Posts in this series: Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3 / Part 4 / Part 5

When I had the crazy idea to learn Japanese in 2007, I was convinced that it wouldn’t be possible for me. A couple things made this undertaking feasible and I’d like to talk about what worked best. Most of what I recommend will be free or cheap, so it’s okay if you don’t have money for a college course or something similar.

This post isn’t “One Surprising and Super Secret Way to Learn a Language!” It will take a ton of motivation and dedication to reach fluency, but it is absolutely possible for anyone who puts in the time.

The game changer for me was discovering All Japanese All The Time. The two main concepts from this site that changed my way of thinking about learning languages are:

1. A spaced repetition system (SRS) called Anki

2. The input hypothesis, and learning through fun things like watching TV, listening to podcasts, and reading books/comics

I’ll talk about these below, as well as walk you through the rest of the steps that I took to get to my current level of fluency.

Disclaimer: I would say the highest level of proficiency I’ve reached is in the upper intermediate range (something like B2 on the CEFR scale). I passed the highest (N1) level of the Japanese-Language Proficiency Test (JLPT) in 2012, am able to understand enough of the language to enjoy TV and comics without a dictionary, and can comfortably have conversations with native speakers.

In case you want to seek out advice from people who have reached a very advanced level, here are some of the people who have really been inspiring for me. They are true masters!

- Dogen / twitter / youtube / patreon

- Matt vs. Japan / twitter / youtube / patreon

- Japanese Level Up / website / twitter

Comprehensible Input

The general idea behind most of the study methods I’ll talk about stem from the idea of “comprehensible input,” which is the idea that while learning a language, the only thing that can improve your linguistic competence is input you can understand.

It might seem counter-intuitive at first to focus on input (like books, movies, etc.) instead of speaking, but it makes sense if you think about it. Our goal is to get all of the words and phrases into your head, and extensive exposure to Japanese will give you an intuitive sense for what feels right. Speaking practice will help bring things full circle, but it won't be the main focus. Speaking the language without knowing it well enough can actually solidify errors that are really hard to correct later on.

Check out the articles on Antimoon for more info about these ideas. Their site is written for people learning English, but the explanations are still really helpful.

Where do I start?

First, let’s take a quick look at the parts of Japanese we’ll need to learn. The main ones are:

- writing system

- grammar / words / sentences

- input (reading, TV, podcasts, etc.)

- output (speaking, writing)

- advanced concepts (going monolingual, pitch accent)

I’ll take a look at each of these in the sections that follow.

The Writing System

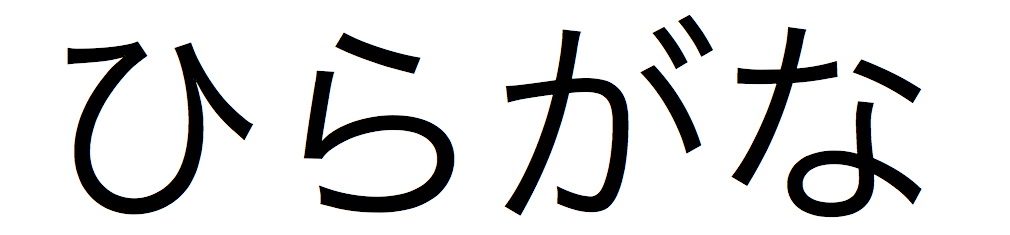

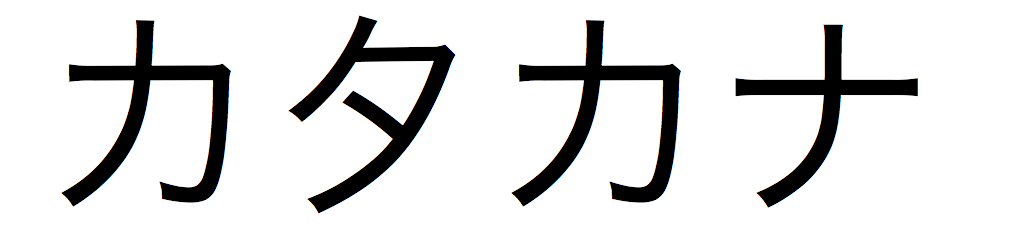

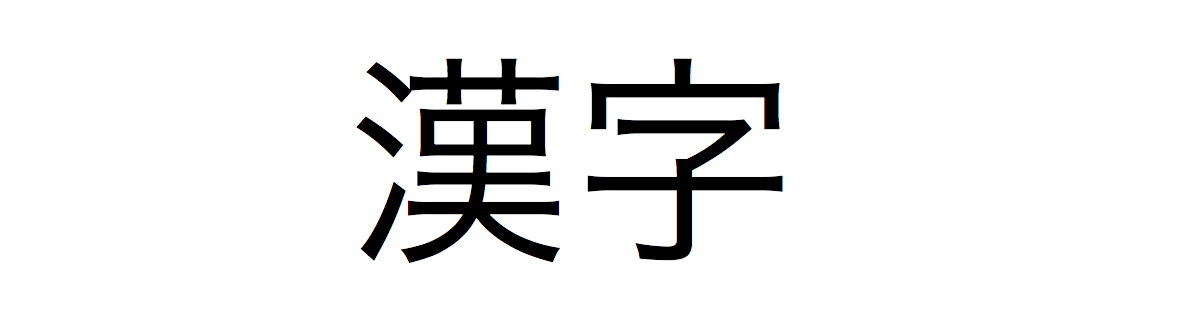

Japanese uses three writing systems: hiragana, katakana, and kanji.

Hiragana is phonetic (each character corresponds to a specific sound). So you can read it just like you can read English. It looks like this:

Katakana is also phonetic, but it is mainly used for loan words. It looks like this:

Kanji are the scariest ones. They’re the more complicated characters that are originally from the Chinese language. They look like this:

When it comes to learning to read, kanji will be what makes our lives much more difficult. We’ll need to be familiar with a couple thousand of them to read Japanese. This is where an SRS comes in.

Anki (Spaced Repetition System)

Anki is a spaced repetition system (SRS). You create digital flash cards in it (or download pre-made decks) and then study them in the application on your computer or phone. This will be the main SRS I talk about in this guide, but there are several other popular ones out there now, including Memrise, which is more user friendly but not as customizable. I’ll talk about Anki because it’s the one I have the most experience with and it’s customizable enough to allow us to study in a certain way.

An Example Card

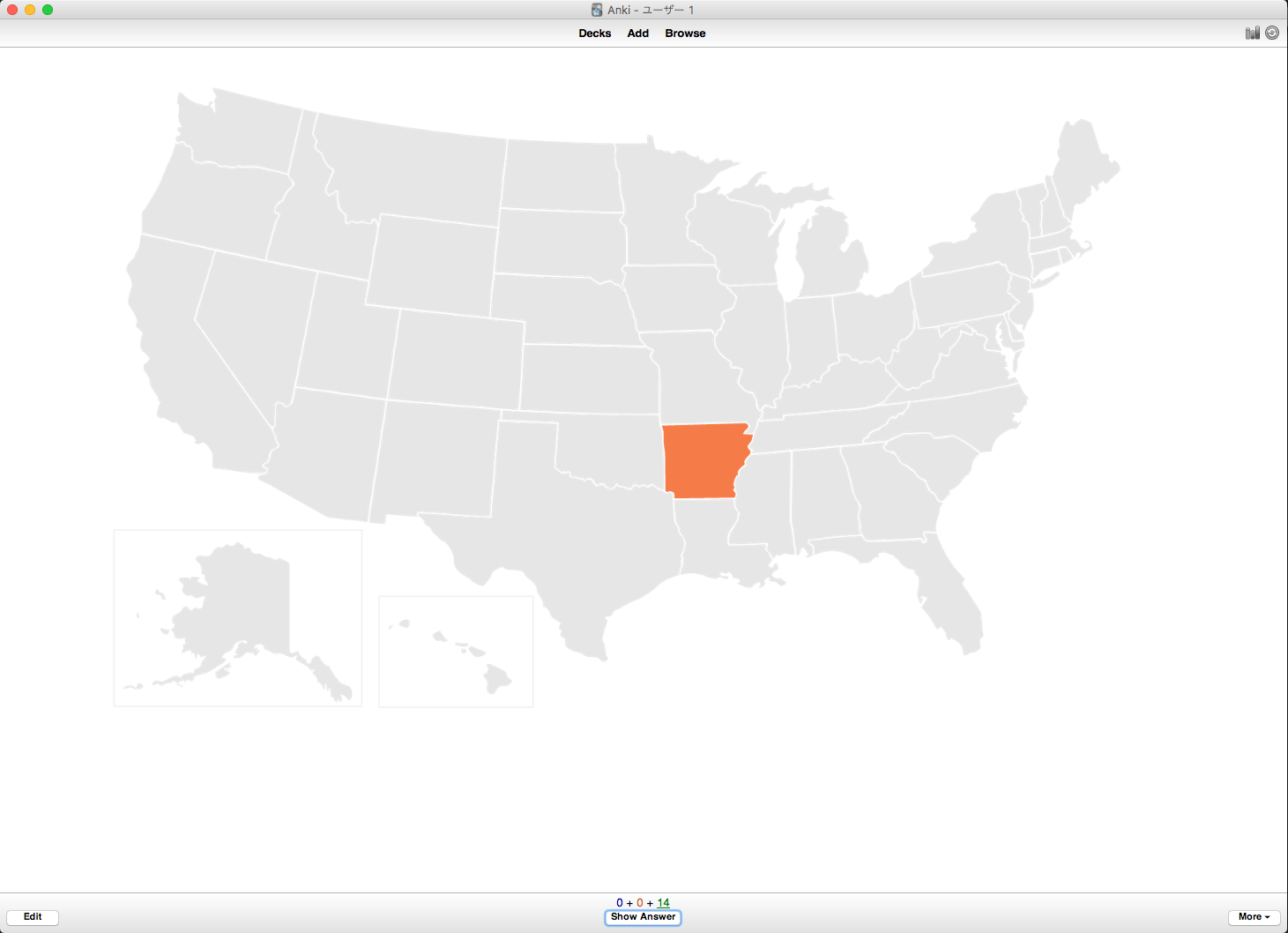

As an example, let’s step away from Japanese for a second and say I want to learn all of the states in the US. I can download a shared deck that someone has already put together with all of the states. Here’s what the front looks like:

So I look at this picture and try to remember what the name of this state is. Then I click the “show answer” button at the bottom and take a look at the back…

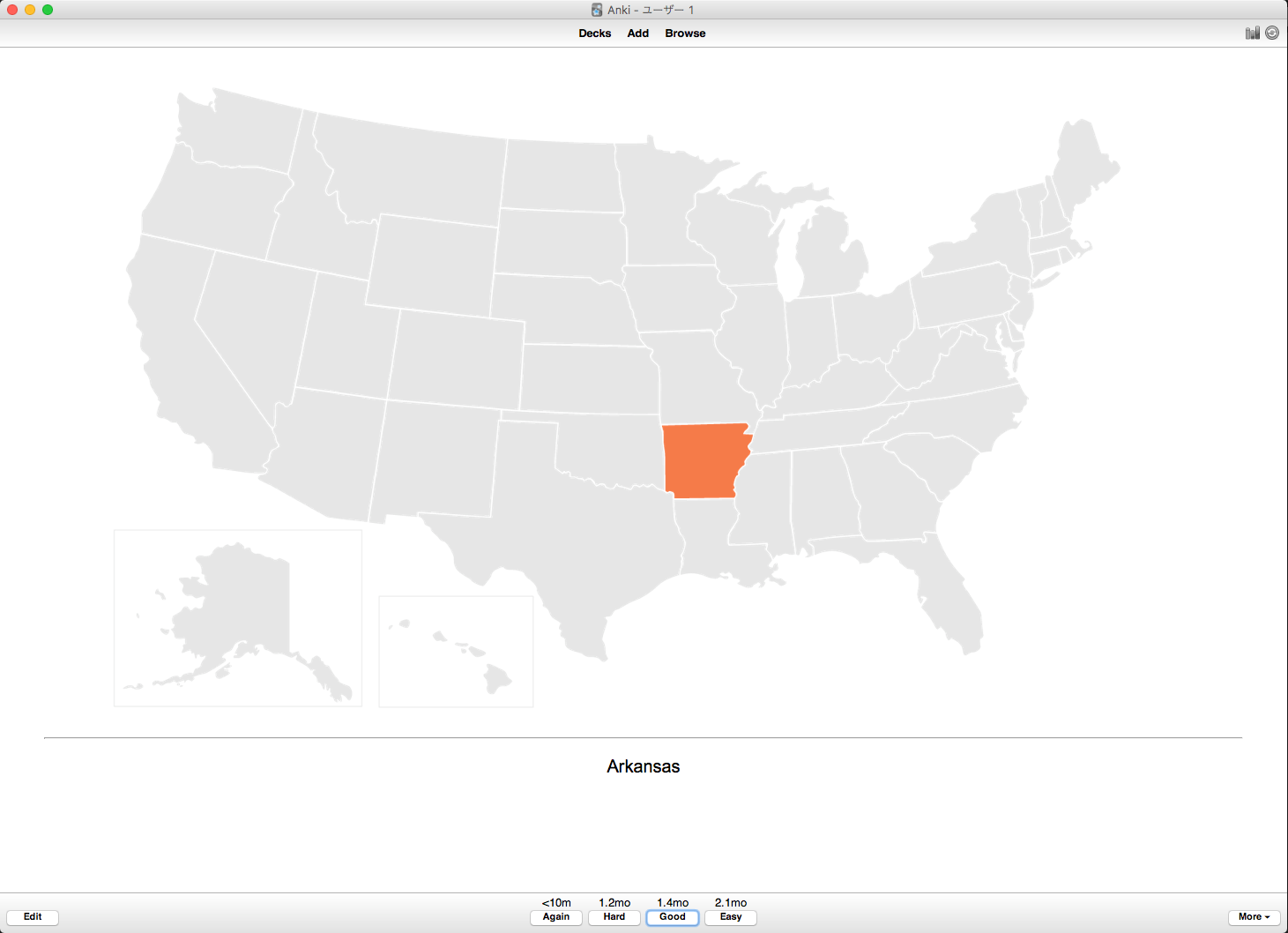

…which shows me that it’s Arkansas. At the bottom I have four button options: “Again,” “Hard,” “Good,” and “Easy.” If I forgot the name of the state, I pick “Again.” If I remembered it, but it was tough to recall, I pick “Hard.” I choose “Good” if it felt just about right, and “Easy” if I had no problem remembering the answer.

This is where the magic of Anki comes into play. Based on how easy it was to remember the answer, Anki will schedule (based on the learning curve) a review for the flash card sometime in the future. If you forgot the answer, you might review it again in a few minutes. If it was really easy, you might not see the card again for a few months or even years.

Anki helps make the process of learning thousands of small pieces of information much more streamlined and efficient. This is how we’ll learn thousands of kanji, and thousands of Japanese words.

And that’s it for part 1! In part 2 I’ll talk about learning the kana (two phonetic Japanese alphabets) and kanji.

Please let me know in the comments if you have any questions!

Posts in this series: Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3 / Part 4 / Part 5