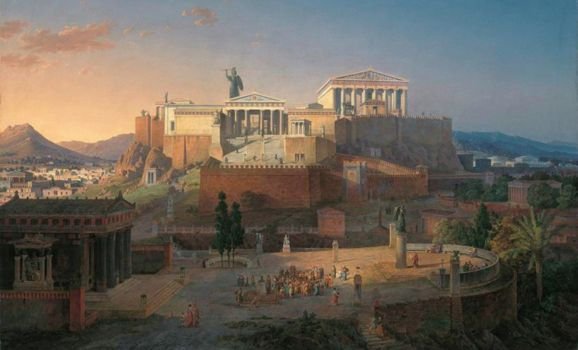

In this series of posts, I share some of the historical and philosophical perspective that will be the foundation of my coming graphic novel about Socrates, Polis: The Trial of Socrates. You can find Part I HERE.

Herodotus, considered by many to be the father of history, wrote in the mid-5th century BCE about Athens' heroics in the great Persian War that took place a generation before he was born. He relates that the Spartans had sent emissaries to their ally Athens in fear that the Athenians would join the vastly superior forces of the Persians. They begged their fellow Greeks to remain true to their homeland and stay in the fight, but the Athenians only took the Spartans' insinuation as an insult. “We know as well as you do that the Persian strength is many times greater than our own... Nevertheless, such is our love of freedom, that we will defend ourselves in whatever way we can.”

Source

In the Histories, Herodotus speaks of freedom or liberty thirty-one times. He considers the value so basic that he even attributes it to the Egyptians of ancient times. Writing of a king he calls Sesostris, Herodotus says that in subjugating the nations in his path, this king respected those peoples who fought valiantly for their freedom and erected pillars in his and their honor; but “if a town fell easily into his hands without a struggle, he made an addition to the inscription on the pillar... he added a picture of a woman's genitals, meaning to show that the people of the town were no braver than women.”

Twice during the Peloponnesian War, in 411 and 404 BCE, the democracy was temporarily toppled and replaced by an oligarchy. In speaking of these brief coups, both Thucydides, the famed historian remembered for his realism and rejection of superstition, and Xenophon, the aristocrat turned mercenary, as well as friend and possible student of Socrates, wrote about the long-standing traditions of freedom and self-rule in Athens. Writing of the oligarchy of 411, Thucydides says: “For it was no easy matter about 100 years after the expulsion of the tyrants to deprive the Athenian people of its liberty – a people not only unused to subjection itself, but, for more than half of this time, accustomed to exercise power over others.”

Source

And Xenophon has Critias, the leader of the Thirty Tyrants who briefly seized power after Athens' defeat by Sparta, say this about Athens: “Not only do we have a larger population than any other Greek city, but the citizens here have been bred up on liberty for far too long.” Not only had Athenian citizens lived by an individualist creed, but they had done so for quite some time.

According to Popper, Western civilization began with the Greeks. They were the first to break free from the chains of tribalism to humanitarianism, or, as we are calling it, individualism. “Individualism, perhaps even more than equalitarianism, was a stronghold in the defenses of the new humanitarian creed. The emancipation of the individual was indeed the great spiritual revolution which had led to the breakdown of tribalism and to the rise of democracy.”

Source

The pinnacle of this spiritual revolution occurred in the generation that lived just before and during the Peloponnesian War, a group of men that Popper calls the “Great Generation”. These included Pericles, the great democratic statesman, and Herodotus, the writer who glorified the democratic credo in his Histories. They included the materialist philosopher Democritus of Abdera, who believed that “every man is a little world of his own” and that the good citizen is he who “considers the whole world his fatherland”; the iconoclastic tragic playwright Euripides, who both questioned the religion of his day and displayed the horrors of war on stage; the skeptical comic playwright Aristophanes who saw no subject so sacred that he could not poke fun at it; sophists like Protagoras who believed that “man is the measure of all things”; and Gorgias who developed the fundamental tenets of anti-slavery and anti-nationalism.

By the end of the 5th century BCE, freedom and self-assertion had become indispensable values to the Greeks, and especially to the Athenians. Men were now glorified not only as tribal heroes but as autonomous, thinking individuals. And just at this peak of tolerance and humanitarianism, Socrates, perhaps the greatest representative of this greatest generation, was killed for his individualism.

The prosecution at Socrates' trial could have used the following words to validate their charge that Socrates was corrupting the youth:

When [a man] is refuted in argument, and when that has happened to him many times and on many different grounds, he is driven to think that there's no difference between honorable and disgraceful, and so on with all other values, like right and good, that he used to revere... when he's lost any respect or feeling for his former beliefs but not yet found the truth, where is he likely to turn? ...And so we shall see him become a rebel instead of a conformer.

No enemy of Socrates could have stated the case against him any better, yet we see these words spring from Socrates' own mouth in Plato's Republic.

Before we can understand this contradiction, we must first examine the sources available that tell of Socrates' life and beliefs. Socrates never wrote anything himself, but there seems to have been a plethora of dialogues written by Socrates' disciples after his trial and execution. Fragments from one of these, written by Antisthenes, have survived, and in the annals of ancient historians can be found ambiguous clues to the existence of many others. But only two authors' works have survived in full into the present day: those of Plato and Xenophon.

Source

The Socrates of Xenophon is hardly a philosopher. He walks about town conversing with his fellow Athenians with a supreme confidence in the knowledge he has accumulated. Rarely do we find in Xenophon the Socratic questioning with which we are so familiar. “Xenophon's Socrates is plainly more interested in conclusions than in the process of reaching them.” (Robin Waterfield) His morality is nothing new or shocking. For the most part, Xenophon's Socrates spouts the aristocratic morality of his day.

His idea of justice, so important in the works of Plato, is the echo of every Athenian citizen: “to do good to one's friends, and do harm to one's enemies.” In Xenophon's Apology, instead of giving moral integrity as his reason for not backing down at his trial, Socrates tells his friends that he is old and that it is better he should die at that moment than to suffer the pains of old age and senility. This, however, is not to say that Xenophon's Socrates lacks charm. In his questioning of the wealthy courtesan Theodote, and in the picturesque drinking party of the Symposium, we find the humorist and ironist we have all grown to love. But the duration and quality of Xenophon's relationship to Socrates is uncertain, and it is clear that he lacks the subtlety of mind, and perhaps the desire, to delve into the depths of philosophy. If we hope to understand the historical Socrates we must look to Plato.

Okay - that's it for Part II. I still don't want to overload you! You can find Part III HERE.

If you found this post interesting and/or useful, I certainly appreciate all upvotes and follows. And I'd love to continue the conversation in the comments below. Thanks for reading

References

- Herodotus. Histories, The. Trans. Aubrey de Selincourt. London: Penguin Books, 1954.

- Plato. Republic, The. Trans. Desmond Lee. London: Penguin Books, 1974.

- Popper, Karl R. The Open Society and Its Enemies Vol. 1 The Spell of Plato. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1962.

- Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War. Trans. Rex Warner. London: Penguin Books, 1954.

- Xenophon. Conversations of Socrates. Trans. Hugh Tredennick. London: Penguin Books, 1990.

- Xenophon. Hellenica. Trans. Rex Warner. Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1966.