Please do check out Part I.

Stanley Kubrick had found both his voice and strong industry support following Dr. Strangelove. It was time to move on to something new, different, grand and thoroughly unprecedented.

Already having dabbled in innovative miniature-driven visual effects with Dr. Strangelove, and now in the thick of the Space Race, it was obvious what the next spectacle was.

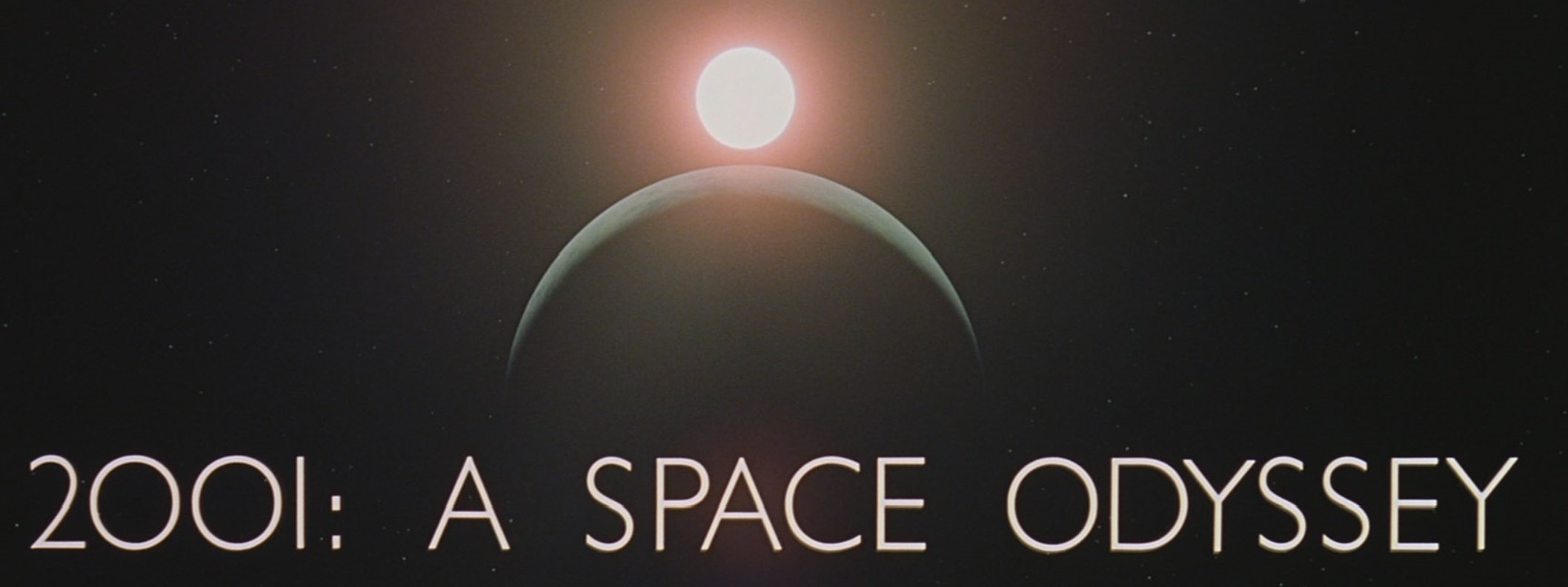

It had to be a grand science-fiction film, like no other. 2001: A Space Odyssey was co-written by Arthur C. Clarke and Kubrick himself. Much of the themes the film delves into were well in vogue at the time, building upon Asimov's work. However, Kubrick saw the immense potential of such a story told through audiovisual means.

2001 is not just a film, but a phantasmagorical experience that would transcend the ideas. For 2001, Kubrick threw out his rule book, and started afresh - what can this medium truly achieve?

"A film is - or should be - more like music than like fiction. It should be a progression of moods and feelings. The theme, what's behind the emotion, the meaning, all that comes later."

― Stanley Kubrick

From the very start, it is clear this is going to be something else. A pre-historic prologue follows a beautiful docking sequence which is a pure marriage of visuals and music.

The visual effects were groundbreaking at the time, and have aged incredibly well. Indeed, while early CGI heavy films look dated, everything from 2001 looks entirely convincing. This is the magic of miniatures and building sets. Those ships were actually built, in miniature scale, and actually lit by one point source imitating the Sun. It's not just the miniatures of course. Douglas Trumbull - the visual effects supervisor - experimented with very many pioneering techniques, from front screen projection to the slit scan photography anchoring the iconic climactic gateway sequence. Indeed, even the usually dim-witted Academy saw the innovation; the visual effects award for 2001 remains Stanley Kubrick's only Oscar.

Finally, comes the narrative. A timeless tale of machine gone rogue - a basic plot that has been imitated a gazillion times. But never in such an elegant and thought provoking manner. Nearly half a century on, it remains the most relevant science fiction film ever made.

Particularly striking too is the narrative structure - divided up into half a dozen what Kubrick would call "non submersible units". Going forward, each of his films plays with a similar narrative structure - breaking up a feature length film into many short film segments; rather than continuing down one linear plot. I feel this is the ideal structure for a feature film, while long-form TV series can better deal with the novel-like linear format. My favourite aspect of 2001 though is that the machine HAL 2000 was far more emotional than the robotic human crew! Typical Kubrick humour.

2001: A Space Odyssey is rightly an important monument in cinematic history and certainly the most celebrated of Kubrick's films. Always the innovator, Stanley sought to create something even grander for his next project.

Napoleon

There have been many highly promising but ultimately unfinished projects littered throughout history, but none more significant than Kubrick's Napoleon. 2001: A Space Odyssey was both a daring, unprecedented film and a major box office commercial success. While it opened to mixed reactions from critics, the audiences had spoken.

MGM realized they may very well have the future of cinema on hand, and gave Kubrick a massive budget to play with. With limitless resources on tap, Kubrick sought out to make a biopic about Napoleon. This would be no ordinary biopic, but a sweeping collage of the Napoleonic Wars. Just like 2001 displayed the sheer beauty of space in visceral terms, Napoleon would take on an even more daring challenge - turn war into a sensory experience that one could experience without knowing anything about military procedures.

With Jack Nicholson cast as Napeleon Bonaparte, the project was over two years into post-production when MGM pulled the plug. It wasn't to be, for numerous reasons, but mostly summarized as short term capitalist minds putting an end to a possible masterwork.

Napoleon sparked off Kubrick's penchant for research. He hired a research team and spent over two years finding every last bit of information. Indeed, the screenplay for Napoleon is filled with incredible little details. It is publicly available, by the way, and it's nothing like anything you'd ever expect of a biopic.

It's not all over though - Steven Spielberg has announced that he's adapting Kubrick's screenplay as a TV mini-series. It could take a few more years, but let's keep our fingers crossed that this one sees the light of day!

Following a messy divorce with MGM, the folks at Warner Bros - then the top Hollywood studio - took notice. They gave him a deal no other film director has ever received - carte blanche for a lifetime. Indeed, from here on, every single Kubrick film was bankrolled by Warner Bros, yet independently produced by Stanley Kubrick Productions. What this meant was, Kubrick had complete and utter control over every aspect of his films.

Burned out by attempting to put together two epics back to back (and ultimately failing) - Kubrick sought out to make something simple, low budget.

That project turned out to be A Clockwork Orange. Again, there's no film quite like it at the time. It was also Stanley's love letter to cinema itself, featuring numerous obvious references all the way from French and Japanese New Waves to Max Ophuls. Certainly his most playful film, it's one that throws the most bizarre of formal techniques at you, whether it be the erotic production design or Beethoven cut rapidly to religious symbols.

Much of the quirky language can of course be attributed to Burgess, but Kubrick took the whole novel to a completely different place. Absurd, outrageous, straddling a very thin line between the absolutely hilarious and the horrifyingly shocking - this is Kubrick's most ingenious, experimental film. Indeed, it was so far ahead of its time that it was reviled by audiences and critics alike who mistook it for a sleazy B movie. I suppose it would take them a few more decades to develop a sense of humour.

A Clockwork Orange also saw the first of Kubrick's fascination with recurring details - subtly similar events repeating themselves over the course of the film.

Alarmed by the hostile reception and death threats, Kubrick requested Warner Bros that they pull the film from British theaters - an unthinkable if not outrageous request for a director to make today. Yet, so absolute was Warner Bros' trust in Kubrick, that they duly obliged. The film was not re-released till Kubrick's death thirty years later.

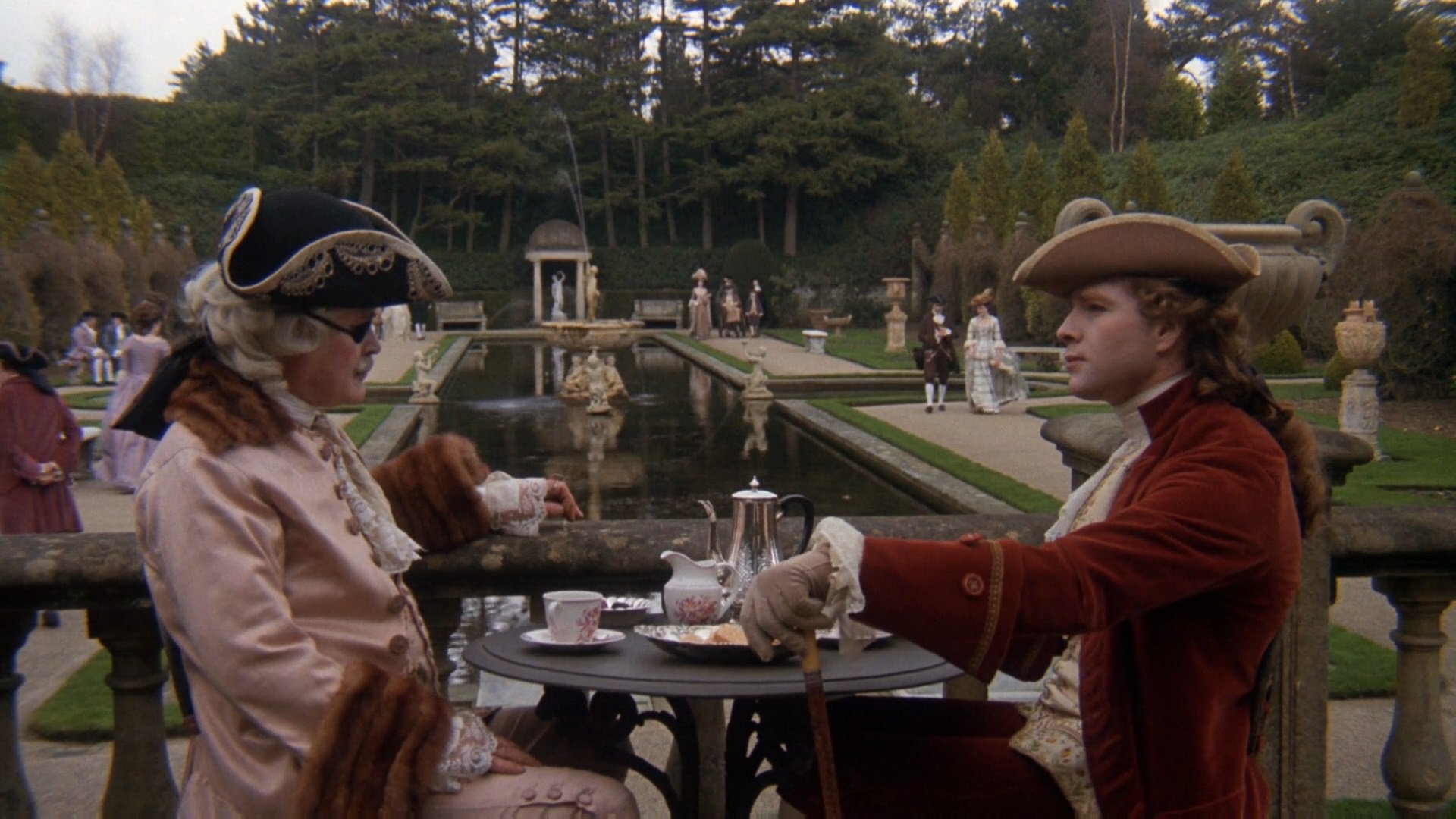

Remember those years of researching Napoleon? Luckily, they wouldn't got to waste - Kubrick used all his knowledge and then some to create ostensibly a costume drama. Yet, this is Stanley Kubrick - this is no ordinary costume drama. Barry Lyndon is perhaps a more classically picaresque character than Napoleon, which does open up more opportunities for sharp humour. Indeed, Barry Lyndon is a very funny film, though like all Kubrick films, not so apparent at first. (except Dr. Strangelove)

Barry Lyndon is my favourite of Kubrick's films - a near perfect masterwork. Whether it be the delightful use of classic music, the hilarious narrator, the extraordinary production design and photography, or the immaculate pacing - this is very near the pinnacle of cinematic arts.

I could be here for the rest of the day ranting, but instead I wish to try something different. You may have noticed I've restrained myself from sharing screenshots from these films. I wished to save that for Barry Lyndon.

Right from the very first frame, two things are clear. First, this will be quite a humourous film....

...and second, every single frame from this film is worthy of being curated for an art museum.

The deft imagery is occasionally broken up by violent handheld camerawork and rapid editing to great effect.

Extensively scouted and shot at the finest locations throughout Europe

Kubrick bought three of the ten Carl Zeiss Planar f/0.7 lenses ever made. Commissioned specially by NASA for the Apollo program, these remain to this very day the fastest lenses ever made. All night interior scenes were shot under candlelight with no artificial lighting. The trick was to use a f/0.7 lens and a very low ASA film stock for some of the most exquisite imagery ever committed to celluloid.

Another photographic innovation were the extreme zoom lenses. Then, and today, associated with amateur TV films, Kubrick made the zooms his own, giving these long, slow zooms a graceful painterly quality.

Yes, the previous shot ends up here without a cut - it's also a remarkable storytelling tool.

The finest seduction scene in fiction. A gentle ballet where actors, camera and music are precisely choreographed.

A film or a photorealistic painting?