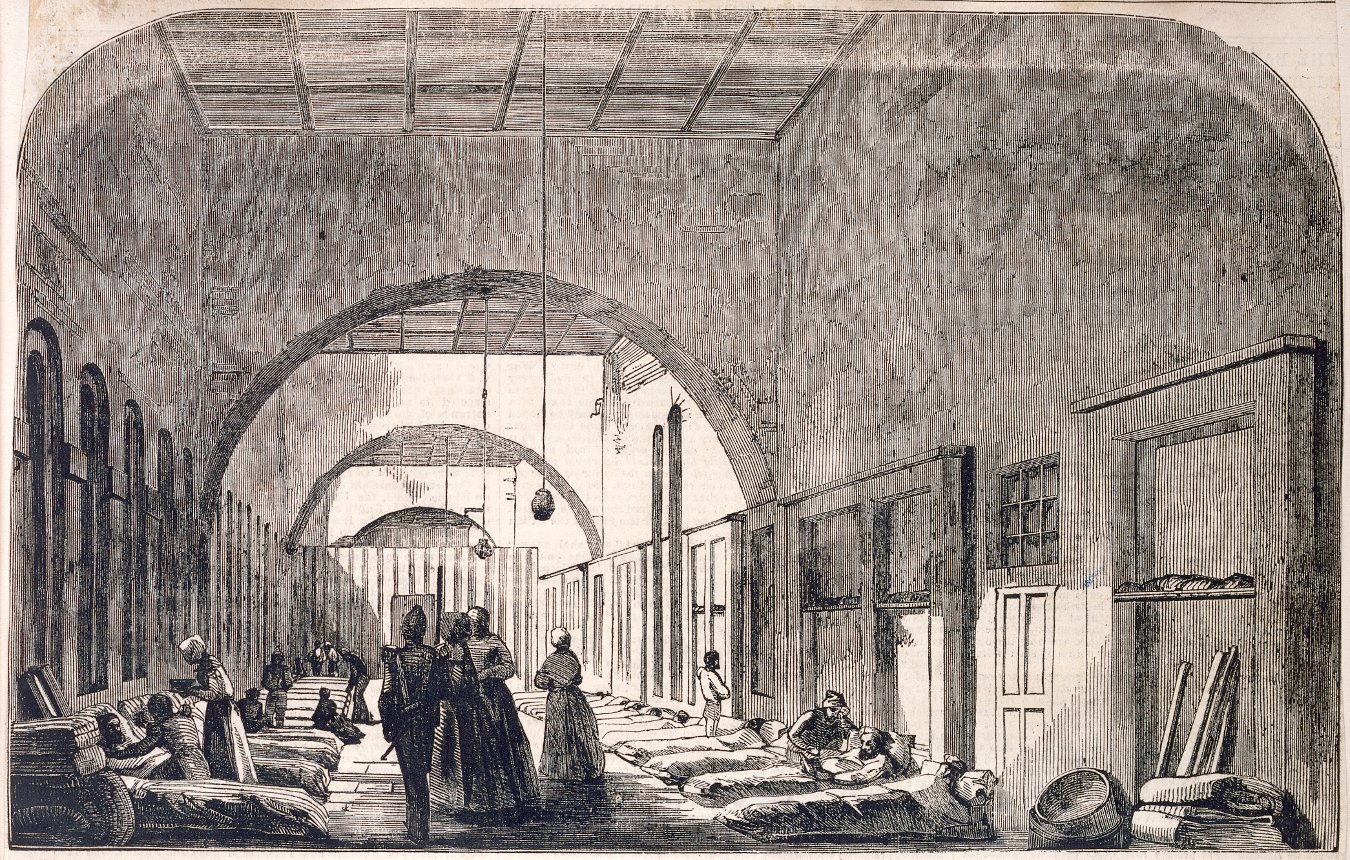

This picture shows Florence Nightingale ministering to the sick at Barrack Hospital, Scutari, during the Crimean War (1853-1856). One newspaper report described how she would make her rounds after other military officers had gone to bed.

A few days ago I published a blog about new developments in psychiatry. I began the blog by describing the fate of a ten-year-old child, Giovanna M., who was committed to a hospital with the complaint of a headache. She spent the rest of her life in confinement because she was judged to be mentally ill. Giovanna's history appeared in an article that detailed the diagnosis of hysteria in women. Then I remembered something I'd read about Florence Nightingale. Few women in history have achieved the name recognition of this accomplished nurse. And yet, many historians and physicians, over the years, have suggested that Miss Nightingale suffered from hysteria. It was no coincidence that celebrated Florence Nightingale and humble Giovanna were female. Hysteria was considered to be a distinctly female malady.

The long-held bias against the womb may have had its origins in a notion of the ancient Greeks, who believed illness in a woman was caused by a 'wandering womb'. The word for womb (uterus) in Greek is hysterika. The womb was supposed to wreak havoc as it wandered into places it did not belong.

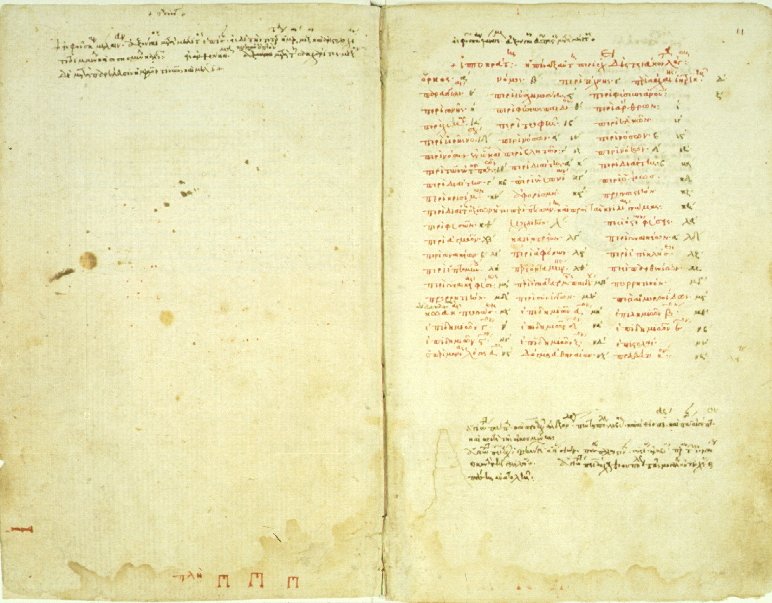

This picture shows a copy of the Hippocratic Corpus manuscript. In this compilation of medical advice, the phenomenon of the "wandering womb" is explored. The hand-copied manuscript dates from 1525. It is in the public domain because its copyright has expired.

The idea of a wandering womb reappeared in the Middle Ages, when sneezes were deliberately provoked with strong scents to chase the womb back to its proper place. By the time Florence Nightingale came upon the scene and took to her bed for all of fifty years (yes she did), it was understandable that people might assume she was suffering from hysteria. What is more difficult to understand is that even in recent years there have been reputable people who diagnosed Florence Nightingale with hypochondria, or some sort of 'hysterical' illness.

Florence Nightingale is shown posing with a group of nurses at St. Thomas Hospital in London. After she returned from Crimea, Miss Nightingale founded a nursing school at the hospital. The picture is credited to FormerBBC and is used under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

It is fascinating (in a regrettable way) that without firm evidence, commentators confidently throw a shadow across the biography of one of the most consequential women in history.

If one were to undertake the task of diagnosing the long-deceased, how might that investigation proceed, in order to be responsible? A good beginning would be to consider Miss Nightingale's history, as a doctor might on first encountering her. The last time I went to an emergency room, for example, one of the first questions the doctor asked was, "Have you traveled to a foreign country recently?" She also asked, "Have you eaten anything that might have made you ill?"

Although much about Miss Nightingale's life must necessarily remain shrouded, because she is no longer with us, these two questions can be answered. Florence Nightingale did travel to a foreign country, and she did definitely eat food that might have made her ill. Two solid clues, out of the miasma of subjective impression.

In order to place Miss Nightingale's illness in context, it is necessary to explain the circumstances that surrounded her illness. In 1854, Britain was engaged in the Crimean War. Some historians have called this the first modern war. It was certainly modern in two respects: new forms of weaponry inflicted harm with greater efficiency, and the telegraph service reported an ominous death toll to folks back home. The telegraph also delivered other startling news: More soldiers were dying in military hospitals than were actually killed in battle. This was a disgrace to the War Department and, alarmingly, the tremendous loss of life was impeding the war effort. R. Sidney Herbert, who headed the War Department, was a friend of Florence Nightingale. He was aware that she had done good work in a local civilian hospital. Herbert wondered if she might be helpful in a military hospital.

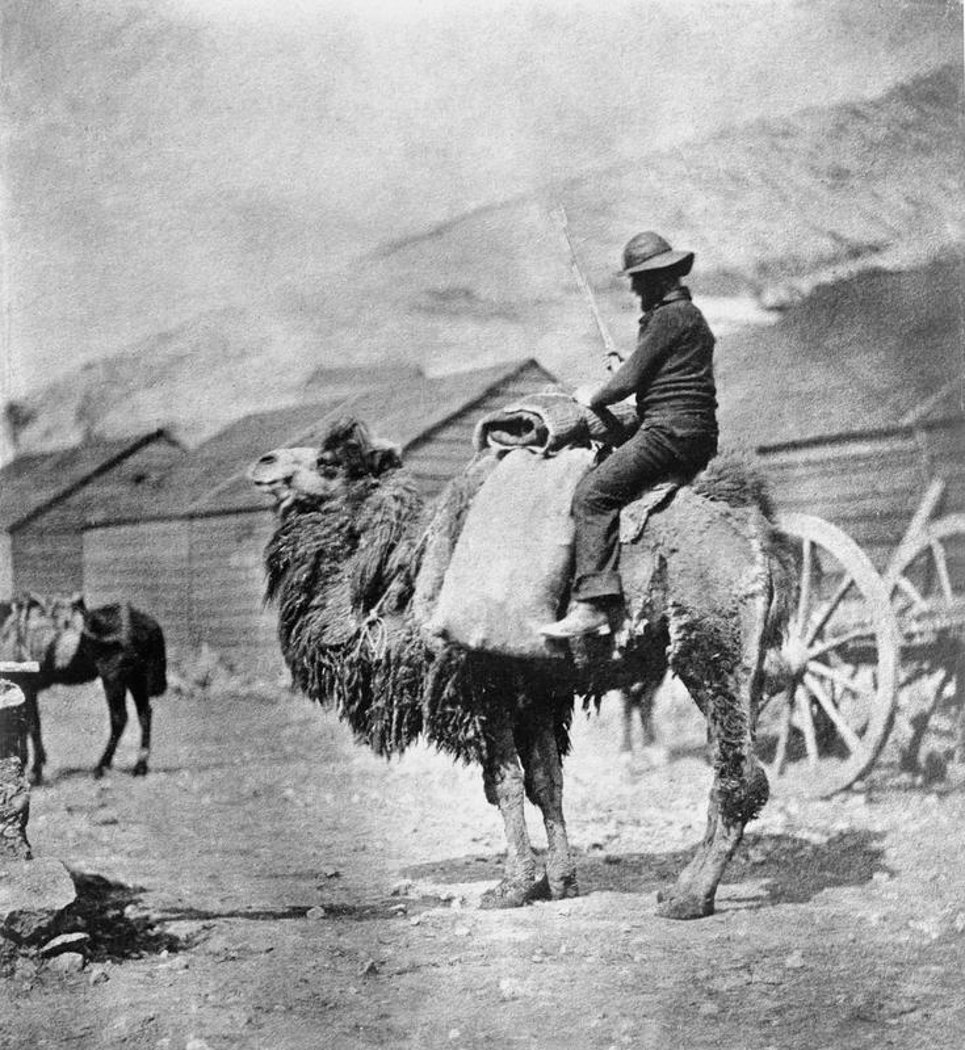

This photo shows a British seaman on a camel at Balaklava, during the Crimean War. The photo was taken by Roger Fenton and is from the Windsor Collection in the Royal Archives. The image is in the public domain.

Florence Nightingale was eager to apply her skills to the challenges in Crimea. She readily accepted Herbert's commission. In November of 1854, she arrived in Crimea. Conditions were wretched when she arrived. Her service in that war-torn theater became legendary. Through dedication, intelligence and hard work, she earned the names Angel of the Crimea and Lady with a Lamp. Her methodology was simple: clean up and pay close attention to the well-being of the sick. In an age before antibiotics, her best allies were cleanliness, fresh air, good food and clean water. These simple innovations proved to be remarkably effective.

This portrait of Florence Nightingale is a classic representation of her as the Lady with the Lamp. The picture is part of a collection at the Wellcome Trust. It is used here under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. Wellcome Trust allows use of its images with proper attribution.

The dreadful conditions in which Florence Nightingale worked took a toll on her. Soon after her arrival in Crimea, she fell ill and ran a high fever for many days. The name given to her affliction at the time was Crimean fever. Considering her symptoms, her environment and her food source, contemporary analysts have suggested her malady may have been Brucellosis. The argument for this is quite strong. Brucellosis was common in Crimea and Miss Nightingale did drink goat milk. Goats, it is understood today, can carry Brucellosis.

Despite a moderately persuasive case for Florence Nightingale having Brucellosis, wild speculations about her malady have been entertained. One psychologist suggested, for example, that Miss Nightingale may have been a manic depressive. This, the psychologist believed, would explain periods of productivity contrasted with periods of inactivity. And then there was the historian F. B. Smith, who suggested Florence Nightingale took to her bed because she simply wanted to avoid work.

It should be kept in mind that when Florence Nightingale was ill, a modern understanding of Germ Theory was still on the horizon.

After she recovered from her acute illness, Florence Nightingale remained in Crimea and devoted herself to the care of soldiers. Upon her return to England in 1856, Miss Nightingale was not her former self. She had relapsing fevers and pain. Her personality, which had never been gentle, became intolerant of company. She took to her bed, and essentially became a recluse.

She, however, did not stop working. From her bed she met people. She consulted with the War Department about reforming medical practices in the field and at home. She helped to inspire the principles of the first Geneva Convention. She promoted the idea of neutrality for the wounded on the battlefield. She wrote a manual on nursing and established a school for nurses. She advanced hospital reform in her book Notes on Hospitals. She did all of this while she was an invalid.

Florence Nightingale in her later years. As the picture suggests, she continued to work throughout her life, though she rarely left home. This picture is from the collection of the Wellcome Trust. It is used under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

A few words about Brucellosis:

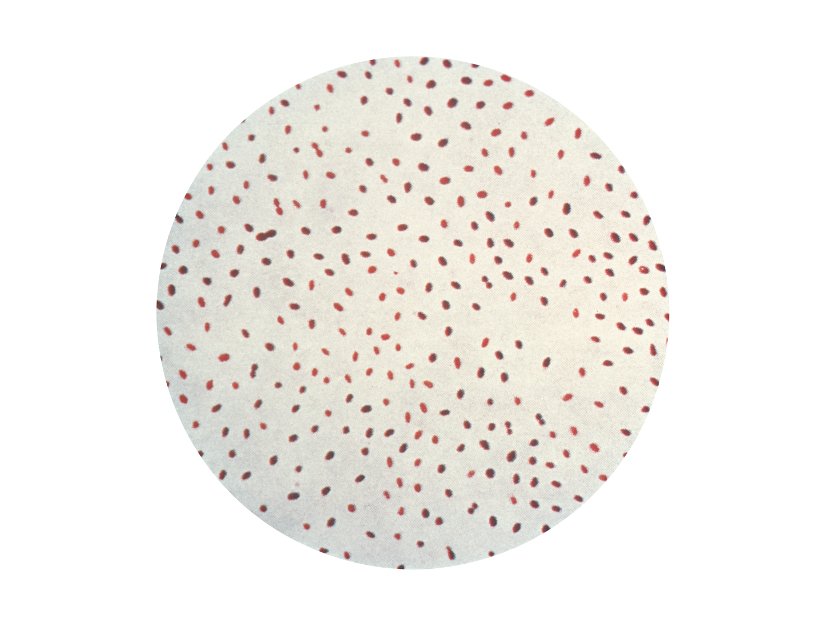

Brucellosis is a zoonotic infection. That is, it is transmitted from animals to humans (although there have been cases of human to human transmission.) There are four different Brucella species: suis, canis, abortus, and melitensis. Human infection most commonly comes from Brucella melitensis.

This picture shows a bison herd in Iowa (U. S. ) where investigative work on a Brucellosis vaccine is taking place. The image is in the public domain because it is credited to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

There is no Brucellosis vaccine for humans, though there are vaccines for sheep, goats and cattle. Treatment for the disease (in humans) entails a long course of antibiotics. Relapse does occur.

One scary note about Brucellosis: because of its potential for airborne transmission, the potential for using this bacterium as a biological weapon has been explored.

A photomicrograph of the bacterium Brucella melitensis. The image is credited to the CDC and is in the public domain.

It is very difficult to diagnose this disease in humans. Symptoms may be pervasive and devastating, or may escape notice. The disease is known by many names--Crimean Fever, Malta Fever, and Bang's Disease are some of the more common. It is believed that the disease may have been around a very long time, perhaps 2,000 years. Some of the organ systems that may be affected are:

The nervous system (meningitis is possible)

Joints (arthritis possible)

Vertebrae (spondylitis possible)

Heart (endocarditis is one of the more fatal complications of the disease)

Gastrointestinal (organs affected may include liver, spleen and pancreas)

This is a partial list of symptoms and gives an idea of how a chronic, unresolved infection with Brucellosis may lead to a lifetime compromised by disease. The symptoms of the disease may wax and wane, which would allow for alternating periods of productivity and illness.

Florence Nightingale changed not just nursing, but medicine, to the benefit of millions. Yes, she did take to her bed, but charging her with hysteria because of this would constitutes wild speculation. The important truth of Miss Nightingale's life is that she devoted herself to service. She was in every sense of the word, a true hero and above the reproach of those who have done far less with their lives.

Some Resources Used in Writing this Blog

https://understandinguncertainty.org/node/204

http://academic.mu.edu/meissnerd/hysteria.htm

https://alumnae.smith.edu/spotlight/shedding-new-light-on-florence-nightingale/

Florence Nightingale: Feminist

Mná Na HÉireann: Women who Shaped Ireland

https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Crimean+fever

https://www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-Balaklava

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/medical-history/article/smithf-b-florence-nightingale-reputation-and-power-london-croom-helm-1982-8vo-pp-216-1295/B6030C8775077A534CAE39C6948766FE)

https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2003/may/4/20030504-113822-4011r/

http://www.antimicrobe.org/h04c.files/history/Brucellosis.asp

http://ocp.hul.harvard.edu/contagion/germtheory.html

https://www.asm.org/index.php/component/content/article/114-unknown/unknown/4469-pasteur-koch-distinctive-ways-of-thinking-about-infectious-diseases

https://archive.org/stream/florencenightin00richgoog/florencenightin00richgoog_djvu.txt

https://ezitis.myzen.co.uk/florencenightingale.html

https://www.biography.com/people/florence-nightingale-9423539

https://www.britannica.com/event/Crimean-War

http://blogs.redcross.org.uk/uk/2010/08/how-florence-nightingale-influenced-the-red-cross/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16964579

http://naturalhealthperspective.com/tutorials/notes-on-nursing.html

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0049388/

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Florence-Nightingale

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27032465

http://www.historiasiglo20.org/pioneers/dunant.htm

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28196298

https://www.infectiousdiseaseadvisor.com/infectious-diseases/brucellosis/article/610198/