This is the second part of our four part series on Rhetoric and Music. Part 1 is here, Part 2 is here, Part 3 is here and Part 4 is here.

Music from the Middle Ages and Renaissance

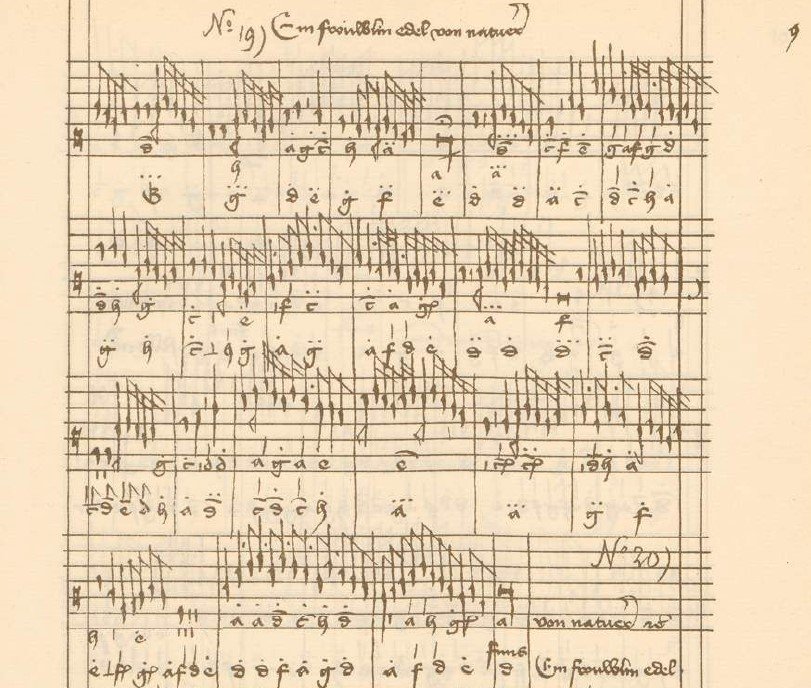

Extract from the song "Ein fröuwlin noble von natuer". Sourced from the Buxheimer Organ Book (around 1460/70 in tablature notation)

Throughout most of its history European music was mostly vocal music. Musicians were traditionally trained according to the rhetorical principles that applied to the production of written texts. Poets were at the same time also singers who wrote or improvised melodies for their texts themselves and accompanied themselves on liras, lutes or harps during the presentation. In the Renaissance, arrangements and adaptations of vocal music were the largest part of recorded (written) music for instruments (see image above).

In the Middle Ages, rhetoric was one of the seven liberal arts, the seven branches of science in the universities. To be precise, it was part of the Trivium, the three basic subjects, consisting of grammar, rhetoric and dialectica. After three years of following these basic subjects, the student was named baccalaureous and ready for the four-year Quadrivium. This included arithmetic, geometria, musica and astronomia. After successful completion of the Trivium, he was also suitable for spiritual or official functions. The medieval music theorists and composers thus knew the works of antique rhetoricians. Some of graduates invoked the ancient officia oratoris, they recognized the rhetorical principles in the texts and began to structure the music according to the texts. They developed a sense of musical style that matched the content of the text.

This development continued during the Renaissance. From the second half of the 15th century, the composers Josquin Desprez, Alexander Agricola and some other contemporaries began to use musical figures that were inspired by the text or by certain important words. In this way, they wanted to represent the affects of the texts. They also began to record the text distribution precisely, which was often not the case before.

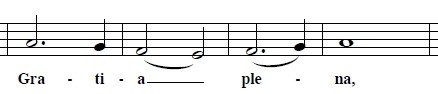

In his motet "Ave Maria, virgo serena", Josquin is inspired by the words to the rhythms and melodies. For the word Gratia he uses a dotted rhythm, similar to the rhythm of the spoken word:

Extract from Josquin, Ave Maria

And he uses musical figures to represent the words:

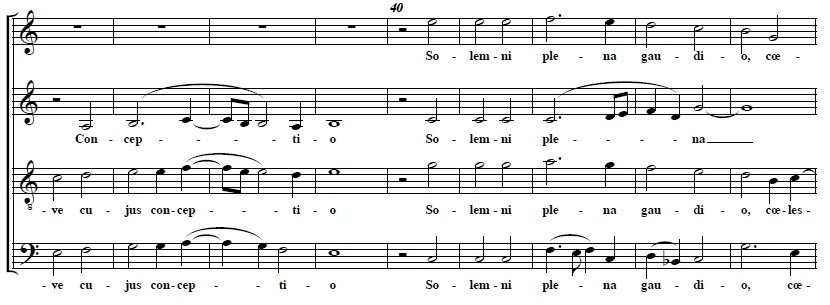

To represent the words "Solemni plena gaudio" (full of festive joy), Josquin composes them in a full, four-part setting (homophony, size 40). Because the text is only two and three voiced and polyphonic in composition, it is clear:

Extract from Josquin, Ave Maria

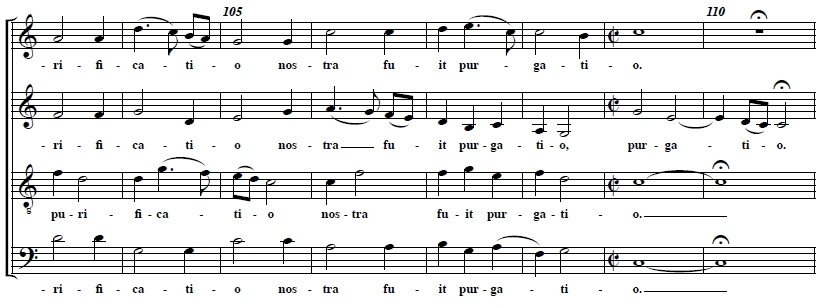

In the" Cuius Purificatio Nostra fuit purgatio" (whose purification was our cleansing), the soprano, tenor and bass in size 110 finish on the same note, the c (unisonus). This one clean note symbolizes the cleansing. Because the alto voice reaches the c one and a half measure later, the text is particularly well represented and the cleaning is acoustically very perceptible:

Extract from Josquin, Ave Maria

The influence of Josquin on the next generations of composers was immense. During the 16th century, composers continued to develop musical settings or figures with which they could better express texts and affects. This caused more dissonances and resolutions that violated the strict rules of the counterpoint. This was especially the case in Madrigals with their expressive texts.

Theorists therefore criticized the madrigalists, a well-known example is the criticism of Giovanni Artusi about some madrigals of Monteverdi (see Giovanni Maria Artusi: L'Artusi, ovvero delle imperfettioni della moderna musica, Venice 1600). In the preface of his Scherzi musicali, he stated that the word is the author of music (harmonia) and not the servant. This was the difference between the strict 16th-century Prima pratica (Palestrina, Zarlino) and the Stile moderno or Seconda pratica invented by Monteverdi. Monteverdi wanted to compose the text not only in a declamatorically correct way, but also to observe the emphasis and the length of the syllables of the words. He also wanted to make clear the affect of the text for the public. For him, this goal was the justification for breaking old strict rules through the use of dissonant harmonies and their (correct) solutions. These and the previously described settings (Josquin) were called "Figures" by German theorists.

Musica Poetica

Figures are not melodies by themselves, figures arise when filling intervals through intermediate tones that do not belong to the harmony (or chord) in question (transitus), thus all figures can be explained by the harmony. The number of figures or dissonances that were used was also important. Man was seen to be the image of God, he was built to the same perfect relationships as the universe and the earth, moving according to a divine plan (Musica universalis). The harmony in music works according to the same principles. Each dissonance brings this balance into imbalance and affects the listener. The imbalance must be corrected correctly. German theorists tried to explain how these dissonances arise and how they are solved in a correct way. They labelled both settings with dissonances and settings that differed from the standard figures. And they named them after figures from the rhetoric because they often saw parallels between the two disciplines. They named Musica Poetica the so-called composition theory. In this case, the word "poetica" does not mean poetry but the poiesis, the achievement of the musical goal, namely to move. In their treatises, they made harmonic analysis of existing compositions. They also assigned certain musical means to certain affects. The theory of affects and composition were closely linked. The purpose of the treatises was that composers learned to compose music that "touches the hearts and souls to bring them into different moods".

Musica poetica spread rapidly among musicians and composers, especially in German-speaking areas. An important reason for this was that Musica Poetica was an important part of the curriculum at the Lutheran Latin schools. Unlike the Catholic Church and other Reformers such as Calvin or Zwingli, Luther saw in the art of music "besides the word of God the greatest treasure on earth". According to him, music was a gift from God, it was not a human gift. For him, music was the sister of theology who, through her power to touch the listener, was ideally suited to proclaim the word and to praise God. Sung text was much better remembered than read text. That is why Luther thought that every teacher and pastor should be able to sing. Every church composer should help to proclaim the word of God and to positively influence the development of man. The Practice of composition was an important tool for teaching them that.

The first important treatises were written by Joachim Burmeister (including Musica Poetica, 1606), Johannes Nucius (Musices Poeticae, 1613) and Athanasius Kircher (Musurgia universalis, 1650). The analysis of "In me transierunt" by Orlando di Lasso by Burmeister is the first known analysis of a piece of music.

Going back to Aristotle, one began to distinguish between Musica theoretica, Musica practica and Musica poetica:

- Musicus Theoreticus: "who only has the science [of music], and at least can discuss and speak about it"

- Musicus Practicus: "who practices and performs the music"

- Musicus Poeticus (composer): "who can not sing alone but who also manages to produce his own opus or work [...]"

(Johann Andreas Herbst: Musica Poëtica, Nürnberg 1643)

The only author of a composition theory who was also an important composer was Christoph Bernhard. His handwritten Tractatus Compositionis Augmentatus is based on the teachings of his master Heinrich Schütz (1585-1672). In this Tractatus he writes: "A figure is a certain way to use a dissonance, so that it is not only disgusting, but pleasant, and in that way reveals the skills of the composer." With this he connects directly with Monteverdi's Stile moderno. Bernhard's treatise circulated well into the 18th century.

Jörn Boysen

Running an ensemble is a rewarding but time consuming job. Chasing after grants and sponsorship is the often overlooked but important aspect of a musician's life. If our post has passed the reward period, please consider a donation or a delegation. We also accept tokens of support at the following addresses:

BTC

1Mwe6XaDcREa7o5RSLGoWfk9wSwGs6LkSA

LTC

LPcEtTsxMJykDeK713jsj3e2BsdVf32ix7

ETH

0x1bb1d830f66bdb74de45685a851c42b790587a52

Doge

DMJNS7jbNCgPdFdxgeFdEummFMmSQvAoK2

Musicoin

0x9c1fc741f0869115f8c683dc6967131ab1c40ebc

Smartcash tips accepted!

Our Musicoin artist page

Thanks for you support!

The classical music community at #classical-music and Discord.

Follow our community accounts @classical-music and @classical-radio.

Follow our curation trail (classical-radio) at SteemAuto

Community Logo by ivan.atman

.png)