We often take movement and its importance in our overall life for granted. We spend our whole lives running and playing, traveling and exploring. This would be impossible if we couldn't move, but how much do we really understand about movement? How do we learn to swim and run and how does understanding movement help some people become Olympians or dancers and other professional athletes? Life Explorers - Movement is an journey ito the magic of movement and how we learn to do it to improve over time.

The wonder that we experience in life would be largely impossible if not for movement. So how does it work?

Planes

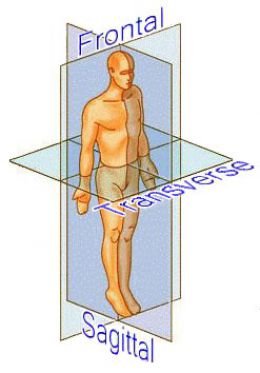

First it's important to understand the ways we can move. Since we live in 3D space, we can move up and down, side to side, as well as forward and backwards. These directions are known as Planes of Motion.

Planes of Motions describes the limits and directions that our limbs can move. These, in turn, dictate which muscle groups activate to allow for the desired movement. Our joints in combination with muscle allow for movement in these specific ranges. Above, the anatomical position shown is considered to be the starting point for many movements, and is regarded as the resting anatomical position.

Frontal Plane

This plane separates the body into front and back, with movement happening along the plane. So when we're doing a wide-grip pull up or lifting light weights up from our sides, we're working in the frontal plane. Whenever we do a jumping jack, our arms and legs are moving in this plane. The joints involved include the knee, hip, and shoulder. Movement in this plane is described as adduction and abduction.

- Adduction is when movement happening in the frontal plane travels towards the midline of the body. An easy way to remember this is by imagining that when you do the movement you are "adding," or moving towards the midline.

- Abduction is when this movement is reversed, with limbs moving away from the midline in the frontal plane. To remember this, think of your arms being raised away from your body, or "abducted". When you raise a weight straight out to the side, you're abducting because your arm moved from resting anatomical position away from midline. When you raise your arm to wave goodbye, the arm is abducting from the body.

Sagittal Plane

Imagine a straight line down the middle of your body and you can see that in the sagittal plane, the body is divided between left and right, with movement occurring forwards and backwards. If you were to lift a weight straight out in front of yourself, you'd be working in the sagittal plane, and performing one of the two movements that exist for this plane, Flexion and Extension.

Flexion describes movement going forward in the sagittal plane, when you exert greater force than the resistance (weight). When we push from a push up, our shoulder joint engages in flexion while our elbow joint performs extension.

Extension is essentially the opposite of flexion. When you raise a dumbbell directly in front of you, you must perform flexion to get there. If you are pulling down cables in front of you, however, you are performing an extension to get there.

Transverse (Horizontal) Plane

Think about when you go to hug a family member or a spouse. When you bring your arms in around them, that is a movement that happens in this plane. The human body is divided into upper and lower halves, and an easy way to identify this movement is in a wide-grip push up. Unlike the close-grip, a wide-grip push up forces your elbows to flare out to the sides and re-positions your shoulder joint into the horizontal plane. Movement in the transverse plane includes Horizontal abduction and Horizontal adduction.

- To easily identify Horizontal Adduction, think about that hug from earlier. When you closed your arms around your loved one, you were bringing them closer to your midline, or "adding". At the shoulder joint, the same movement occurs when you do a wide-grip push up or pull up.

- For Horizontal Abduction, imagine you have a large bag of chips that you grip with two hands and rip open. You pulled your arms out to rip open the bag, and the travel away from the midline is what identifies this.

Those are the ways we can move, but how do we even learn to do all that?

Control, Learning and Development

Our motor control is made up of our posture and how we move, in relation to the systems like the central nervous system. Over time and as we have more experiences in the physical world, this control is refined. Developing children start unable to even raise their head but within a short amount of time are able to stand and even walk. Our impulse to stand up out of a seat, for example, requires an integrated response from a number of systems working together to perform the action. But in your mind, you just decide to stand up and do it.

This happens without conscious thought because with motor control, muscle synergies develop. These synergies make the necessary muscles act as a functional unit, and help us move around in the world without too much conscious thought.

The process of gathering and using this data is called motor learning, and it is responsible for olympic athletes, martial arts experts, dancers, and anyone else involved in a movement based discipline. With more practice, we reinforce the processes between mind and body. For example, the first time you do a push up, the chances are that you will not do it perfectly. However, with time and practice, motor learning helps us achieve much better form and execution. If you take up a fitness class and feel sore after the first day, you're experiencing the internal feedback associated with motor learning. This soreness will fade over time as the relevant muscle groups become accustomed to moving in the respective planes.

Over a large period of time this process is known as motor development. We can measure our motor development when we participate in fitness routines and use metrics that we record to chart our progress. When we develop our motor skills to a high enough level we're able to perform all kinds of complex movement.

Thank you for reading this edition of Life Explorers: Movement. Now that we have a basic understanding of movement, next time we can examine the biochemical processes that occur that enable our muscles to respond to our demands.

Author's Note:

The Life Explorer Series is a community magazine that brings together writers to post about a variety of topics. All topics and authors using the lifeexplorer tag or title are part of this group and have permission to post under the heading Life Explorer. If you would like to write with the Life Explorer series about a topic, reach out and get in chat contact with @timsaid to learn more.

Make sure to catch all these Life Explorer authors:

@prufarchy

@yogi.artist

@disofdis

And if you've missed the previous edition, check out some other Life Explorer posts:

Life Explorers - The Human Senses Part I: Sight by @timsaid

Life Explorers - The Human Senses Part II: Hearing by @timsaid