Welcome back. This is part 2 of 2 from the Can you resist Persuasion Tactics? article which is part of the larger #persuasion series.

In fact, this Persuasion Series, as described in the introduction article Raise Your Steem Power Through Persuasion, is based on the Persuasion Reading List put together by Scott Adams.

You could read all these books yourself, but by up voting my articles you are outsourcing the hard part and getting all the good stuff filtered directly to you.

We continue with the dissection of Influence: Science and Practice Fourth Edition by Robert B. Cialdini

Notice Disclaimer: The images of the text and quotes are being used for educational purposes Mainly that of educating you on the benefits of using persuasion in your writing in the #steemitcommunity.

Picking up with Chapters 5 - 8:

Liking

>Phil: So what do we think of Ted and Linda kissing?

Lem: I'm for it. I like it when attractive people kiss.

Phil: Me, too. I like it when attractive people do anything. I was once knocked off my roller skates by a beautiful woman driving a bus. It was very pleasant.

> “Few of us would be surprised to learn that, as a rule, we most prefer to say yes to the requests of people we know and like. What might be startling to note, however, is that this simple rule is used in hundreds of ways by total strangers to get us to comply with their requests.” Influence, p. 144

The best example of how a sales professional uses liking is found in the story in Influence on pages 147-148:

> “There is a man in Detroit, Joe Girard, who specialized in using the liking rule to sell

Chevrolets. He became wealthy in the process, making over $200,000 a year.

> “ With such a salary, we might guess that he was a high-level GM executive or perhaps the owner of a Chevrolet dealership. But no. He made his money as a salesman on the showroom floor. He was phenomenal at what he did. For twelve years straight, he won the title of "Number One Car Salesman"; he averaged more than five cars and trucks sold every day he worked; and he has been called the world's "greatest car salesman" by the Guinness Book of World Records.”

> “For all his success, the formula he employed was surprisingly simple. It consisted of

offering people just two things: a fair price and someone they liked to buy from. "And

that's it," he claimed in an interview. "Finding the salesman you like, plus the price. Put

them both together, and you get a deal."”

> “Fine. The Joe Girard formula tells us how vital the liking rule is to his business, but it doesn't tell us nearly enough. For one thing, it doesn't tell us why customers liked him more than some other salesperson who offered a fair price.”

We find out why on page 152 of Influence:

>“Remember Joe Girard, the world's "greatest car salesman," who says the secret of his success was getting customers to like him? He did something that, on the face of it, seems foolish and costly. Each month he sent every one of his more than 13,000 former customers a holiday greeting card containing a printed message. The holiday greeting card changed from month to month (Happy New Year, Happy Valentine's Day, Happy Thanksgiving, and so on), but the message printed on the face of the card never varied. It read, "I like you." As Joe explained it, "There's nothing else on the card, nothin' but my name. I'm just telling 'em that I like 'em."”

> “"I like you." It came in the mail every year, 12 times a year, like clockwork. "I like you," on a printed card that went to 13,000 other people, too. Could a statement of liking so impersonal, obviously designed to sell cars, really work: Joe Girard thought so, and a man as successful as he was at what he did deserves our attention.”

To resist this desire to automatically agree with people you like or who have made it possible for you to think you like them, the clue is in Influence on page 174:

> “It would be pointless to construct a horde of specific countertactics to combat each of the countless versions of the various ways to influence liking.”

> “Instead we need to consider a general approach, one that can be applied to any of the liking-related factors to neutralize their unwelcome influence on our compliance decisions. The secret to such an approach may lie in its timing. Rather than trying to recognize and prevent the action of liking factors before they have a chance to work on us, we might be well advised to let them work. Our vigilance should be directed not toward the things that may produce undue liking for a compliance practitioner but toward the fact that undue liking has been produced. The time to call out the defense is when we feel ourselves liking the practitioner more than we should under the circumstances.”

That is some powerful persuasion. You can use that to gain #SteemPower by taking part in the #steemitcommunity by writing likeable articles, actively engaging with other post through replies, and up voting this post, like you have considered doing, and because you are committed you probably should.

Authority

Did you read this after the author @strangerarray told you not to?

And then insulted you for having authority issues?

Well if so, my sincere apologies. I don’t know you so I should diagnosis your problems. I only know my own and authority issues come up from time to time…

The most powerful example of Authority given in Influence is that of the Milgram study, known to us students of #psychology.

Briefly, Professor Stanley Milgram created a study on how people respond to authority when given orders that may be harmful to other humans. The participant was brought in and told to administer a shock when the “tester” got the wrong answer. However, the “tester” was an actor in on the experiment and was told to miss questions and then plead for the shocks to desist.

Instead of stopping when the “tester” pleaded for mercy, the participant continued to give the shocks (which where fake) until the highest voltage on the experiment was reached.

The footnote number 2 on page 184 of Influence had this to say about it:

> “In fact, Milgram first began his investigations in an attempt to understand how the German citizenry could have participated in the concentration camp destruction of millions of innocents during the years of Nazi ascendancy. After testing his experimental procedures in the United States, he had planned to take them to Germany, a country whose populace he was sure would provide enough obedience for a full-flown scientific analysis of the concept. The first eye-opening experiment in New Haven, Connecticut, however, made it clear that he could save his money and stay close to home. "I found so much obedience," he said, "I hardly saw the need of taking the experiment to Germany."”

> “These results surprised everyone associated with the project, Milgram included.” Influence, p. 181

> “The basic experiment, as well as all these and other variations on it, is presented in Milgram's highly readable Obedience to Authority, 1974.” Influence, p. 183

Another, more funny example, of Authority comes in the story of “just following orders” of Doctors.

And you thought people were rational…

The defense speaks in Influence page 196:

> “One protective tactic we can use against authority status is to remove its element of surprise. Because we typically misperceive the profound impact of authority (and its symbols) on our actions, we become insufficiently cautious about its presence in compliance situations. A fundamental form of defense against this problem, therefore, is a heightened awareness of authority power. When this awareness is coupled with a recognition of how easily authority symbols can be faked, the benefit will be a properly guarded approach to situations involving authority influence attempts.

> “Sounds simple, right? And in a way it is. A better understanding of the workings of authority influence should help us resist it. Yet, there is a perverse complication— the familiar one inherent in all weapons of influence: We shouldn't want to resist authority altogether or even most of the time. Generally, authority figures know what they are talking about. Physicians, judges, corporate executives, legislative leaders, and the like have typically gained their positions through superior knowledge and judgment. Thus, as a rule, their directives offer excellent counsel.”

> “Authorities, then, are frequently experts; indeed, one dictionary definition of an authority is an expert. In most cases, it would be foolish to try to substitute our less informed judgments for those of an expert, an authority. At the same time, we have seen in settings ranging from street corners to hospitals that it would be foolish to rely on authority direction in all cases. The trick is to be able to recognize without much strain or vigilance when authority directives are best followed and when they are not.”

Up vote this post now, the author said so

Scarcity

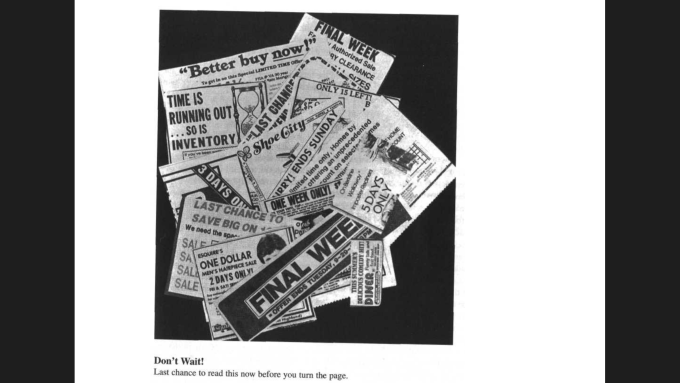

We have all seen this persuasion tactic used in commercials, online ads, and sales copy.

Limited time only

Get it now before it’s gone

Up vote this article now before time runs out

Influence p. 209

Influence p. 209

> “People seem to be more motivated by the thought of losing something than by the thought of gaining something of equal value.”

Influence p. 205

This chapter has a great example about an experiment involving cookies but it is a bit laborious and drawn out so I will give you the results and then a different story that is more entertaining.

> “As we might expect from the scarcity principle, when the cookie was one of only two available, it was rated more favorably than when it was one of ten. The cookie in short supply was rated as more desirable to eat in the future, more attractive as a consumer item, and more costly than the identical cookie in abundant supply.” Influence p. 219

However:

> “Even though the scarce cookies were rated as significantly more desirable, they were not rated as any better-tasting than the abundant cookies. So, despite the increased yearning that scarcity caused (the raters said they wanted to have more of the scarce cookies in the future and would pay a greater price for them), it did not make the cookies taste one whit better. Therein lies an important insight. The joy is not in the experiencing of a scarce commodity but in the possessing of it. It is important that we not confuse the two.” Influence p. 228

Also scarcity is the reason we have authority issues as mentioned at the start of this article.

> “As opportunities become less available, we lose freedoms. And we hate to lose the freedoms we already have. This desire to preserve our established prerogatives is the centerpiece of psychological reactance theory, developed by psychologist Jack Brehm to explain the human response to diminishing personal control '. W. Brehm, 1966; S. S. Brehm & J. W. Brehm, 1981). According to the theory whenever free choice is limited or threatened, the need to retain our freedoms makes us want them (as well as the goods and services associated with them) significantly more than before. Therefore, when increasing scarcity-or anything else—interferes with our prior access to some item, we will react against the interference by wanting and trying to possess the item more than we did before.” Influence pp. 208-209

This is why if we are told something, we have the desire to do the opposite.

Being told what to do is a limitation on our freedom of choice. As a reaction, reactance, we decide we don’t like the limitation and instead do the opposite in a proof that we do have freedom. In kids this behavior is frustrating to parents, as adults, its par for the course.

The second promised example story is about scarcity and selling cars:

> The author, Robert Cialini’s “brother Richard supported himself through school by employing a compliance trick that cashed in handsomely on the tendency of most people to miss that simple point. In fact, his tactic was so effective in this regard that he had to work only a few hours each weekend for his money, leaving the rest of the time free for his studies.”

> “Richard sold cars, but not in a showroom or on a car lot. He would buy a couple of used cars sold privately through the newspaper on one weekend, and adding nothing but soap and water, would sell them at a decided profit through the newspaper on the following weekend. To do this, he had to know three things. First, he had to know enough about cars to buy those that were offered for sale at the bottom of their blue book price range but that could be legitimately resold for a higher price. Second, once he got the car, he had to know how to write a newspaper ad that would stimulate substantial buyer interest. Third, once a buyer arrived, he had to know how to use the scarcity principle to generate more desire for the car than it perhaps deserved. Richard knew how to do all three. For our purposes, though, we need to examine his craft with just the third.”

> “For a car he had purchased on the prior weekend, he would place an ad in the Sunday paper. Because he knew how to write a good ad, he usually received an array of calls from potential buyers on Sunday morning. Each prospect who was interested enough to want to see the car was given an appointment time— the same appointment time. So, if six people were scheduled, they were all scheduled for, say, 2:00 that afternoon. This little device of simultaneous scheduling paved the way for later compliance because it created an atmosphere of competition for a limited resource.”

> “Typically, the first prospect to arrive would begin a studied examination of the car and would engage in standard car-buying behavior, such as pointing out any blemishes or deficiencies and asking if the price were negotiable. The psychology of the situation changed radically, however, when the second buyer drove up. The availability of the car to either prospect suddenly became limited by the presence of the other. Often the earlier arrival, inadvertently stoking the sense of rivalry, would assert his right to primary consideration. "Just a minute now, I was here first." If he didn't assert that right, Richard would do it for him. Addressing the second buyer, he would say, "Excuse me, but this other gentleman was here before you. So, can I ask you to wait on the other side of the driveway for a few minutes until he's finished looking at the car? Then, if he decides he doesn't want it or if he can't make up his mind, I'll show it to you."”

> “Richard claims it was possible to watch the agitation grow on the first buyer's face. His leisurely assessment of the car's pros and cons had suddenly become a now-or-never, limited-time-only rush to a decision over a contested resource. If he didn't decide for the car—at Richard's asking price—in the next few minutes, he might lose it for good to that... that. .. lurking newcomer over there. The second buyer would be equally agitated by the combination of rivalry and restricted availability. He would pace about the periphery of things, visibly straining to get at this suddenly more desirable hunk of metal. Should 2:00 appointment number one fail to buy or even fail to decide quickly enough, 2:00 appointment number two was ready to pounce.”

> “If these conditions alone were not enough to secure a favorable purchase decision immediately, the trap snapped securely shut as soon as the third 2:00 appointment arrived on the scene. According to Richard, stacked-up competition was usually too much for the first prospect to bear. He would end the pressure quickly by either agreeing to Richard's price or by leaving abruptly. In the latter instance, the second arrival would strike at the chance to buy out of a sense of relief coupled with a new feeling of rivalry with that... that... lurking newcomer over there.”

> “All those buyers who contributed to my brother's college education failed to recognize a fundamental fact about their purchases: The increased desire that spurred them to buy had little to do with the merits of the car. The failure of recognition occurred for two reasons. First, the situation that Richard arranged for them produced an emotional reaction that made it difficult for them to think straight. Second, as a consequence, they never stopped to think that the reason they wanted the car in the first place was to use it, not merely to have it. The competition-for-a-scarce-resource pressures Richard applied affected only their desire to have the car in the sense of possessing it. Those pressures did not affect the value of the car in terms of the real purpose for which they had wanted it.” Influence pp. 229-230

The Defense Against Scarcity Persuasion

> “Here's our predicament, then: Knowing the causes and workings of scarcity pressures may not be sufficient to protect us from them because knowing is a cognitive act, and cognitive processes are suppressed by our emotional reaction to scarcity pressures. In fact, this may be the reason for the great effectiveness of scarcity tactics. When they are employed properly, our first line of defense against foolish behavior—a thoughtful analysis of the situation—becomes less likely.” Influence p. 228

> “Whenever we confront the scarcity pressures surrounding some item, we must also confront the question of what it is we want from the item. If the answer is that we want the thing for the social, economic, or psychological benefits of possessing something rare, then, fine; scarcity pressures will give us a good indication of how much we would want to pay for it—the less available it is, the more valuable to us it will be. However, very often we don't want a thing for the pure sake of owning it. We want it, instead, for its utility value; we want to eat it or drink it or touch it or hear it or drive it or otherwise use it. In such cases it is vital to remember that scarce things do not taste or feel or sound or ride or work any better because of their limited availability.” Influence pp. 228-229

As with most of these persuasion tactics, we don’t necessarily want to avoid them at all cost. We just want to be aware of what is happening so we can be better prepared for what follows.

When writing articles or post on #steemit, you will want to have a persuasive tone to induce readers to up vote your articles and thereby increasing your Steem Power.

Instant Influence

This last chapter is a summary of what we have covered in this enlightening book.

In Summary:

> “Very often when we make a decision about someone or something we don't use all of the relevant available information. We use, instead, only a single, highly representative piece of the total. An isolated piece of information, even though it normally counsels us correctly, can lead us to clearly stupid mistakes—mistakes that, when exploited by clever others, leave us looking silly or worse.” Influence p. 234

> “Despite the susceptibility to stupid decisions that accompanies a reliance on a single feature of the available data, the pace of modern life demands that we frequently use this shortcut.” Influence p. 234

> “John Stuart Mill, the British economist, political thinker, and philosopher of science, died over 125 years ago. The year of his death (1873) is important because he is reputed to have been the last man to know everything there was to know in the world. Today, the notion that one of us could be aware of all known facts is laughable. After eons of slow accumulation, human knowledge has snowballed into an era of momentum-fed, multiplicative, monstrous expansion. We now live in a world where most of the information is less than 15 years old. In certain fields of science alone (physics, for example), knowledge is said to double every eight years. The scientific information explosion is not limited to such arcane arenas as molecular chemistry or quantum physics, but extends to everyday areas of knowledge where we strive to keep ourselves current—health, child development, nutrition. What's more, this rapid growth is likely to continue, since researchers are pumping their newest findings into an estimated 400,000 scientific journals worldwide.” Influence p. 236

And with steemit.com the rate of information shared is only getting more and faster, because of this you should up vote this article to help others benefit from the lessons on #persuasion

> “When those single features are truly reliable, there is nothing inherently wrong with the shortcut approach of narrowed attention and automatic responding to a particular piece of information. The problem comes when something causes the normally trustworthy cues to counsel us poorly, to lead us to erroneous actions and wrongheaded decisions. As we have seen, one such cause is the trickery of certain compliance practitioners, who seek to profit from the mindless and mechanical nature of shortcut responding. If, as it seems, the frequency of shortcut responding is increasing with the pace and form of modern life, we can be sure that the frequency of this trickery is destined to increase as well.”

> “What can we do about the expected intensified attack on our system of shortcuts? More than evasive action, I urge forceful counterassault; however, there is an important qualification. Compliance professionals who play fairly by the rules of shortcut responding are not to be considered the enemy; to the contrary, they are our allies in an efficient and adaptive process of exchange. The proper targets for counter-aggression are only those individuals who falsify, counterfeit, or misrepresent the evidence that naturally cues our shortcut responses.” Influence p. 238

There you have it folks. A vision of the powers of #influence and #persuasion and how you can use them both for good or for bad.

The power is yours. Choose wisely.

Check back for more on this series on #persuasion

Because you never know who you are going to meet…

@strangerarray

The guide:

*Introduction to Persuasion Series

*First Flight: Imagination and Persuasion

*Illusions: The Adventures of a Reluctant Messiah

*Influence by Robert B. Cialdini -- Part 1

*Influence -- Part 2: Resistance to Persuasion is Futile. Part 2 of 2

*Coming Soon…. How to Fail at Almost Everything and Still Win Big by Scott Adams