Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7

Part 8 | Part 9 | Part 10 | Part 11 | Part 12 | Part 13 | Part 14

Part 15 | Part 16 | Part 17 | Part 18 | Part 19

Is capitalism to blame for overconsumption? Certainly our shopping habits have been enjoyed by big corporations and maybe even encouraged in their advertising.

But do corporations really have that much power over us? Corporations can't pass laws that force us to spend. Corporations can't adjust the money supply to make it less smart to save. Only the government can do those things, and only the government has done them over the last hundred years.

And there's another thing corporations can't do that a government can: create bubbles. A bubble is an unsustainable and unwarranted rise in an item's price. The only changes in price that are truly warranted are when there's a change in how much a product is supplied and/or demanded. Supply and demand are market forces. But when prices go up for other reasons, this isn't capitalism at work. This is a government at work.

So let's look at a famous economic bubble to see how these bubbles are formed. In 1636, Holland experienced a tulip bubble. In November, the normally stable price of tulip bulbs started to rise. The price got so high that someone offered 12 acres of land to purchase one bulb of the Semper Augustus variety! But in February of 1637, just three months later, tulip prices collapsed and many Dutch tulip speculators went bankrupt.

We might think that people had been buying more and more tulip bulbs in 1636, and that as more and more people tried to buy them, the prices went through the roof. But that's not what happened.

What did happen was that the Dutch government had increased the supply of money in Holland. (They did this through a “free coinage” law.) And whenever the money supply is inflated like a balloon, investment bubbles usually follow. That's because more money circulating in the economy lowers interest rates. This makes it cheaper to borrow money. And when money is cheap to borrow, it stimulates something called malinvestment (a bad investment).

Buying up tulips bulbs in late 1636 was a malinvestment. But it looked like a good investment, and that's the trouble. When prices go up, whether because of market forces or government manipulation, we tend to react to those price signals the same way. We assume that high prices mean that economic conditions are favorable - that the market for tulips, in this case, is healthy. It seems smart to get in now because the demand for tulip bulbs seems to be going up.

But demand for tulips wasn't going up – just the price.

Bubble prices don't reflect a true or sustainable demand. Bubble prices reflect the lowered price of money. That's what makes it a malinvestment. Rather than investing in something sustainable, you're investing in something that's been manipulated to look sustainable.

Nevertheless, tulip bulb producers in Holland saw the higher prices and started scraping together all the bulbs they could find. They imported them. They dug them out of warehouses. They dug them out of their own gardens! And as the supply of tulip bulbs reached epic heights to capture these high prices, the effect of money inflation started to lose steam. The laws of supply and demand kicked back in. The oversupply of tulips, combined with a newly lowered supply of circulating money, caused tulip prices to fall sharply.

Bubbles tend to enrich large business corporations at the expense of consumers, and because corporations are getting richer and bigger, we assume this is the fault of capitalism. But it's actually the government creating unsustainable economic growth by inflating the money supply. And it's only when bubbles pop that we blame capitalism and free markets. (And ask the government to pass more laws.)

The problem really boils down to the fact that markets aren't free. They never have been. Governments have been manipulating markets with laws for as long as governments have existed. And one of the ways they manipulate markets to increase prices, create bubbles, and drive overconsumption is by playing on our fears about the environment. We'll see an example of that next time.

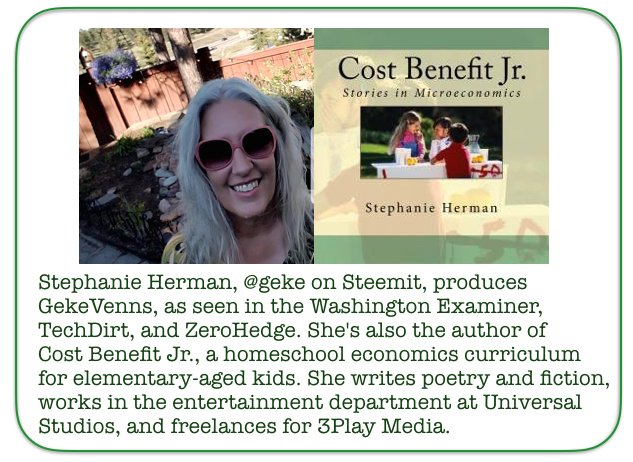

This article is one of a series I'm writing for the 30 Day Writing Challenge hosted by @dragosroua. If you want to join, write on a topic that interests you or that you'd like to learn more about and use the tag #challenge30days. As Dragos says, "The key word sequence here is: "write every day."

Think you'd like to wash up on our shore?

The treasure map will bring you right to our door!