- How Old Is Newgrange? (Part 2)

Thomas Molyneux Begs to Differ

In Part 4 of this series we saw that the Irish antiquary and Fellow of the Royal Society Thomas Molyneux first learned of the discovery of Newgrange from his Welsh colleague Edward Lhwyd, who wrote to him on the subject in January 1700. A few years later Molyneux visited the site in person and examined the monument for himself. In 1726 he published the results of his observations as an appendix to a revised edition of Gerard Boate’s The Natural History of Ireland. Taking his cue from the Danish antiquary Olaus Wormius, he attributed Newgrange and similar megalithic structures in Ireland to Scandinavian colonists—ie Vikings, or Danes:

... tho’ the way of burning the dead, and putting the remnant of the bones and ashes into urns, was frequent here among the Danes; yet we find likewise the greatest chiefs and princes of that nation, even in the time of paganism, affected sometimes another kind of burial whilst they were here in Ireland; committing to the grave their dead bodies perfectly entire, after the manner of the christians, but still retaining the common custom of their country, of being interred in caves, under high artificial mounts.

Of this way of burial Wormius takes notice likewise, as practised by the Danes at home but thinks it was of a later date than that of burning: (i) The second age (says he) was that in which the entire corps[e], not burnt, was placed ,with all its ornaments in a round hollow, whose sides were made of large stones, and covered with the same at top, over which they heapt so much earth and sand, till it equalled the height of a little mountain, and which at last was adorned on the outside with green sods and other stones set round it.

A sepulchre of this kind we have at New-Grange, which for the large circumference, and extraordinary height of the mount over it, the contrivance of the Cave within, the outward ornaments that surround the mount, and the two smaller adjoining mounts, is so very singular and remarkable, that it well deserves a more particular description. ’Tis situated in the county of Meath and barony of Slaine, within four miles of the town of Drogheda; from its largeness and make, from the time and labour it must needs have cost to erect so great a pile, we may easily gather ’twas raised in honour of some mighty prince, or person of the greatest power and dignity in his time. (Molyneux 202)

Molyneux was possibly the first antiquary to claim that human remains were found in the tomb:

When first the cave was opened, the bones of two dead bodies entire, not burnt, were found upon the floor, in likelyhood the reliques of a husband and his wife, whose conjugal affection had joyn’d them in their grave, as in their bed. (Molyneux 204)

Edward Lhwyd had previously recorded the discovery of animal bones in the mound, but he had not mentioned human remains. He did, however, mention in passing some other things, which I omit, because the Labourers differed in their Account of them. Perhaps these other things included the two skeletons referred to by Molyneux.

Molyneux also described two Roman golden coins that were found in Newgrange, one of Valentinian I and the other of the emperor Theodosius. Lhwyd had mentioned the first of these and had considered it proof that Newgrange predated the Danes. But Molyneux was not so easily convinced:

This Roman money, must certainly have been brought into Ireland by the trading Danes, as being the current coin at that time in commerce throughout Europe, and received in exchange for such commodities as these Easterlings carried abroad. (Molyneux 206-207)

Is this true? Was Roman money still being exchanged in Europe four centuries after the collapse of the Western Empire? My own research has failed to substantiate this claim. Nevertheless, there is evidence that the Vikings used obsolete Roman coins as ornaments and precious objects, and such coins have been found in hoards in Scandinavia:

The earliest coins found in Norway are Roman coins, struck from Romans Republican times to the early fifth century. Their date of deposition is particularly hard to establish, but many of these coins seem to have been in circulation for a long time: for example, a Roman denarius struck AD 119-22 was found in a burial mound in Aust-Agder dated to c.400, and the Hoen hoard, from the later ninth century, included a fourth-century coin. (Naismith et al 357)

So it is possible that the coins of Valentinian and Theodosius were deposited in Newgrange by Vikings sometime in the Middle Ages. Molyneux’s hypothesis that the monument was constructed from scratch by the Danes is certainly not refuted by the presence of Roman coins on the site. Against this hypothesis, however, it can be argued that the two coins were found to be in good condition, suggesting that they were deposited shortly after they were struck. This point was raised by the Irish clergyman and travel writer Thomas Campbell in a letter to John Watkinson, which was published in London in 1777:

I was surprised to find the ingenious Mr. Molineux ascribing them to the Danes, especially as he mentions two coins of the emperors Theodosius and Valentinian, being found in that famous Tumulus, at New Grange, near Drogheda. This, though not a decisive evidence, is certainly a presumptive one, that these sepulchres were anterior to the Danes in Ireland; and the rather, as those coins are described to be sharp and unworn (Campbell, Letter 18).

Molyneux’s Danish hypothesis became probably the most popular interpretation of Ireland’s megalithic structures, and remained so for more than a century. Danes-Mounts entered the antiquary’s vocabulary, but the expression was not coined by Molyneux, and he did not claim priority in attributing these burial mounds to the Danes:

These sort of pyramids or artificial hills, are found not only in this country, but in some parts of England, tho’ not near so common, nor as I think so large as ours. The English call them barrows or burrows, from the old Saxon word, beorg or burg, a hill, from whence we derive our modern word to bury, and burial, as the Latins us’d the word tumulus to express both a hill and a grave. As to the reason of this ambiguous use of the same word in these different languages, we may take occasion to say more hereafter in discoursing upon the original of sepulchral monuments. The old Irish or Scots call them carns, which in their language signifies a heap, but more especially of stones piled together, of which some are composed, as others are of earth: with the English of Ireland they pass under the name of Danes-mounts, from a current and constant tradition, receiv’d from the Irish, that they were first raised by the Danes when they were in possession of this country. (Molyneux 190-191)

Among the many antiquaries who were sufficiently persuaded by Molyneux to attribute at least some of Ireland’s ancient burial mounds to the Danes was the historian Walter Harris. He devoted many years of his life to translating the works of his 17th-century predecessor James Ware from Latin into English. Not content to simply translate Ware’s writings on Ireland, he also revised and improved them with many material additions. These addition included several intirely new chapters by Harris himself. In his translation of Ware’s De Hibernia et Antiquitatibus eius Disquisitones (The Antiquities of Ireland), Chapter XVII—Of some Monuments of Antiquity in Ireland; by whom erected and for what Uses—was one such addition. In Section II of this chapter, Harris followed Molyneux in attributing Ireland’s megalithic burial mounds to the Danes:

The Danish writers have been more than ordinarily industrious in preserving and publishing the ancient Monuments of their Country; and as these Northern People domineered in Ireland for upwards of 400 years, it is not to be questioned, but that during the long Continuance of their Power they raised in this Country many such Mounts, and especially in the Northern Parts, which first felt their Rage; but to exclude the Irish or other Nations from the same Kind of Structures, would, from what has been said, appear unreasonable. (Harris 137)

In a later chapter—Chapter XVIII: Of the Funerals, Places of Sepulture, and Subterraneous Vaults of the Antient Irish and Ostmen, in Ireland—we read the following passage, which Harris added to Ware’s original:

Molyneux gives us a Description of the first Sort of these Sepultures [large spacious Vaults], discovered in a Mount at New Grange, in the County of Meath, which being very exact and particular, I shall make free with. Having described the Mount, he proceeds thus... (Harris 146)

Harris then went on to quote in extenso Molyneux’s remarks on Newgrange, adding no comments of his own. Significantly, he did not question Molyneux’s attribution of the mound to the Danes, though just a few lines earlier he had cautioned against drawing hasty conclusions:

But we must not with that Writer [Molyneux] too hastily conclude, that these were the Funeral Places of the Danes alone; since the same Practices prevailed among the Irish, and therefore they may be indiscriminately applied to either People. (Harris 146)

Another eighteenth-century disciple of Molyneux was Charles Smith, whose occupations included topography, medicine and the study of antiquities. His principal work, The Ancient and Present State of the County and City of Waterford, appeared in 1746:

In this county, as in most of the other counties in Ireland, we meet with three kinds of ancient monuments, which are justly attributed to the Ostmen or Danes ... The third kind, called, in the language of the country Dùn, are those called barrows in England, and are no other than sepulchral mounds ... Concerning the inside of these artificial hills, I refer the reader to Dr. Mollyneux’s account, published in the appendix to Boate’s natural history of Ireland. Not only the ancient Greeks and Romans had their Tumuli, but also the Danes and other northern nations, as Olaus Wormius informs us. (Smith 351 ... 353 ... 354)

Henry Rowlands

Although Molyneux’s account of Ireland’s megalithic structures was written around 1710, it did not appear in print until 1726. Three years earlier, another antiquary, Henry Rowlands, had published an account of similar monuments on the island of Anglesey. Mona Antiqua Restaurata did not concern itself with Ireland, but it was published in Dublin, sold well, and had a pronounced influence on the interpretation of Irish antiquities by our native antiquaries. Like Molyneux, Rowlands was a correspondent of Edward Lhwyd: the latter had communicated his initial impressions of Newgrange to him in March 1700. Unlike Molyneux, however, Rowlands did not attribute the megaliths to the Danes.

In Mona Antiqua Restaurata, Rowlands hypothesized that the megaliths of Anglesey were intimately associated with the religious practices of Druidism, which he understood to be the religion of the first inhabitants of these islands:

... from the effects and visible monuments of this first religion, we are left to guess at the cause and quality of it. Of this sort of evidence we have one great altar of stone, of considerable bigness, upon the bank of the river Menai, now in the parish of Llan Edwen, which may seem to have been, as the biggest, so the first and chiefest one of the whole island; whereon the first-fruits of the place might be offered to God by those very first men who came into it. Though afterwards other such altars were erected for the religious worship and the performances of oblations and sacrifices in the several colonies of it, of which not a few remain standing here and there to this day.

These altars of stone (where stone served to raise them up) were huge broad flattish stones mounted up and laid upon other erect ones, and leaning, with a little declivity in some places, on those pitched supporters; which posture, for some now-unaccountable reasons, they seem to have affected. These altars were and are to this day vulgarly called by the name of Crom-lech... (Rowlands 47)

If Anglesey’s megaliths were admitted to be of Druidic origin, it was only natural to suppose that so too must the megaliths of Ireland. Noting the congruity of language between the two islands of Ireland and Britain, Rowlands added:

I mention this here to shew the original agreement between the ancient Irish and the Britons in custom and language, greatly betokening their being at first one and the same people, that is, the one a colony of the other. (Rowlands 30)

One example of the lasting influence Rowlands had on the interpretation of Ireland’s antiquities is Jacob Des Moulins’ Antiqua Restaurata of 1794:

On the tops of the mountains of Scotland, Wales, Ireland, the Scotch islands and the Isle of Man, are great heaps of stones, another relique of the Druids. (Des Moulins 37)

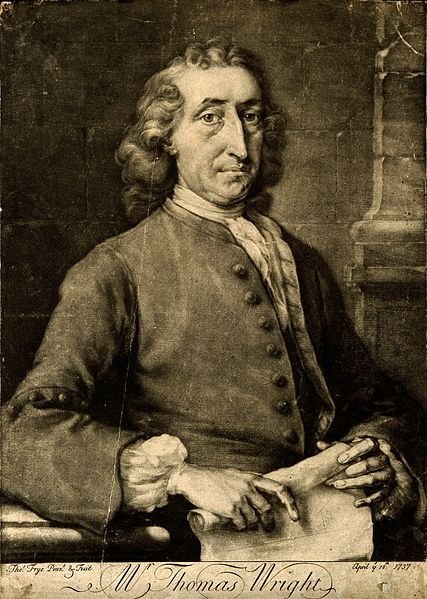

Thomas Wright

Thomas Wright, the accomplished astronomer, architect, artist and landscape designer, visited Ireland in 1746-47. His extensive collection of architectural drawings and engravings—published in Dublin in 1748 as Louthiana: Or, An Introduction to the Antiquities of Ireland—set a new standard in draughtsmanship. Louthiana also included some fine drawings of the Boyne Valley monuments, including Newgrange, which Wright visited on more than one occasion. Regarding his opinion of Newgrange, we have the following comment from a later writer:

Mr. Wright, in his additions to the Louthiana, a MS. in the possession of the respectable Mr. Allan of Darlington, says, New Grange is the oldest monument he examined in Ireland. On first entering the Dome, not far from the centre, a pillar was found, and two skeletons on each side, not far from the pillar. In the recesses were three hollow stone-basons, two and three feet diameter. But when he visited New Grange again, in 1746, these basons had been removed, and placed upon one another. One of the cells had an engraved volute, which he supposes was dedicated to Woden, or Jupiter Ammon; another had lightning cut on its lintel, as sacred to Thor. (Ledwich 44-45)

The manuscript Ledwich refers to has, to the best of my knowledge, not yet been published. I have not been able to lay my hands on a copy of Louthiana, or hunt down an online source, but an online critique of the work dismisses Wright’s theories in a few words:

The above-mentioned works also share another characteristic: an archaic and frequently convoluted style of prose. This was the inevitable result of the general ignorance in the 18th century of the dynamics of past societies let alone the time-lines of prehistory. The only written sources from which they could glean parallels for what they were recording were the occasional references to monuments in the Bible and the writings of Greek and Roman scholars. In the case of Louthiana, the result is rambling text full of overblown theories that attribute all monuments to the Danes. (Ask About Ireland)

Book III of _Louthiana_ was entitled; _The Most Remarkable Remains of the Works of the Danes and Druids_, so it would appear that Wright did not _attribute all monuments to the Danes_. Nevertheless, the reference to [Woden](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Odin) in relation to Newgrange implies that he did attribute that particular monument to the Danes.

Thomas Pownall

Thomas Pownall, the former Governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, visited Newgrange in 1769. He believed that some markings on the stones of Newgrange were of Phoenician origin. This led him to the following imaginative hypothesis:

I am inclined to suppose there may have been, ages before this Barrow was erected, some marine or naval monument erected at the mouth of the Boyne, by some of these Eastern people, to whom the ports of Ireland were well known: that this monument, through the course of events and time, fell into ruin, and that these ruins were collected amongst the rest of the shore-stones with which this Barrow was constructed, and so was intermixed, and became part of it: that the peculiar and secreted situation of this stone became a peculiar means of its being a singular instance of the preservation of the only eastern or Phœnician inscription found in these countries. Those whom this

conjecture cannot persuade, may, however, profit by the hint, and possibly amuse themselves in suggesting some more rational account of this matter. I mean to assist the conjectures of others, not to impose my own. (Pownall 259–260)

He did add, however:

Before I close this description, I would just observe, that there are on some of the stones which form the sides and backs of the Kistvaens [ie the cells or recesses adjoining the central chamber in Newgrange], lines cut in a spiral form. In the front edge of one of the stones which form the top of the Kistvaens there appear some lines forming a kind of trellis-work, in small lozenges, such as are not unfrequently seen on Danish monuments and crosses. (Pownall 260)

These northern people, during a long series of years, made repeated inroads into, and kept possession of, many parts of the British Isles, and were in fixed and settled possession of Ireland for near four hundred years. Many of their princes and warriors died in these Isles; and it is certain that many of the Barrows, found in most parts of Britain and Ireland, are their sepulchral monuments ... It will not appear therefore a far-fetched conjecture, if I suppose our Barrow to be of Danish construction. (Pownall 267)

Pownall, therefore, believed that Newgrange was of Danish construction, but that some of the stones used in its construction were taken from Phoenician ruins near the mouth of the Boyne of a much more ancient date (Pownall 255). Phoenician colonists, he believed, established the Druidic cult in these islands and introduced to the primitive Celts many of the blessings of civilization: the arts of animal husbandry and agriculture, the plough, the war-chariot, religion, faith and religious rites (Pownall 242-244). This hypothesis—that Druidism was not native to the Celts but was introduced by missionaries from the east—deserves to be looked into and not simply dismissed as fanciful.

Ledwich

In 1790 the Irish antiquary Edward Ledwich published The Antiquities of Ireland, which contains a lengthy description of Newgrange and a summary of the most recent scholarship relating to the monument. He comes down firmly on the side of those who attributed the structure to the Danes. The discovery of uncremated bodies was of great significance to him in this regard:

I am clearly of opinion the construction of mounts, or, to speak with Wormius, the age of hillocks was much later, for the Brende-tiid, or age of cremation certainly had not ceased in the North or Germany in 789, for a capitular of Charlemagne, of that year, punishes with death such Saxons as burnt their dead after the manner of pagans. Christianity had been long preached among the subjects of this prince, and yet they were still but half Christians. It is evident from the contents of our cave that cremation had ceased among the Ostmen in Ireland, they also shew the dawnings of christianity among them; every other circumstance evinces pagan ideas. This might reasonably be supposed to happen at the period of their conversion: then we might expect to find in the same structure some indications of their new, and many of their old religion: for an instantaneous dereliction of their ancient creed never occurred among a rude people. The Irish Ostmen embraced the faith about 853, and in this century I think we may date the construction of the mount at New Grange: it was made and adorned with every sepulchral honour to the memory of some illustrious northern chief. (Ledwich 46)

Charles Vallancey

Eighteenth-century speculation about Newgrange and its megalithic relatives culminated in the writings of Charles Vallancey, whose Collectanea de Rebus Hibernicis appeared in six volumes between 1770 and 1804. Vallancey was a military surveyor, but the history, philology, and antiquities of Ireland became his passion.

Posterity has not been kind to Vallancey or his speculations. Ridiculing the man and his writings has been a popular pastime of Academia for more than two centuries now. I am inclined to believe that many who play this game today are as ignorant of Vallancey’s works as they suppose him to have been of Irish history. In The Dictionary of National Biography, Norman Moore pronounced the following obituary as he buried Vallancey’s hypotheses:

The Collectanea de Rebus Hibernicis, 1770–1804, in six volumes, Vindication of the History of Ireland, 1786, Ancient History of Ireland proved from the Sanskrit Books, have the same defects. Their facts are never trustworthy and their theories are invariably extravagant. Vallancey may be regarded as the founder of a school of writers who theorise on Irish history, language, and literature, without having read the original chronicles, acquired the language, or studied the literature, and who have had some influence in retarding real studies, but have added nothing to knowledge. (Norman Moore)

Vallancey’s first offence was to assert that the ancestors of the Irish and the first inhabitants of Ireland were Phoenician colonists:

It is the opinion of many learned Irishmen, that some colony of the oriental people, who worshipped Belus, or Baal as the Chaldæans express it, gave its first inhabitants to this island. In all probability they were no other than the indigenæ of the Land of Promise, the CHANAANITES; who having been dispossessed by Joshua, and the people of Israel, made vast emigrations into the islands of the Mediterranean sea, and planted themselves not only in those islands, but also on the maritime

coasts and regions of that sea.

Instead of Chanaanites they then took the name of Phenicians, not from their dwelling at Tyre, Sidon, and the country near the Red Sea Φοινικος, or by allusion to the traffick of purple garments, or from the palm trees Φοινικις as different etymologists will have it; but rather from the Phenician word BEN-ANAK, the children or tribe of ANAK, the Anakites being the principal tribe of the whole, agreeable to the Irish tribes MAC-MAHON, MAC-CARTHY, &c. (Vallancey 2:58-59)

It is not my intention here to critique Vallancey’s theories, though I will make two points in his defence:

- The etymology of the ethnonym Phoenicians is still in dispute

- Phoenix was the name by which the Greeks referred to a mythical bird worshipped by the Egyptians as Bennu, so why should not the first part of Phoenician derive from the Phoenician word for son: ben?

Etymology and comparative linguistics were the lodestones that guided the majority of Vallancey’s speculations, and it is on these grounds that he is principally pilloried. These two are in evidence as far as his theories on Newgrange and its origins are concerned, but it is clear that he also relied upon what archaeologists today call comparative typology:

“We read in Eusebius,” says Porphyry, “that Zoroaster was the first who, having fixed upon a cavern in the mountains adjacent to Persia, formed the idea of consecrating it to MITHRA (the sun); that is to say, having made in this cavern several geometrical divisions, representing the seasons, the elements, he imitated, on a small scale, the order and disposition of the universe by Mithra. After Zoroaster, it became a custom to consecrate caverns for the celebration of mysteries.” “Such,” says Volney, “was the first projection of the sphere. Though the Persians give the honor of the invention to Zoroaster, it is doubtless due to the Egyptians.” (Volney’s Ruins, p. 297.)

“Such are the astronomical ornaments on the stones in the Mithratic cave of New Grange, a name corrupted evidently from Grian Uaigh, the cave of the sun. The engravings are a certain proof of the purpose for which it was constructed, and that it was not designed for a granary, or a Danish sepulchre, as has been asserted by a great pretender to a knowledge in Irish antiquities. (Vallancey 6:450-451)

The spread of Mithraism throughout the Roman Empire during the early centuries of the Common Era is well attested, so there is nothing far-fetched in the idea that it also became established in Ireland. This is a subject that modern scholarship has regretfully neglected. Vallancey, however, is almost certainly barking up the wrong tree if he thinks that the toponym New Grange is derived from the Irish words for sun (grian) and cave (uaigh) . There is no evidence that the place was called New Grange until the Cistercians of Mellifont Abbey incorporated it into their holdings as an agricultural demesne (a grange) sometime in the early fourteenth century (Father Colmcille 5, 8).

Taking Stock

It is instructive to pause here and see what modern scholarship has to say about the antiquaries of the eighteenth century:

Research over the following century was carried out in the shadow of Rowlands and Molyneux and those they inspired. Their influence can be seen in the writings of the members of the Dublin Physico-Historical Society, principally Charles Smith and Walter Harris, in those of the Englishman Thomas Wright, whose Louthiana was published in 1748, and in other writers of the middle decades of the century; indeed, it might well be said that this speculative and uncritical approach begun in the first decades of the eighteenth century, combined with the new ideals of Romanticism, was responsible for the excesses of the Collectanea de Rebus Hibernicis that saw its close. All the way through to the 1830s, writings on the megalithic tombs of Ireland are dominated by a non-archaeological approach. The spurious philology and etymology of Rowlands, whereby the origins and purpose of megalithic tombs were derived from the meanings and connections of their local names, in conjunction with an almost scholastic obsession with the writings of the ancients and those of modern authors from Rowlands onwards, stifled the ability of most to examine the monuments in the field afresh and without preconceptions. (McGuinness 81).

It is indeed a strange state of affairs when speculation that Newgrange was built by Danes or Druids is considered excessive. How, then, should we characterize the opinion of modern scholarship, which insists that the monument was actually built more than five thousand years ago by Neolithic farmers—farmers who then vanished into thin air, leaving nothing behind them but some rude edifices and a scattering of implements?

In fact, many of the early antiquarians who speculated on the origins of Newgrange did visit the mound and examine it for themselves. Naturally, they were influenced to some extent by what they read in the works of those who had preceded them. But the same can be said of today’s historians and archaeologists. Radiocarbon dates and peer-reviewed papers stifle the ability of most to examine the monuments in the field afresh and without preconceptions.

It is also unfair to blame these scholars for the flights of fancy of Charles Vallancey, whose Collectanea de Rebus Hibernicis (1770-1804) are held up by McGuinness as the natural culmination of eighteenth-century speculation. As far a Newgrange was concerned, Vallancey was an original thinker: he considered the mound a Mithratic cave (Vallancey 6:184) and derived its name from the Irish words for Sun (grian) and cave (uagh) (Vallancey 4:211). This is not remotely related to anything he might have read in the works of his most illustrious predecessors. Even Pownall, who believed that Phoenician migrants were responsible for many aspects of Celtic religion and civilization, never went so far as to suggest that these Phoenicians were the ancestors of the Celts, or that they constructed Newgrange.

To be continued ...

References

- Thomas Pownall, XXXV. A Description of the Sepulchral Monument at New Grange, near Drogheda, in the County of Meath, in Ireland. By Thomas Pownall, Esq; in a Letter to the Rev. Gregory Sharpe, D.D. Master of The Temple, The Society of Antiquaries of London, Volume 2, Issue 1 (January 1773)

- Thomas Molyneux, A Discourse Concerning the Danish Mounts, Forts and Towers in Ireland, George Grierson, Dublin (1725), Part III of Gerard Boate, A Natural History of Ireland in Three Parts, George & Alexander Ewing, Dublin (1726)

- Father Colmcille, An Important Mellifont Document, Journal of the County Louth Archaeological Society, Volume 14, Number 1 (1957), pp 1-13

- Edward Ledwich, The Antiquities of Ireland, john Jones, Dublin (1790, 1804)

- Rory Naismith, Martin Allen, Elina Screen (editors), Early Medieval Monetary History, Ashgate Publishing Limited, Farnham (2014)

- Charles Vallancey, Collectanea de Rebus Hibernicis, Volumes 1-6, Graisberry & Campbell, Dublin (1770-1804)

- David McGuinness, Edward Lhuyd’s Contribution to the Study of Irish Megalithic Tombs, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 126 (1996), pp 62-85

- Thomas Campbell, A Philosophical Survey of the South of Ireland in a Series of Letters to John Watkinson, M. D., London (1777)

- Henry Rowlands, Mona Antiqua Restaurata: An Archaeological Discourse on the Antiquities, Natural and Historical, of the Isle of Anglesey, the Antient Seat of the British Druids, Robert Owen, Dublin (1723)

- Jacob Des Moulins, Antiqua Restaurata: A Concise Historical Account of the Ancient Druids, Owen, London (1794)

- Walter Harris, The Whole Works of Sir James Ware Concerning Ireland, Revised and Improved, Volume II, Part I, The Antiquities of Ireland, S Powell, Dublin (1745)

- Thomas Wright, Louthiana: Or, An Introduction to the Antiquities of Ireland, W Faden, London (1748)

- Charles Smith, The Ancient and Present State of the County and City of Waterford, A Reilly, Dublin (1746)

Image Credits

- Newgrange: Photographic Unit of the Department of Environment, Heritage and Local Government, Fair Use

- Thomas Molyneux: Armagh County Museum, Public Domain

- Mona Antiqua Restaurata: Forgotten Books, Fair Use

- Thomas Wright: Wellcome Library, London, Creative Commons

- Charles Vallancey: Collectanea de Rebus Hibernicis, Volume VI (1804), Plate, Public Domain