Why do we respect other people? Because we like them or have relationships with them? Because they are capable of reciprocating? Because they belong to the same social group, or ethnic group? Or is it simply because they are humans – members of our own species?

By respect, I don’t mean admire or appreciate. I’m talking about the basic respect we show others when we try not to harm them and try to help them if we can. I try to respect everyone, even people I don’t like, because I know they can suffer and I don’t want to make anyone suffer.

I feel the same way about anyone who can suffer, no matter what their species or where they live. That includes cats and dogs, pigs and chickens, and wild animals who have no contact with humans. Just as I care about the plight of humans around the world who are suffering, I care about the plight of nonhuman animals, too. Simply because they can suffer.

What determines who can suffer?

If what we care about is not harming others and helping them when we can, then there is only one criterion that matters: sentience.

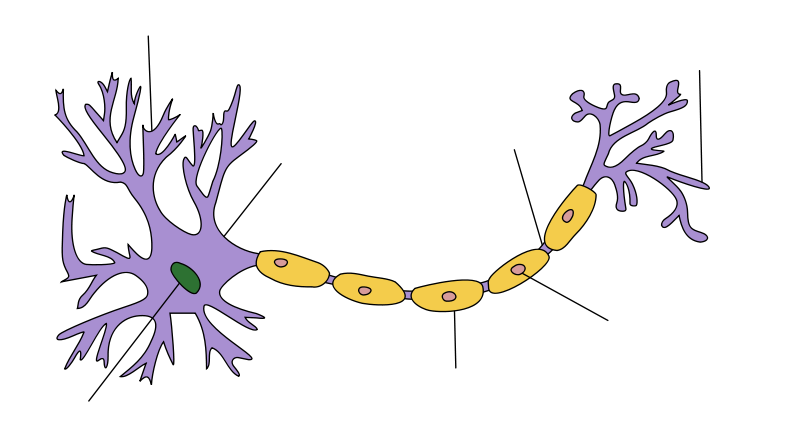

Sentience means the capacity to feel, to be able to have positive or negative experiences. Sentience depends on consciousness. We all know what consciousness is – awareness and the ability to experience life. But no one has figured out yet exactly what gives rise to consciousness. We know that it requires some kind of centralized nervous system, but we don’t know exactly how it is produced and therefore we don’t know exactly what physical structures can and cannot generate consciousness.

Just being alive or even being an animal doesn’t mean one is sentient. Without a nervous system that has at least some centralization, a living being can respond to stimuli but can’t process anything with awareness. Based on anatomy, physiology, and behavioral evidence, we know without any reasonable doubt that mammals can feel and sponges cannot, but what about the animals in between?

Until someone has solved the problem of what exactly gives rise to consciousness, we can’t say with 100% certainty. But we do know that for sentience to be present in an animal, a nervous system doesn’t have to be organized like a human’s. Octopuses and bees and even birds have quite different nervous system organization from mammals, yet the evidence is pretty clear that they are sentient.

In 2012, a group of prominent scientists including Stephen Hawking, Richard Dawkins, and Christof Koch issued the Cambridge Declaration affirming that nonhuman animals were conscious:

We declare the following: “The absence of a neocortex does not appear to preclude an organism from experiencing affective states. Convergent evidence indicates that non-human animals have the neuroanatomical, neurochemical, and neurophysiological substrates of conscious states along with the capacity to exhibit intentional behaviors. Consequently, the weight of evidence indicates that humans are not unique in possessing the neurological substrates that generate consciousness. Nonhuman animals, including all mammals and birds, and many other creatures, including octopuses, also possess these neurological substrates.”

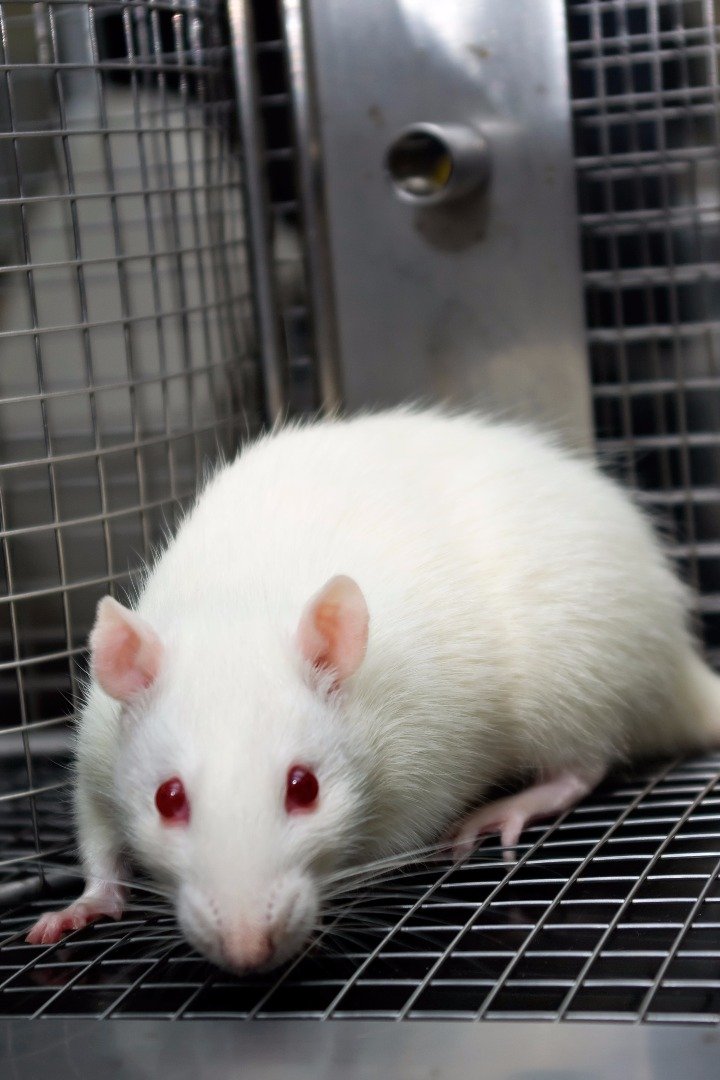

In 2009, the U.S. National Research Council Committee on Recognition and Alleviation of Pain in Laboratory Animals affirmed that pain is experienced by mammals and possibly all vertebrates.

Note that most fishes are vertebrates, and many studies have shown evidence that fishes feel pain and some species show complex social behavior.

In addition to mammals, birds, and fishes, the animals generally acknowledged as conscious include cetaceans like dolphins and whales and some invertebrates like cephalopods such as octopuses and cuttlefish.

The question of which animals are conscious mostly revolves around invertebrates. There is evidence that arachnids and insects, especially social insects like honeybees, show complex behavior that it would be hard to explain without consciousness, as well as weaker evidence for many other types of insects including flies and cockroaches.

The main reason there is not more evidence of consciousness in invertebrates is because it has been studied so little. Much more research is done on cognition in mammals and birds than on sentience in invertebrates.

Sponges have no nervous system at all so it’s pretty clear that they are not conscious. Echinoderms such a starfish, sea urchins, and sea cucumbers have no brains but a centralized nerve ring. They are generally considered to not be conscious, but little research has been done on the subject. The evidence is less clear for some molluscs like clams and oysters that live attached to rocks or on the sea floor and cannot move but have a larval stage in which they do move around. It’s possible that they are sentient and capable of feeling pain, but that it is a dim awareness.

Stimulus-response Behavior

Just being able to respond to stimuli doesn’t mean an entity is conscious. Plants have elaborate chemical defenses, hardened structures, and deep root systems that help them survive in and adapt to their environments. But they have no need of consciousness to perform any of their functions. Though there have been attempts to show that plants are sentient, they have no nervous systems or anything analogous, and no need for them. In fact, being conscious would just waste energy. It’s not like they can run away from danger!

Plants respond to light, heat, touch, and can even be carnivorous as is this Venus fly trap. But none of that requires consciousness.

Sponges, which are animals, are unusual in that they have no nerves or sensory cells. Yet they still contract when they are touched. This is an automatic response to a stimulus that requires no conscious processing.

Bivavles have simple movements like opening and closing their shells that can be explained by simple stimulus-response behavior. This doesn't rule out the possibility of them being conscious, however, since they do have centralized nervous systems and a mobile larval stage in which there is a need for active behavioral responses to their environment.

Learning

Most people studying animal behavior in the early twentieth century tended to believe that most learning, namely associative learning, was clear-cut proof of consciousness. A review of learning-related literature in present times reveals that more and more contemporary researchers find that animals, including humans, can learn some simple functions without even having any actual, conscious awareness of what we are learning. As a result, it has been argued that because humans are capable of learning without knowing what they are learning, nonhuman animal learning itself does not demonstrate consciousness.

The term “conscious” has usually not been used in scientific work relating to learning and memory. Furthermore, because learning has been demonstrated in a number of distantly-related-to-humans species such as insects, learning is now often purported as an alternative mechanism to consciousness.

Memory is the basis of learning, but memory does not always imply consciousness. Two main categories of memory are distinguished: (a) explicit memory, which relates to consciousness that we typically associate with humans, in which a subject can consciously recollect and communicate to an observer what has been learned, and (b) implicit memory, in which behavior changes due to prior events of which the subject was not conscious. In implicit memory, the subject cannot necessarily declare or state what is remembered. An example is habitual learning from trial and error which is seen in both humans and nonhuman animals.

One of the reasons animals were long assumed to have only implicit memory is because it was assumed that because they lack language, they are unable to declare these facts, and consequently unable to possess explicit memory. But this view has weakened as we learn more about how animals communicate. Animals may not communicate as humans do, but they do communicate at least some of their feelings and thoughts, through vocalizations, movement of their tails or ears, or more sophisticated movements.

Honeybees are the classic example of invertebrates displaying explicit memory, since they are capable of scouting for food sources and then returning to the hive to communicate the location and quality of the food source by doing a “waggle dance.”

“Place learning” or spatial memory has been demonstrated by other animals, including rodents, jumping spiders, and cockroaches.

Another type of explicit memory typically considered limited to humans due to it involving consciousness is episodic memory, which is remembering not only events themselves, but how they interrelated in time and space. However, studies of food-storing jays, black-capped chickadees, and western scrub jays displayed episodic memory in electing which foods to store in order to retain access to foods used to cope with anticipated states. Squirrel monkeys and rats were also found to alter their behavior in anticipation of thirst to come.

So it seems that we still have a lot to learn about learning.

Where does the evidence for sentience come from?

Physiological

Centralized nervous system

We’ve learned that consciousness exists in animals with centralized nervous systems with a complex brain, such as mammals, birds, and cetaceans. In humans, we can observe that certain activities in the brain correspond to certain thoughts or feelings, even if we don’t know how those brain activities create such awareness. We’ve seen that other animals with brains and nervous systems that are similarly centralized and complex exhibit similar signs of consciousness as humans, such as complex learning, novel behaviors, communication, and often social behavior.

For animals with simpler nervous systems that have small brains, like insects, or centralization with only ganglia and no brains, like bivalves such as clams and oysters, we have to look at other physiological, behavioral, and evolutionary evidence.

Nociception

Nociceptors are sensory receptors that respond to harmful stimuli. Nociception is a prerequisite for experiencing feeling states like pain, but it alone is not an indication of sentience because the negative sensory input has to be processed as pain in order for it to be felt, and we don’t exactly how complex the centralization of a nervous system must be in order for input from nociceptors to be experienced as pain.

Opioid Receptors

However, when nociceptors are found together with opioid receptors, that is an indication of sentience. There is no known function for opioids other than to reduce pain. Many invertebrates with simpler nervous structures have opioid receptors, including molluscs, crustaceans, insects, and worms.

Eyes

Bivalves stay in one place, exhibit only simple movements, and most have only simple light sensitive cells, none of which is evidence of consciousness. However, some bivalves like scallops have actual eyes, which may suggest that they can perceive and process visual information in a conscious way.

Behavioral

Most of us are familiar with nonhuman animals expressing feelings through body movements, the motions of their ears or tails, and it has also been observed that depressed animals tend not to move around very much and often refuse to eat.

Animals cry out in pain or fear, or express pleasure through purring or other sounds. We can tell an animal feels pain when they nurse or favor an injured body part.

People have identified “grimace scales” for rodents and rabbits to assess their pain levels. Animals trapped in cages may bite on the bars of the cage in ways we recognize as frustration.

Many animals harm themselves or attack other animals when they are stressed or frustrated.

Social behavior and responding and adapting to novel situations are also complex behaviors that seem to require consciousness.

Fear responses in other animals can look much like they do in humans.

Evolutionary

Consciousness evolved to help increase the chances of survival of animals by positively and negatively reinforcing certain behaviors and by allowing them to respond appropriately in novel situations. Maintaining an active brain requires a lot of energy, up to 20% of energy expenditure in humans. For animals that require only very simple behaviors in order to survive, consciousness may be unnecessary and wasteful.

Evolutionary logic can also help when we look at kinship, or how closely related species are to each other on the evolutionary tree. If we have strong evidence that one species is sentient, like bees, it is likely that other closely related species are as well, like ants and wasps, but it wouldn’t be such strong evidence for less closely related species like mosquitoes, flies, and butterflies.

However, since even insects whose behavior appears to be very simple do have centralized nervous systems including brains, we have to consider the possibility that all insects may be sentient. It is possible, though, that there exist insects or other animals without a sufficient degree of centralization for consciousness to emerge.

So, what's sentience got to do with it? Everything, if what we care about is not harming others and helping them when when we can.

Related posts:

@steemswede/ethology-crows-creating-and-using-tools-you-ve-got-to-be-kidding-me

@clains/the-theory-of-consciousness-a-new-era-of-science-part-one

@goose/animals-as-persons-an-introduction-to-animal-rights