This is the final post in a series, where I share some of the historical and philosophical perspective that will be the foundation of my coming graphic novel about Socrates, Polis: The Trial of Socrates. You can find Part I HERE, Part II HERE, and Part III HERE.

Socrates had no political agenda. He was a critic of his democratic government, as the best democrats often are, but he makes it clear by both his actions and his words that he believed Athens was the best government in existence during his lifetime. At his trial, Socrates does not offer exile as a viable penalty for his crimes; when his friend Crito comes to his jail cell to offer escape to another country, Socrates refuses and asks his friend what he would do in Thessaly when he got there, other than eat, “as if I'd exiled myself for a banquet.” Socrates is much more interested in individual morality than politics, and he knows that he knows too little to be developing the perfect government. Richard Kraut, a political and philosophical scholar, sums up what Socrates might have told his disciples had they wished to pursue a career in politics:

If you want to pursue your own best interest, then you must try to become as virtuous as possible. And to do this, you must try to acquire knowledge of the virtues. But the only way to acquire moral knowledge – though of course this is not a method that guarantees success or even progress – is to discuss moral questions every day, as I do. Now, if you enter a political career you will have too little time, or none at all, to care for your own souls... So give up your political ambitions, turn yourselves into moral experts, and then, if you so choose, you can occupy yourselves with politics. Having completed the project of becoming a virtuous person, you can turn to the far less important task...

Source

It is clear that the individual was of supreme importance to Socrates in his search for wisdom, and that the philosopher has a place in that great humanitarian generation of Golden Age Greece. But Socrates goes further than any of his peers. He realizes that there are different levels of freedom. There is freedom from the outward restrictions of the state and from the insatiable desires of the criminal, and these topics were very much in the Athenian air. But there is another freedom which is often overlooked by the most intelligent of people: freedom from false belief and self-deceit. We are, all of us, enchained by the various assumptions and axioms that we have inherited from our families, our cultures, our infirmities. The only way to break free from these chains is to examine everything, from the most basic, to the most sacred.

Source

Karl Popper again:

[Socrates] demanded that individualism should not be merely the dissolution of tribalism, but that the individual should prove worthy of his liberation. This is why he insisted that man is not merely a piece of flesh – a body. There is more in man, a divine spark, reason... It is your reason that makes you human; that enables you to be more than a mere bundle of desires and wishes; that makes you a self-sufficient individual and entitles you to claim that you are an end in yourself.

If Socrates had been the foremost proponent of this individualist humanitarianism, and if Athens had been the most democratic and enlightened city of its age, why did a conflict arise between the two? Before we can answer this question we must first examine the nature of the Athenian democracy.

Athens was an absolute democracy. Every one of the city-state's citizens that could make it to the monthly Assembly meetings had a chance to discuss and vote on all laws and proposals. The idea of free speech was vital to the workings of such a state, and, for the Athenians, such freedom was the essential difference between democracy and tyranny. In his philological investigations, Stone found four words for free speech in the Attic dialect, more than in any language, ancient or modern. And for Euripides, Athens' last great tragic playwright, true liberty is “when free-born men, having to advise the public, may speak free.” But there is one major difference between Athenian freedom and our modern conception of the term. James Colaiaco explains:

Athenian liberties were not founded on what were later called natural rights, existing anterior to the state, but were acquired through active participation in the public realm – the Assembly, law courts, and agora – the realm of speech and reason, discussion and persuasion. The purpose of Athenian law was not to guarantee rights but to preserve the polis.

The Athenians had no Bill of Rights. Freedoms existed because of an absence of restrictive law, and those freedoms could be quashed whenever an individual was thought to be a threat to the polis. Despite numerous advocates to the contrary, the state remained primary to the individual in ancient Athens.

Source

The charges levied against Socrates were vague, but they came down to two crimes: impiety and corruption of the youth. To our modern ears, the existence of such crimes sounds like blasphemy against our most sacred democratic values; but to the men of 5th century BCE Athens, such acts were considered treason against the state. Even so, why did they go after Socrates at this particular time? Nothing about Socrates' actions or lifestyle had changed: he still walked the agora every day, drawing crowds with his debates and examinations of others; he still questioned the legitimacy of the flawed, Homeric conception of the gods, though he dutifully continued to make the proper daily sacrifices. At age seventy, with not much life left to live, why did Socrates' prosecutors bother to take the philosopher to trial after so much time? To understand this, we must place Socrates' trial in its proper historical context.

By 399 BCE, Athens had endured and lost a pan-Hellenic war that lasted some thirty years. Within ten years of Socrates' execution, Athens had endured three violent revolutions, events Stone calls “political earthquakes”, that shook the city's security and created in its citizens a tremendous feeling of anxiety. The first was an oligarchic revolution of four hundred men that lasted four months in 411; the second was the Spartan puppet-government of the Thirty Tyrants that lasted eight months in 404 at the end of the Peloponnesian War. While brief, each of these coups turned into a bloodbath as both sides, the democrats and the oligarchs, sought to get and keep the upper hand. The third “earthquake” occurred in 401 when the remnants of the oligarchic movement tried and failed to topple the democracy for a third time. By the time of Socrates' trial, the democratic government had regained its strength, but its citizens were still fearful of any threat against their security and their traditions.

Critias condemns Theramenes

Athens had witnessed the corrosion of its values by violence, plague, and revolution, and the average citizen was not about to sit by and watch as Socrates sowed the seeds of future instability with his reckless teachings. Many people around him saw Socrates' questioning of traditional values as destructive when he failed to offer any positive doctrine to take their place. Even Callicles, Plato's representative of hedonism and realpolitik in the Gorgias, is taken aback by Socrates' views: “If you are in earnest and what you say is really true, our human life would be turned upside down. We would be doing exactly the opposite, it seems, of what we should.” The Athenian citizens simply wanted peace. They wished to be left alone to go about their daily activities; they wanted to enjoy their festivals and make the sacrifices to their gods that their forefathers had made before them. But more than anything, the Athenians wanted a rest from the critical thinking that Socrates and the Great Generation had thrust upon them – a questioning of values that many thought had led to the fall of their city. But Socrates refused to grant them their wish. This is how he describes himself to the jurors at his trial:

[I am] a man who – if I may put it a bit absurdly – has been fastened as it were to the City by the God as, so to speak, to a large and well-bred horse, a horse grown sluggish because of its size and in need of being roused by a kind of gadfly. Just so, I think, the God has fastened me to the City. I rouse you. I persuade you. I upbraid you. I never stop lighting on each one of you, everywhere, all day long.

When Socrates placed his search for truth and self-discovery above the traditions and values of his city, he became a threat to the safety and sanity of his peers. And the Athenians, not wishing to be roused from their slumber, swished the city's collective tail and crushed the gadfly underfoot.

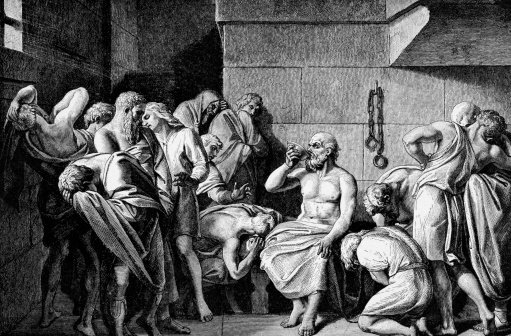

Socrates' Execution

The trial and execution of Socrates is one of history's most tragic episodes, and it is a tremendous black mark on the legacy of an otherwise great city. It is hard to read Plato's Apology or Phaedo without brushing a few tears from one's eyes. Solon, the great Athenian lawmaker of the 6th century BCE, said, “Look to the end no matter what it is you are considering. Often enough God gives a man a glimpse of happiness, and then utterly ruins him.” But if we look at Socrates in his final living hours, we see all the markings of a happy man: he was surrounded by friends and family; revered for his honesty and integrity; confident in his never committing an unjust act against another. His students and disciples wrote about him and his beliefs for years after his death, and 2400 years later, the name Socrates is still a rallying cry that inspires heroic individualism and uncompromising integrity. In conclusion, let us leave with these parting words from Gregory Vlastos, where he describes how this happiness is possible, not only to Socrates, but to every man who pursues that same vision of truth and integrity:

If you say that virtue matters more for your own happiness than does everything else put together, if this is what you say and what you mean – it is for real, not just talk – what is there to be wondered at if the loss of everything else for virtue's sake leaves you light-hearted, cheerful? If you believe what Socrates does, you hold the secret of your happiness in your own hands. Nothing the world can do to you can make you unhappy.

Source

That concludes my mini-series on Socrates and Indvidualism. If you found this post interesting and/or useful, I certainly appreciate all upvotes and follows. And I'd love to continue the conversation in the comments below. Thanks for reading!

References

- Colaiaco, James A. Socrates Against Athens. New York: Routledge, 2001.

- Kraut, Richard. Socrates and the State. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984.

- Plato. Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Meno, Gorgias, Menexenus. Trans. R.E. Allen. New Haven and London: Harvard University Press, 1984.

- Popper, Karl R. The Open Society and Its Enemies Vol. 1 The Spell of Plato. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1962.

- Stone, I.F. The Trial of Socrates. New York: Anchor Books, 1989.

- Vlastos, Gregory. Socrates: Ironist and Moral Philosopher. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991.