- How Old Is Newgrange? (Part 3)

Newgrange in the 19th Century

In the early 19th century, scholarship was primarily concerned with establishing the identity of the architects of Newgrange. Was the monument constructed by foreign invaders—Danes, for instance—or was it of native origin? The age of the monument was a secondary issue, though we do begin to detect a nascent tendency to push the date of construction into the remote past.

Three Irish scholars, George Petrie, John O’Donovan and Eugene Curry, spearheaded the campaign to reclaim Newgrange and other megalithic structures for the natives. They were not, however, the first antiquaries of the century to attribute the megaliths to the Celts.

In 1806, during his tour of Ireland, the English antiquary and pioneering archaeologist Richard Colt Hoare visited Newgrange. He noted a great similarity between the markings that were incised on stones at Newgrange and ornaments he had observed on ancient British urns recovered from beneath tumuli in Wiltshire, England.

I am inclined therefore to attribute this singular temple to some of the Celtic, or Belgic tribes, who poured in upon us from the Continent of Gaul, and peopled England, together with Wales, Scotland. and Ireland. (Hoare 256)

George Petrie

The polymath George Petrie pleaded his case for Newgrange with an impassioned article in the Dublin Penny Journal in 1833:

If England may justly boast of her Stonehenge as the noblest monument of its kind now existing, Ireland can, with equal reason, feel proud of the sepulchral tumulus of New Grange—a monument of human labour only exceeded in grandeur by the tomb of Agamemnon, at Mycenæ, or the pyramids of the Egyptian Kings, to both of which it is so nearly allied in many of its general features and which, in point of antiquity it probably rivals, or even possibly exceeds!

The tumulus of New Grange, is one of the four great sepulchral mounds, situate on the banks of the Boyne, between Drogheda and Slane, in the county of Meath, and which we will not hesitate to say may justly be termed the Pyramids of Ireland...

This most ancient, and, though rude, most magnificent monument, has been described and illustrated by Molyneaux [sic], Harris, Pownall and Ledwich, all of whom, unwilling, apparently, to allow the ancient Irish the honor of erecting a work of such vast labour and grandeur, concur in ascribing it to the piratical Danes, who infested the island in the 9th and 10th centuries. We are well aware that the Danes as well as all the other branches of the great Scythian stock, raised large sepulchral Mounds; but where in the north of Europe does there exist a monument of the kind, to rival this and its companions, on the Boyne? And is it likely that Danish colonies, in a country in which they had never a secure settlement, would raise monuments exceeding in grandeur any which existed in their own country? Or if they might, is it to be believed that tradition would be silent, or that our annals, which are so minute in recording the works as well as deeds of those lawless robbers would preserve no memorial of so vast a labour? No! It is to the anciently civilized south of Europe, not the barbarous north, that we must look for the prototypes of those grand monuments of the dead; which, equally, with the brazen weapons and vessels, the cyclopean forts, and other remains, identify the ancient inhabitants of Ireland with the most ancient Egyptians and the Greeks of the heroic times. The arguments of those learned men above alluded to in support of their hypothesis, are puerile, and scarcely deserve serious notice; we are not without historic evidence to prove that the Danes, so far from being the erectors of the monuments on the Boyne, were as might be more rationally expected, their destroying plunderers. (Petrie 305-306)

Petrie did not tell his readers how old he thought the pyramids of Egypt were or why he thought that Newgrange was probably as old as them or even possibly older than them. In 1798, on the morning of the Battle of the Pyramids, Napoleon Bonaparte allegedly pointed to the pyramids of Giza and exhorted his troops with the words:

Songez que du haut de ces pyramides quarante siècles vous contemplent [Remember that from those monuments forty centuries look down upon you.] (Beauharnais 41)

This would date the pyramids to about 2200 BCE.

John O’Donovan

John O’Donovan, a native of Kilkenny, researched toponyms, or place names, for the Ordnance Survey of Ireland from 1830 to 1842. For most of this period the Survey’s Topographical Department—which included the antiquities division—was headed by Petrie. In 1836, while O’Donovan was researching place names in County Meath, he recorded some opinions on the identity and location of Brugh na Bóinne in his letters to the Superintendent of the Ordnance Survey Thomas A Larcom:

August 8 ... Brugh na Boinne, a famous pagan burial ground, lies between Slane and Stackallan ... August 15th ... Today I shall collect all the evidences which convince me that the place now called Broad Boyne and Bray Bridge near Stackallan is the Brugh na Boinne (Brū na Bōniă) of the ancient writers (O’Donovan 317 ... 319 ... 327 ... 327)

The townland of Stackallan, or Broad Boyne, lies on the River Boyne about 9-10 km west of Newgrange. There are megalithic structures still extant in this area: Ardmulchan Passage Tomb on the south side of the Boyne is the most notable. O’Donovan was satisfied that Broad Boyne represented a most probable Anglicising of Brugh na Bóinne.

In another letter, dated 21 August 1836, O’Donovan recounted his attempts to locate a royal abode known in the written tradition as The House of Cletty. He was satisfied that it was in the immediate vicinity of Brugh na Boinne (O’Donovan 445):

I travelled last Saturday along the banks of the Boyne to see if I could discover any fort which I could set down as the site of the house of Cletty, but I found nothing unless it be one of the forts on the south side of the River at Broad-Boyne Bridge. If this fort be the house of Cletty, the Pagan Cemetery of Brugh na Boinne must have been on the other side of the river... (O’Donovan 446)

This contradicts his opinion of 8 August that the House of Cletty was on the north side of the river and Brugh na Bóinne on the south. In a letter to Larcom dated 15 August, O’Donovan (327-340) enumerated several pieces of evidence in support of his identification:

Similarity of name: Broad Boyne is probably an Anglicisation of Brugh na Boinne.

A tradition in the west of Meath that Brugh na Boinne is immediately at Stackallan Bridge.

The ford at Stackallan Bridge (Broadboyne Bridge) was anciently known as Aṫ an ḃróġa, the ford of the Brugh.

A tradition that when the body of King Cormac Mac Airt was being carried across the Boyne to be buried at Brugh na Bóinne, it fell into the river and was washed downstream to Rosnaree, which is about 1 km upstream (west) of Newgrange.

Each of these points can be contested, though not necessarily refuted.

Broad Boyne may simply be an English name for the region where the river broadens.

Stackallan Bridge was only built around 1820, so just how trustworthy is a tradition that links its location to Brugh na Bóinne?

If the pagan kings of Tara were buried in Newgrange, the ford at Stackallan would have been the obvious place to transport their bodies across the Boyne, so it would not be surprising if it came to be known as the ford of the Brugh. It is possible that the principal northbound highway from Tara, the Slige Midluachra, actually crossed the Boyne at this ford, which was called Brow Ford (Smith 70)—though this is disputed by other sources, which place Brow Ford just below Newgrange (Stout 18).

Similarly, if Cormac’s body fell into the Boyne as it was being carried to Newgrange, this would have happened at Brow Ford, so it would not be surprising if his body was washed ashore at Rosnaree, downstream of the ford but upstream of Newgrange. This also supports O’Donovan’s location of Brow Ford at Stackallan.

Such was John O’Donovan’s standing as a scholar that his identification of Brugh na Bóinne with Broad Boyne survived well into the following century. In a paper read to the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland in 1919, the President Thomas Johnson Westropp was obliged to include the following cautionary remarks:

The unfounded identification of Brugh na Boinne with “Broad Boyne” (or Stackallen) has no adherent of any standing, but is not extinct. The survival of the name (traceable to 1541 in various documents) at Bro House near Newgrange and the proof that Knowth (Cnogba) was at Brugh in the Dind Senchas of Nás are strongly corroborative. (Westropp 7)

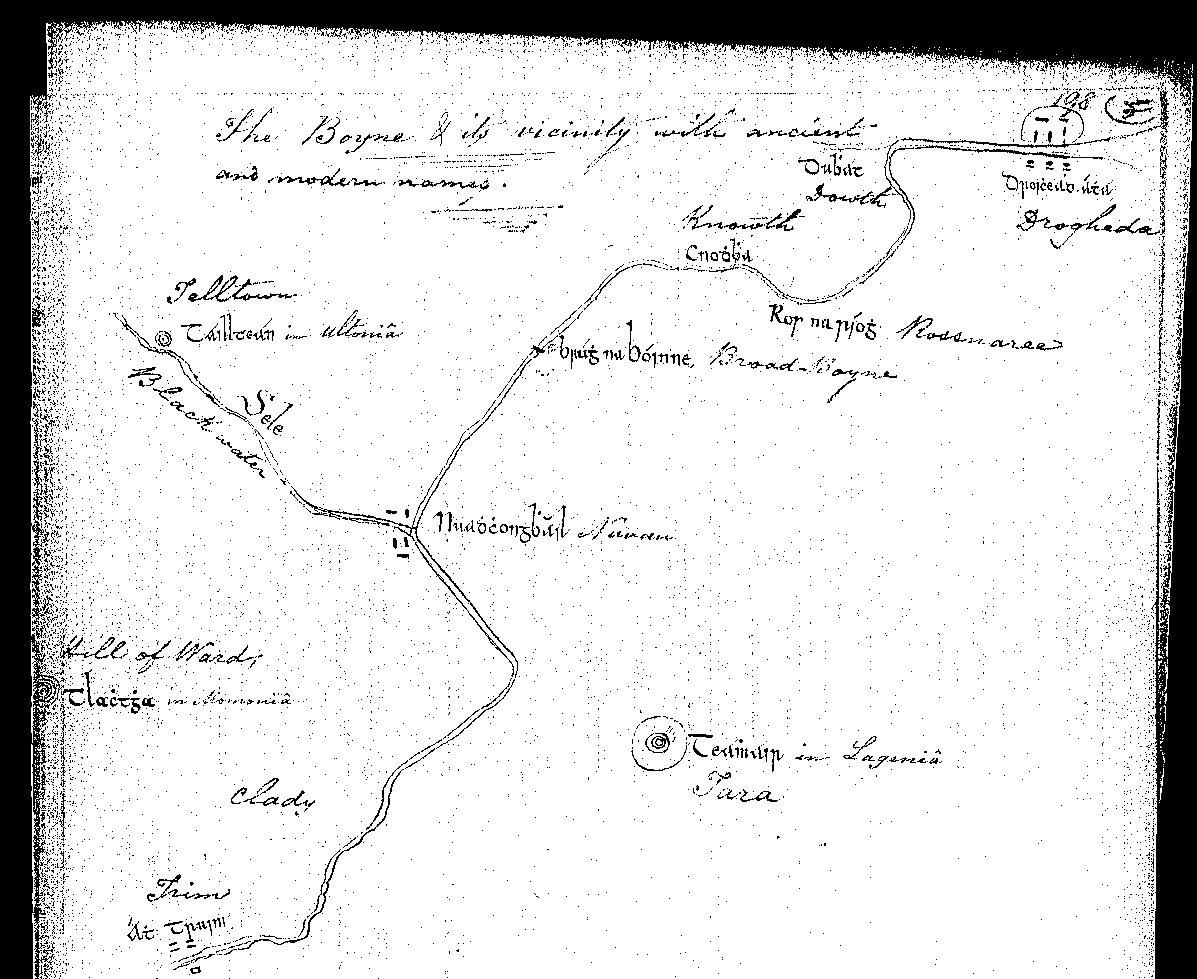

All of this raises the question: If John O’Donovan did not identify Newgrange with Brugh na Bóinne, what did he identify it with? What, in his opinion, was the traditional Irish name for Newgrange? Siodh an Bhrugh, perhaps? I do not know if he ever answered this question. Curiously, his sketch of the Boyne and its vicinity includes Knowth and Dowth, but it omits Newgrange altogether.

John O’Donovan was one of Ireland’s finest scholars, but his identification of Brugh na Bóinne with Broadboyne or Stackallan has few adherents today. Perhaps it deserves a second look, bearing in mind the reputation of the man who proposed it and the cogency of the arguments with which he defended it.

William Wilde

William Wilde, surgeon, antiquary and the father of Oscar Wilde, was largely responsible for rolling back O’Donovan’s identification and establishing the still popular idea that Brugh na Bóinne referred not to Newgrange specifically but to the entire Boyne Valley complex of sepulchral mounds, of which Newgrange, Knowth and Dowth are the largest. His travel book The Beauties of the Boyne, and its Tributary, the Blackwater, included a lengthy description of the Boyne Valley megaliths. Before dealing with Brugh na Boinne, however, he took issue with O’Donovan’s identification:

The broad reach of the river below the bridge at Stackallan has been supposed by some antiquarians to be in the vicinity of Brugh-na-Boinne, one, if not the chief of the royal cemeteries, and where the monarchs of Tara were interred of old; but we think that the evidence is in favour of a locality lower down beyond Slane. A deep pool, immediately below the bridge, receives the name of Lugaree, the king’s hole, where the river well deserves the name of the “Broad Boyne,” which it still retains. (Wilde 169)

In Chapter VIII, The Royal Cemetery at Brugh-na-Boinne, Wilde wrote:

But by far the most celebrated and extensive of all the Irish cemeteries was that denominated Brugh, or Brugh na Boinne, the Burgum Boinne, the fort or town of the Boyne ... This was the great royal cemetery of the Kings of Tara; and from an examination of the various authorities which describe it, as well as the monuments themselves which still exist, it is manifest that Brugh na Boinne was no other than the assemblage of mounds, caves, pillar-stones, and other sepulchral monuments, forming the great necropolis which extends along the left or northern bank of the river, from Slane to Netterville. (Wilde 184)

If Brugh na Bóinne referred to the entire complex, what name denoted Newgrange alone? Wilde offered several suggestions:

... in an ancient MS in the Library of Trinity College, Dublin, called “Irish Triads,” enumerating three of each of the most remarkable objects in Erin—as the three mountains, the three cataracts, the three plains, and the three rivers—it is stated that the three darkest caves of Ireland are Uaimh Cruachna, i.e. the cave of Croghan; Uaimh Slaine, i.e. the cave or crypt of Slane; and Dearc Fearna, i.e. the cave of Dunmore, near Kilkenny ... Can New Grange be the cave of Slane? (Wilde 180)

The Dagda, whose monument is enumerated in this cemetery, was a king of the Tuatha De Danaans, named Eachaidh Ollathair, whose reign for eighty years, commenced (it is said in the annals) at the year of the world 3371. He was styled Daghda-mor, the “Great Good Fire,” from his military ardour; and his monument in the cemetery of the Boyne was called Sidh-an-Brogha. May it not be one of those great sepulchral mounds now in sight, which we are about to describe? (Wilde 188)

... and although New Grange (which, as already stated, is a mere modern name, which gives no reference either to its use or locality) is not specified, it may fairly be inferred that it formed one of the group of the Boyne pyramids rifled by the plundering Northmen, AD 862. “The cave of Achadh Aldai, and of Cnodhba (Knowth), and the cave of the sepulchre of Boadan, over Dubhad (Dowth), and the cave of the wife of Gobhan (at Drogheda), w[ere] searched by the Danes” ... All these sepulchres were in one territory, the land of Flann, son of Conang, one of the chieftains of Meath; and, in all probability, the cave of Achadh Aldai—that is, the field of Aldai, the ancestor of the Tuatha De Danaan kings—is that which is now known as New Grange? (Wilde 202-203)

Although Wilde took issue with O’Donovan’s location of Brugh na Bóinne, he was in agreement with him and his colleagues that Newgrange was a native monument of great age:

How far anterior to the Christian era its date should be placed, would be a matter of speculation; it may be of an age coeval, or even anterior, to its brethren on the Nile. (Wilde 203)

Eugene O’Curry

In 1835 the Irish antiquary and philologist Eugene O’Curry was recruited to the Ordnance Survey at the recommendation of John O’Donovan. He was Professor of Irish History and Archaeology at the Catholic University of Ireland from its foundation in 1854. His lectures, which were subsequently published by the University and are now available online, are an important source for early Irish history. They also make fascinating reading for anyone interested in the evolution of Irish historiography.

I do not know if O’Curry ever committed himself on the question of the identification of Brugh na Bóinne. As he owed his position in the Ordnance Survey to John O’Donovan, it is possible—if not probable—that he deferred to O’Donovan’s opinion that Brugh na Bóinne was at Broad Boyne. In a lecture he delivered in the 1850s, he discussed

A poem of thirteen stanzas, or fifty-two lines, on Brugh-Mic-an-Oig (the ancient Tuatha Dé Danann Palace, on the Boyne, near Slane. (O’Curry 106)

Slane is approximately halfway between Newgrange and Broad Boyne, so no conclusion can be drawn from this remark, which seems to be the closest O’Curry ever came to fixing the location of the Brugh.

As far as the origins of Newgrange are concerned, O’Curry was also silent, but in his lectures he always associated Ireland’s megalithic structures with her native races, such as the Tuatha Dé Danann, the Fir Bolg and the Milesians.

James O’Laverty

The Reverend James O’Laverty was a member of the Royal Irish Academy and a native of County Down. He is best remembered for his history of the Diocese of Down and Connor, the first volume of which appeared in 1878. About twenty years earlier he had visited Newgrange, where he had made an interesting discovery:

Having frequently observed that when English names had been imposed on townlands, the old Irish name still lingered as a denomination for some hill or place in the townland, I trusted that the monument of the Dagda and the pagan Kings of Tara [ie Newgrange], which is little less wondrous than the Pyramids of Egypt, had not altogether renounced its ancient name. It is now more than thirty years since I went to Newgrange for the special purpose of investigating that matter. I explained to Mr. Maguire, then of Newgrange, and to his son, that Brugh-na-Boinne signified “the town, or dwelling-place, on the Boyne,” that the word Brugh would assume the modern form Bro, as in Brughshane (pronounced Broshane), and many other townland names, and that na-Boinne, “of the Boyne,” would probably cease to be used as unnecessary at the site. I need not say that I was greatly pleased when they informed me that the field in which is the mound of Newgrange is called the Bro-Park while in the immediate vicinity are the Bro-Farm, the Bro-Mill, and the Bro- Cottage. Thus, the identical name “the Brugh,” by which the celebrated place is called in the Senchus-na-Relec (History of Cemeteries), though unobserved by the learned, still lingers around the monument of the Danaans. (O’Laverty 430)

Although not published until 1892, O’Laverty’s observations were originally made around 1860 and were alluded to by Anthony Cogan in his history of the Diocese of Meath of 1867:

It appears to the author of this work, that Dr. Wilde (now Sir William) has satisfactorily proved that the present mounds of Knowth, Dowth, and Newgrange, were the ancient Brugh-na-Boinne, the chief royal cemet[e]ry in pagan times of the kings of Tara—(See Boyne and Blackwater, chap. viii; also Diocese of Meath, vol. i. p. 3.) It would seem that at an early period the name was changed by the Anglo-Norman settlers to that of Newgrange, and thus, in process of time, the old name was lost sight of. However, what strongly confirms all Dr. Wilde has written is the fact that the farm adjoining Newgrange is to this day called the Bro farm, and even a mill in the neighbourhood is called by the peasantry the mill of the Bro. Thus, in a corrupted and an abbreviated form, the old name Brugh-na-Boinne has lingered in the neighbourhood unobserved, and thus has escaped the attention of the learned. The notice of the author was first called to this circumstance by the Rev. James O’Laverty, Dean of St. Malachy’s Seminary, Belfast, and to him he wishes to accord the merit of the discovery. (Cogan 307 fn)

For most historians and antiquarians, O’Laverty’s evidence sounded the death-knell of O’Donovan’s Broadboyne theory.

Taking Stock

The nineteenth century marked an important watershed in the study of Irish antiquities, including Newgrange. The first six or seven decades of the century saw the decline of the Danish theory—which attributed most of the country’s megalithic structures to Scandinavian colonists of the ninth and tenth centuries—and the championing of the native Irish as the true megalith-builders. Far from having been constructed by the Danes, Newgrange was now regarded as one of the native monuments that the Norsemen ransacked in search of treasure.

We also saw that at least two nineteenth-century scholars—Petrie and Wilde—speculated that Newgrange might be older than the pyramids of Giza, but neither of them offered the slightest piece of evidence in support of this suggestion, or even attempted to date the pyramids. It was as though the idea was simply plucked from the air.

I end this article with some wise remarks that John O’Donovan appended to the letter in which he defended his identification of Brugh na Bóinne with Broad Boyne:

We, in Irish antiquarian research, like Lord Bacon in natural philosophy, shall have to strike out new modes of investigation. We must pursue the inductive system, that is, first amass a large collection of facts, and then draw such conclusions as these facts will warrant. Truth will never be illustrated in any other way. (O’Donovan 341)

To be continued ...

References

- Eugène de Beauharnais, Memoires Et Correspondance Politique Et Militaire Du Prince Eugène de Beauharnais, tome Premier, Michel Lévy Frères, Paris (1858)

- Anthony Cogan, The Diocese of Meath: Ancient and Modern, Volume II, Joseph Dollard, Dublin (1867)

- Richard Colt Hoare, Journal of A Tour in Ireland, A. D. 1806, W Miller, London (1807)

- Eugene O’Curry, Manners and Customs of the Ancient Irish, Volume II, W B Kelly, Dublin (1873)

- John O’Donovan, Ordnance Survey of Ireland: Letters, Meath, 14 E 2/33, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin

- James O’Laverty, “Newgrange Still Called by Its Ancient Name, Brugh-na-Boinne,” The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Fifth, Volume 2.4 (1892)

- George Petrie, New Grange, Dublin Penny Journal, Volume 1, Number 39, 23 March 1833, pp 305-306

- Jessica Smith (compiler and editor), Brú na Bóinne World Heritage Site: Research Framework, An Chomhairle Oidhreachta/The Heritage Council, Dublin (2009)

- Geraldine Stout, Newgrange and the Bend of the Boyne, Cork University Press, Cork (2002)

- Thomas Johnson Westropp, The Ancient Places of Assembly in the Counties Limerick and Clare, Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, For the Year 1919, Volume 49, Part 1, Hodges, Figgis & Company, Dublin (1919)

- William R Wilde, The Beauties of the Boyne, and its Tributary, the Blackwater, James McGlashan, Dublin (1849)

Image Credits

- Newgrange: Wikimedia Commons, Copyright Dave Keeshan, Creative Commons

- George Petrie: Wikipedia, Public Domain

- John O’Donovan: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

- Broadboyne Bridge: Copyright JP, Creative Commons

- Eugene O’Curry: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

- James O’Laverty: O’Laverty Library, Public Domain