“The question is not whether these experts are well trained. It is whether their world is predictable.” - Daniel Kahneman from Thinking, Fast and Slow

In my last TIL: Baby, did you forget to take your meds?, I wrote about the placebo effect and its powers.

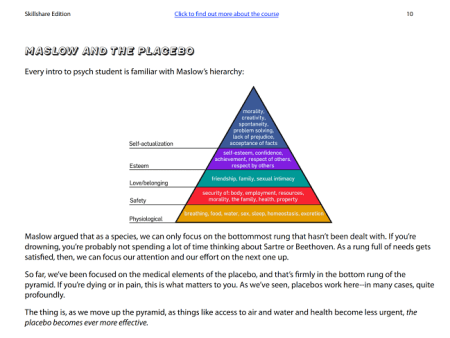

You don’t have to be a Sociologist or Psychologist to recognize this familiar graphic accompanying it:

Source

“The thing is, as we move up the pyramid, as things like access to air and water and health become less urgent, the placebo becomes ever more effective. Source

I am not sure about the frequency of the use of Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs, but I would guess it is included in upwards of 100% of marketing presentations.

Inspired by this I may make up a Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs Principle or Law or something…

But for now, take a look at this!

As I have described before, we all know about Godwin's law “asserting that ‘As an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Hitler approaches 1’ — that is, if an online discussion (regardless of topic or scope) goes on long enough, sooner or later someone will compare someone or something to Hitler.” Source

But to the best of my knowledge, which is limited in topic and scope, there is no “official” internet principle or law describing the Pavlov Psychology Principle.

Please leave a comment with a name suggestion or link to article of proof that this does exist already.

The Pavlov Psychology Principle is when any book in the field of Sociology, Psychology, or maybe just any academic circle eventually draws a link, parallel, or explanation of one topic to that famous Pavlov's Dog and Bell experiment that no one cares about except for the author and other future authors who are going to write about it because it is interesting, in theory.

Maybe it'sjust because we humans like dogs and therefore stories about dogs.

Many times life is just too mundane.

To combat our increasingly boring existences we scour the internet for something interesting.

And to hold our attention, authors, sometimes intentionally or perhaps inadvertently need to make the story a bit more fantastical to keep people from clicking away and bouncing somewhere else.

We know attention is valuable.

So should we be surprised to find the Pavlov Psychology Principle?

But you knew that right?

To not disappoint you, I will leave you this quote to answer the question:

“Many of us have the visceral memory of a single dubious dish that still leaves us vaguely reluctant to return to a restaurant. All of us tense up when we approach a spot in which an unpleasant event occurred, even when there is no reason to expect it to happen again. For me, one such place is the ramp leading to the San Francisco airport, where years ago a driver in the throes of road rage followed me from the freeway, rolled down his window, and hurled obscenities at me. I never knew what caused his hatred, but I remember his voice whenever I reach that point on my way to the airport.

My memory of the airport incident is conscious and it fully explains the emotion that comes with it. On many occasions, however, you may feel uneasy in a particular place or when someone uses a particular turn of phrase without having a conscious memory of the triggering event. In hindsight, you will label that unease an intuition if it is followed by a bad experience. This mode of emotional learning is closely related to what happened in Pavlov’s famous conditioning experiments, in which the dogs learned to recognize the sound of the bell as a signal that food was coming. What Pavlov’s dogs learned can be described as a learned hope. Learned fears are even more easily acquired.”

We find this quote deep within Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow.

Exibit 2: Influence: Science and Practice by Robert B. Cialdini

I wrote about the book here and here, but the point is that in Chapter 5 on Liking we find the Pavlov Psychology Principle.

In it Cialdini links to Pavlov in the following story:

“While politicians have long strained to associate themselves with the values of motherhood, country, and apple pie, it may be in the last of these connections—to food— that they have been most clever. For instance, it is White House tradition to try to sway the votes of balking legislators over a meal. It can be a picnic lunch, a sumptuous breakfast, or an elegant dinner; but when an important bill is up for grabs, out comes the silverware. Political fund-raising these days regularly involves the presentation of food. Notice, too, that at the typical fund-raising dinner the speeches and the appeals for further contributions and heightened effort never come before the meal is served, only during or after. There are several advantages to this technique. For example, time is saved and the reciprocity rule is engaged. The least recognized benefit, however, may be the one uncovered in research conducted in the 1930s by the distinguished psychologist Gregory Razran (1938).

Using what he termed the "luncheon technique," he found that his subjects become fonder of the people and things they experienced while they were eating. In the example most relevant for our purposes (Razran, 1940), subjects were presented with some political statements they had rated once before. At the end of the experiment, after all the political statements had been presented, Razran found that only certain of them had gained in approval—those that had been shown while food was being eaten. These changes in liking seem to have occurred unconsciously, since the subjects could not remember which of the statements they had seen while the food was being served.

How did Razran come up with the luncheon technique? What made him think it would work? The answer may lie in the dual scholarly roles he played during his career. Not only was he a respected independent researcher, he was also one of the earliest translators into English of the pioneering psychological literature of Russia. It was a literature dedicated to the study of the association principle and dominated by the thinking of a brilliant man, Ivan Pavlov.”

All this confirmation bias is tiring to amass, but there is still hope.

The more social proof we find of the Pavlov Psychology Principle, the more likely we are to be persuaded to believe it is real and not fake news.

Follow me @strangerarray and donate because of the Pavlov Psychology Principle.

Please check out my final Sunday Series post:

Or my recent TIL post:

Hey y’all for more great content check out my friends.

P.S. Before you go, do you have Student Loans and are looking for ways to save money?

I recommend Credible.

Use my link to get $200 !