Welcome to Part I of my rather long essay about Reason and Emotion - how they differ, and how they are related. It will be a pleasant stroll down a path that will touch on history, philosophy, psychology, and science. Enjoy!

Modern culture is saturated with the idea that reason and emotion are not only entirely separate faculties, but warring antagonists: “Love knows no reason,” “He was cold, and calculating, and lacked emotion,” “The jealous husband lost his head,” “Emotion clouded his judgment.” This dichotomous concept is so ingrained in our beliefs that the lover who tries to bring reason to the table is accused of not truly loving, and the thinker who reveals his passion is chided and ridiculed. But it is not only our culture that defines this basic antagonism. I believe that this separation between reason and emotion has roots in our experience as human beings. It is our existence as conscious selves, as well as the assumptions that come with such an existence, that makes this dichotomy so appealing.

Source

Even so, here I will argue that the belief in an absolute separation between emotion and reason is both artificial and debilitating. But before I get to this argument, we must first examine how and why this dichotomy first arose.

Try to consider what it must have been like to be Man at the dawn of consciousness. How can any of us ever imagine that first shattering moment of clarity when Homo sapiens discovered the boundary between himself and the world? Did it bring with it freedom or chains? Terror or illumination? Good, bad, or evil? Consciousness is Pandora's Box unopened: with it came everything.

Source

Most of us cannot remember our mini-evolution from embryo to infant, to reasoning adolescent and adult; but to be aware of Self is first to be aware of Other. One must first make a distinction between that which is his body and that which is everything else. An infant will soon recognize that her thoughts and desires will directly affect the movement of her arm or hand, but they cannot affect the bottle across the playpen. Only by moving her arm to reach for the bottle can the infant manipulate the outside world. Only through indirect means does Self affect Other. I believe there can be no more fundamental distinction. This recognition of the difference between Self and Other is a primordial dichotomy that has laid the foundation for all others.

We will probably never know how, when, or why this realization came about. Without a time machine we will never be able to pierce the dark shroud of pre-history and pre-language. All we have are speculations. But with the discovery of Other came awareness of a self; of consciousness; of existence as a willful, desiring agent. This too is an experience so basic and yet, according to our present knowledge, it is a quality found nowhere else in nature. Awareness of one's Self as an individual and uninterrupted whole – as an existence separate and almost alienated from all other existents we perceive around us – is unique to humanity.

Source

But where and how do we experience this Self? Everything else we experience is an object somewhere out there in the world. These existents are perceived and localized and known by our five senses. But one's Self is ever present yet seemingly hidden. When Man perceived his friends and brothers as objects out there in the world, yet also understood them to claim the same experience of consciousness as he, it was perfectly reasonable to separate this idea of consciousness, or self, from all other “object-stuff” found in the world. This seeming lack of spatiotemporal quality in consciousness so solidified the dichotomy between Self and Other that man further alienated consciousness even from his own body. And thus for millenia there has been a divide between spirit and matter. Recently that divide has come under question, but it is still the most basic underlying assumption of most people in the world. In order to see the historical evolution of this idea, and, more importantly, how this divide has given credence to our false belief in the total separation between reason and emotion, let us now take a brief stroll through Western philosophy.

The following is a brief and incomplete survey of Western philosophy. It will be a survey based on my own limited readings of this select group of philosophers, and it will be hampered by my own admittedly limited understanding. The reader should also keep in mind that the following is a list of men whose genius and ideas have withstood the ever-destructive hands of time, and that this is no small feat. If in my writing it seems that I brush their ideas and definitions aside with too much ease, and too little grace, know that, like Isaac Newton before me, I understand that I am but a pygmy standing on the shoulders of giants. It is only my historical placement – this age of scientific method, psychological principles, and neurological discoveries, which these men helped to create – that might allow me to see a bit further than they, if not to Truth, then at least to truth.

Source

Early man had no definitive conception of the soul. The Hebrews of the Pentateuch spoke only of a dark underworld called Sheol where the egoless ghosts of the dead wandered for eternity. And when Odysseus visits Hades, Homer's Achilles so hates his lifeless state that he would prefer “to work the soil as a serf on hire to some landless impoverished peasant” than be king of all the lifeless brethren that surround him (Homer 173). Before Socrates, in fact, Greek philosophy and religion hardly ever mention the idea at all. Socrates is one of the first recorded men of the West who stated that the soul is something within us, a thing special and valuable that encapsulates our personality and moral nature (Collaiaco 137). But it was not until Socrates' student Plato reinterpreted his teacher's lessons that the soul became immaterial, perfect, and immortal. Plato concretized this idea with myth, and cemented the myth with dialectic.

Plato was a genius, and an aristocrat, who lived much of his life in a tumultuous time of war, famine, and instability. Born in 427 BCE, he lived his first twenty-three years in a state of war. Plato witnessed the fall of his city, Athens, at the end of the Peloponnesian War, and he forgave neither the relativistic sophists, nor the heterogeneous demos, who he blamed for the city's greed, hubris, and instability. At twenty-seven he mourned over the death of his teacher and mentor Socrates, who had been executed by the weakened but newly reincarnated democracy. Plato, like Heraclitus who preceded him, now believed existence to be a never-ending flux of change, and the unpredictable period he was born into could only support this belief. But he could not accept this as the final truth. Plato knew that man cannot live in a world where there is no anchor, no foundation, no ability to judge right from wrong and truth from falsehood. And so he postulated a world beyond the material. Plato created a world that is both changeless and perfect, a world of Forms that shines occasional light into the shadowy cave of existence.

Plato's Cave Metaphor

Plato's world of Forms is a land of numbers and angles, of concepts and ideas; it is the world of the soul or mind, but it is not the mind of any finite, fallible human. It is a vast universal memory bank out of which all intuition springs and where all thoughts are first conceived. Here in this world of Forms one can find stored all the concepts that underlie our imperfect perceptions. It is existence made changeless and immortal, and it is heaven for all those who seek refuge from the instability of living.

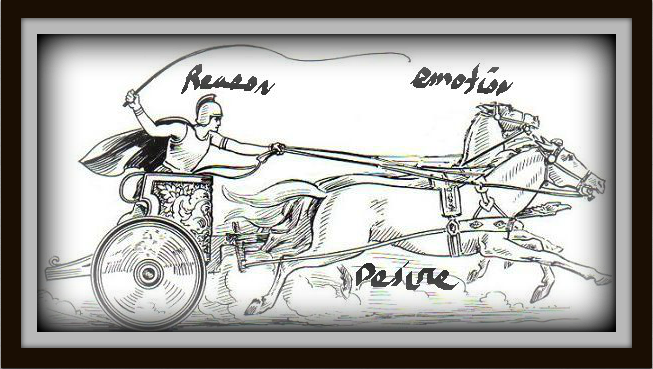

To accept this divided world, one must embrace a bifurcated Self. If the objects in the world are only incomplete shadows of their perfect, super-natural Forms, why not Man himself? Here we see the birth of soul or Self existing apart from, and even in opposition to, the body. But Plato does not only distinguish between the soul and the body. In the Republic he further splits the soul into three parts: appetite, spirit (or passion), and reason. Appetite is desire, and it is the slave of the body. Appetite is thirst and hunger and lust. Appetite makes up the majority of soul and must be tamed if an individual is to be happy (Plato 156). The second aspect of soul, the spirit, includes such things as anger and disgust and fear (Plato 157). While irrational, the spirit seems to be an intermediate bridge between appetite and and that third slice of soul, reason, in that it usually acts to keep appetite in check.

Source

Reason, finally, is the intellect set free from the body, and it must remain in charge of the soul (Plato 155). It is the only part that can get a glimpse of the world of Forms and, presumably, it is the only part of the soul that lives on after the body perishes. For Plato, reason is the essence of Self, and in the Phaedrus he describes it as the charioteer driving and guiding the two unruly horses, appetite and spirit (Plato 253c-254c). Here we see one of the first and clearest examples of, not only a dichotomy between soul and body, but a tripartite distinction between desire, emotion, and reason.

Okay - that's it for Part I. This will be broken down into several parts, and you can find Part II HERE.

If you found this post interesting and/or useful, I certainly appreciate all upvotes and follows. And I'd love to continue the conversation in the comments below. Thanks for reading

References

- Colaiaco, James A. Socrates Against Athens. New York: Routledge, 2001.

- Homer. The Odyssey. Trans. E.V. Rieu. London: Penguin Books.

- Plato. Phaedrus, The. Trans. Desmond Lee. London: Penguin Books, 1974.

- Plato. Republic, The. Trans. Desmond Lee. London: Penguin Books, 1974.