- How Old Is Newgrange? (Part 1)

A Simple Question

Newgrange is the Jewel in the Crown of Irish archaeology, and is commonly regarded as Ireland’s national monument. It dominates the UNESCO World Heritage Site known officially as Brú na Bóinne – Archaeological Ensemble of the Bend of the Boyne. Irish archaeologists never tire of reminding us that it was constructed by Neolithic farmers more than 600 years before the Great Pyramid of Giza. Irish astronomers bask in the glory of what is arguably the world’s oldest astronomically aligned monument.

But is all this national pride truly justified? How old, in fact, is Newgrange? A simple question. But finding the correct answer to this question is by no means a simple task.

A Simple Answer

In the 1970s, when radiocarbon dates were calibrated with the help of dendrochronology, or tree-ring dating, archaeologists finally reached a consensus on this important issue—a consensus which the past forty years have done nothing to erode:

Newgrange was built towards the end of the fourth millennium BC. The burnt soil, used to caulk the reef joints of the tomb, contained charcoal fragments which provided radiocarbon date ranges of 3316–2922 BC and 3304–2922 BC which probably date the construction of the tomb. (Waddell 62)

But is this the correct answer to our simple question? If radiocarbon dating and dendrochronology are shown to be untrustworthy, are the archaeologists left with a leg to stand on? As we shall presently see, before these methods of absolute chronology were introduced, the range of dates assigned to Newgrange by the experts was very different from the range given above by Waddell.

The Discovery of Newgrange

How does one lose a building as large and as imposing as Newgrange? How does an entire nation mislay a national monument which sits on a ridge overlooking the Boyne Valley and is visible for miles around? But that is precisely what happened sometime in the Middle Ages. Newgrange was sealed, abandoned and forgotten.

In 1699, when the estate of New Grange in County Meath was leased for ninety-nine years to a Williamite settler named Charles Campbell, the existence of the now-famous passage grave was unknown. It was when Campbell’s workmen were quarrying stones from the overgrown mound to repair a nearby road that they discovered what appeared to be the mouth of a cave.

Shortly thereafter the Welsh antiquary Edward Lhwyd visited Newgrange and examined the mound. Unfortunately his fieldnotes were subsequently lost in a fire at a London bookbinder’s, but his correspondence from this period has survived, and a number of his letters refer to the discovery—or, rather, rediscovery—of this lost treasure. The following was addressed to the English physician and naturalist Tancred Robinson a few months later:

We continued not above 3 days at Dublin, when we steered our course towards the Giants Causway. The most remarkable Curiosity we saw by the way, was a stately Mount at a place called New Grange near Drogheda: having a number of huge Stones pitched on end round about it, and a single one on the Top. The Gentleman of the Village (one Mr Charles Campbel) observing that under the green Turf this Mount was wholly composed of Stones, and having occasion for some, employed his Servants to carry off a considerable parcel of them; ’till they came at last to a very broad flat Stone, rudely carved, and placed edgewise at the bottom of the Mount. This they discovered to be the Door of a Cave, which had a long Entry leading into it. At the first entering we were forced to creep; but still as we went on, the Pillars on each side of us were higher and higher; and coming into the Cave we found it about 20 foot high. In this Cave, on each hand of us was a Cell or Apartment, and an other went on, streight forward opposite to the Entry. In those on each hand was a very broad shallow Bason of Stone, situated at the Edge. The Bason in the right hand Apartment stood in another: that on the left hand was single; and in the Apartment streight forward there was none at all. We observed that water dropt into the right hand Bason, tho’ it had rained but litle in many days; and suspected that the lower Bason was intended to preserve the superfluous Liquor of the upper, (whether this Water were sacred, or whether it was for Bloud in sacrifice) that none might come to the Ground. The Great Pillars round this Cave supporting the Mount were not at all hewn or wrought but were such rude Stones as those of Abury in Wiltshire, and rather more rude than those of Stonehenge; but those about the Basons, and some elsewhere, had such barbarous Sculpture (viz. Spiral like a Snake, but without distinction of head and tayl) as the forementioned Stone at the Entry of the Cave; There was no flagging nor floor to this entry nor cave; but any sort of loose stones every where under feet.

They found several Bones in the Cave, and part of a Stags (or else Elks) head; and some other things, which I omit, because the Labourers differed in their Account of them. A Gold Coyn of the Emperour Valentinian, being found near the top of this Mount, might bespeak it Roman; but that the rude Carving at the Entry and in the Cave seems to denote it a barbarous Monument. So the Coyn proving it ancienter than any Invasion of the Ost-mans or Danes, and the Carving and rude sculpture, barbarous; it should follow, that it was some place of Sacrifice or Burial of the Ancient Irish. (Lhwyd 15 December 1699)

In January of 1700, Lhwyd wrote the following account to Thomas Molyneux of the Dublin Philosophical Society:

But to give you some Account of our Journey one of the most Remarkable Occurrences in our way hither from Dublin was a large Tumulus or Barrow at a Village calld new Grange within four Miles of Drogheda. It has on the Top a Stone pitchd on End and others Vastly large, pitchd round about it; at Bottom; within it is a Cave, the Entry whereof is guarded on each side with large rude Stones standing on End, having somtimes a Barbarous Sculpture on ’em not unlike the Ruin Monuments in Wormius’s Monumenta Danica and on the Top of these are other Stones laid acrosse but no Letters at all. At the first Entry these supporters are so pressd with the Weight of the Hill and the Top Stones are so that they that goe in must Creep but by Degrees ’tis still higher till you goe into the Cave, which may be about 6 or 7 Yards in Height. Having enterd the Cave you have on each Hand a Cell or Apartment and another streight forward. In the right hand Cell there is on the Ground a very large Stone Bason or Cistern and within that another with its Brim odly scituated and some very Clear water within it; dropt from the roof of the Cave, tho but an Artificial Mount of Stones. On the left hand there is a Single Bason with the same Sort of Brim, but we found no Water in’t. The floor of this Cave is nothing but a smaller loose Stones, amongst which were found great Quantity of Bones, Staggs horns, and as they said a peice of an Elkshorn, peices of Glass and some kinde of Beads. Near the top of this Mount they found a gold Coyn, which Mr Campbell the Proprietor of this Village shew’d me and tis a Coyn of the Emperor Valentinian. However not withstanding this Coyn, I cannot think this Mount a Work of the Romans in regard the Carving of the Stones is plainly Barbarous and the whole Contrivance too rude for so polite a people. I should have been very apt to Conclude it Danish, but the Date of the Coyn is several Centuarys older than their first coming into Ireland, which (as far as the Irish Annalls Informe us) was about the year 800. Thus being neither Roman or Danish it remains it should be a place for sacrafice us’d by the Old Irish, and Mr Cormuck Oneil told me they had a vulger Legend about some Strange Operation at that Town in the time of Heathenisme which I shall endeavour to get from him more particularly.

About three months later, Lhwyd wrote in a similar vein about the discovery to a fellow Welsh antiquary, Henry Rowlands:

I also met with one monument in this kingdom very singular: it stands at a place called New-Grange near Drogheda; and is a Mount or Barrow of very considerable height encompass’d with vast stones pitch’d on end round the bottom of it; and having another lesser standing on the top. This Mount is all the work of hands, and consists almost wholly of stones, but is cover’d with gravel and greenswerd, and has within it a remarkable cave. The entry into this cave is at bottom, and before it we found a great flat stone, like a large tomb-stone, placed edgwise, having on the outside certain barbarous carvings, like snakes encircled, but without heads. This entry was guarded all along on each side with such rude stones pitch’d on end, some of them having the same carving, and other vast ones laid a-cross these at top. The out pillars were so close press’d by the weight of the Mount, that they admitted but just creeping in, but by degrees the passage grew wider and higher till we came to the cave, which was about five or six yards height. The cave consists of three cells or apartments, one on each hand and the third straight forward, and may be about seven yards over each way. In the right hand cell stands a great bason of an irregular oval figure of one entire stone, having its brim odly sinuated or elbow’d in and out; and that bason in another of much the same form. Within this bason was some very clear water which drop’d from the cave above, which made me imagine the use of this bason was for receiving such water, and that the use of the lower was to receive the water of the upper bason when full, for some sacred use, and therefore not to be spill’d. In the left apartment there was such another bason, but single, neither was there any water in it. In the apartment straight forward there was no bason at all. Many of the pillars about the right hand basons were carvd as the stones above-mentiond; but under feet there were nothing but loose stones of any size in confusion; and amongst them a great many bones of beasts and some pieces of deers horns. Near the top of this Mount they found a gold coin of the Emperor Valentinian; but notwithstanding this, the rude carving abovemention’d makes me conclude this monument was never Roman, not to mention that we want History to prove that ever the Romans were at all in

Ireland. (Lhwyd 12 March 1700 [Gregorian])

Finally, on 7 May 1700, Lhwyd mentioned Newgrange briefly in a second letter to Thomas Molyneux:

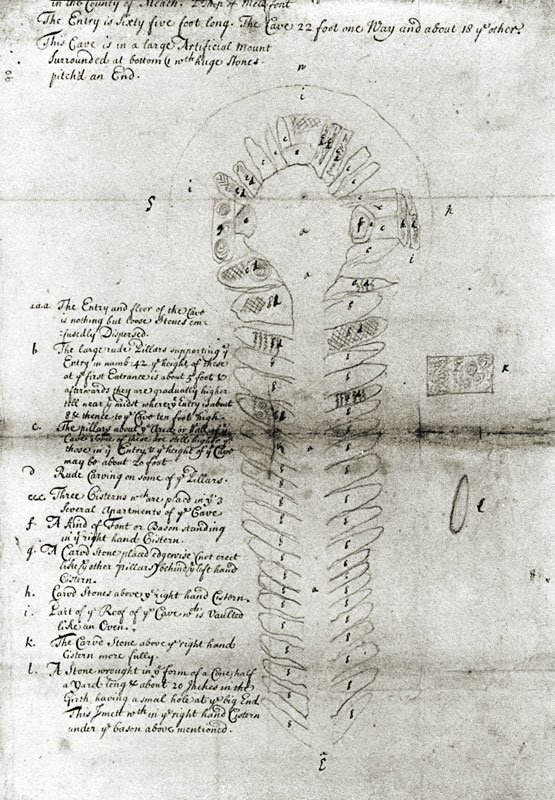

Will Jones gives you his humble Respects and sends you a Draught of the Cave at New Grange.

William Jones was Lhwyd’s draughtsman and his Draught of the Cave at New Grange is the earliest surviving plan of the monument. Lhwyd also sent a copy of Jones’s draught to the English antiquarian John Anstis:

On 12 March 1708 the Irish historian Roderic O’Flaherty wrote to Lhwyd in response to some of the latter’s queries:

I writ a 100. annotations in answer of their Queryes, but sent them none as yet. Among the rest I found out the cave, whence one was expelled by Druid enchantments whereof you writ to me by the relation of one Mr O Neill. The cave is Bruġ na Boinne, which you saw, as I saw the description thereof with you: out of which Elcmar an Broġa (Ogy: p: 181: lin: 2) turn’d out Ængus an Ḃroġa by magick art: both of ’em so surnam’d from Bruġ na Boinde: where King Dagda (Ogygiæ p: 179 lin: 1) the said Ængus’s father after 80 y(ears) reign gave up the ghost.

O’Flaherty is best known today as the author of an elaborate history of Ireland, Ogygia. He was, it seems, the first scholar to identify Newgrange with Brugh na Bóinne (The Mansion on the Boyne), a divine dwelling place that is mentioned in a number of Irish myths and legends. O’Flaherty accepted these stories as historical accounts.

The origins of the name New Grange may be traced back to 1142, when the Cistercian Monks founded the monastery of Mellifont Abbey in County Louth. Many outlying farms—or granges—were subsequently incorporated into the holdings of the abbey. New Grange is not listed among the abbey’s granges in the earliest charters of the 12th and 13th centuries, but the Inspeximus granted by Edward III in 1348 includes a Nova Grangia (New Grange) among the abbey’s demesne lands (in grangiis suis) in the counties of Meath and Louth (in Comitatu Midie et Urielis). (Colmcille 5, 8)

On 23 July 1539, following the Dissolution of the Monasteries by Henry VIII, Mellifont Abbey became the fortified mansion of an English soldier of fortune Edward Moore, ancestor of the Earls of Drogheda (Stout 85, 102). On 14 August 1699, Alice Moore, Countess Dowager of Drogheda, leased the demesne of Newgrange to a Scottish settler, Charles Campbell, for 99 years (Stout 128).

It is often claimed that Newgrange was one of the many estates confiscated by William III after the Battle of the Boyne. While it is true that the estates of landowners who had supported James II were confiscated and subsequently deeded to loyal Williamite settlers like Charles Campbell, Newgrange was not one of them. The Moores had fought for William III in the Williamite Wars, and the 3rd Earl of Drogheda Henry Hamilton-Moore was even appointed Commissioner for Forfeited Estates in 1699. Campbell came into possession of Newgrange when Henry’s mother, Alice Moore, leased it to him.

It is still sometimes asserted that the Irish name Brugh na Bóinne actually refers to the entire Boyne-Valley complex of ancient tombs, including Knowth and Dowth, while Newgrange itself was known as Síodh an Bhrugh (The Fairy Mound of the Brugh). As we shall see later, William Wilde, the father of Oscar Wilde, was largely responsible for this interpretation of Brugh na Bóinne as Region of the Boyne (Dinneen 130: bruġ). This is probably an error. James O’Laverty’s testimony, which we shall also have occasion to examine later, leaves little doubt that Newgrange was the Brugh. T F O’Rahilly has a less than literal understanding of the term síodh (or síd):

Bruig na Bóinne was a famous pagan burial-ground on the north bank of the Boyne, to the east of Slane. In it was a síd or Otherworld location. (O’Rahilly 516 fn 1)

Taking Stock

These early exchanges between Lhwyd and his colleagues established the working hypothesis that Newgrange was the Brugh na Bóinne of Irish literary tradition and that it was a place of Sacrifice or Burial constructed by the Ancient Irish or the Old Irish no later than the time of Valentinian I (364-375 CE). Lhwyd was prepared to accept that the structure was of Danish appearance, but the discovery of a coin from the time of Valentinian convinced him that it must predate the Scandinavian Era, which began in 795 CE with the sacking of Rechru. However, he never attempted to establish a terminus post quem—or earliest date—for the construction of the monument. How ancient were Lhwyd’s Ancient Irish? How old were his Old Irish? These are questions he left for posterity to ponder over and perhaps, in time, to answer.

To be continued ...

References

- Father Colmcille, An Important Mellifont Document, Journal of the County Louth Archaeological Society, Volume 14, Number 1 (1957), pp 1-13

- Patrick S Dinneen, An Irish-English Dictionary, Irish Texts Society (1927), Elo Press Ltd, Dublin (1996)

- Edward Lhwyd, Letters, 15 December 1699, To Tancred Robinson

- Edward Lhwyd, Letters, 29 January 1700 (Gregorian)

- Edward Lhwyd, Letters, 12 March 1700 (Gregorian), To Henry Rowlands

- Edward Lhwyd, Letters, 7 May 1700

- T F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute of Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946)

- Geraldine Stout, Newgrange and the Bend of the Boyne, Cork University Press, Cork (2002)

- John Waddell, The Prehistoric Archaeology of Ireland, Wordwell Ltd, Bray, County Wicklow (2000)

Image Credits

- Newgrange: Wikimedia Commons, Shira, GNU Free Documentation License

- edward Lhwyd: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

- Thomas Molyneux: Roubiliac (sculptor), Armagh Cathedral, Timothy Belmont (photographer)

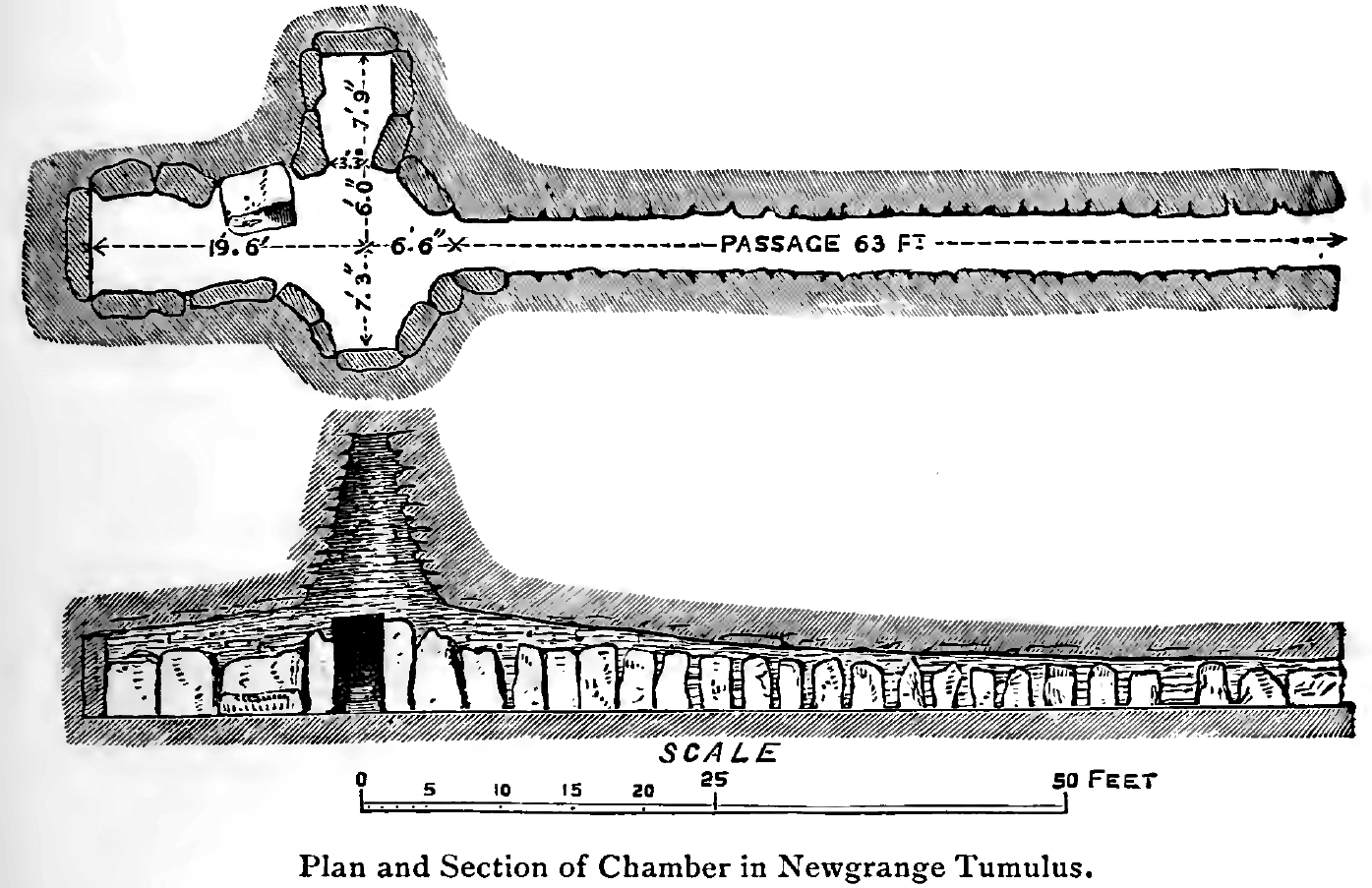

- Plan and Section of Chamber in Newgrange Tumulus: Wikimedia Commons, William Frederick Wakeman, Public Domain

- Will Jones’s Draught of Newgrange: Trinity College Dublin, William Jones, Public Domain