- How Old Is Newgrange? (Part 5)

Newgrange Is Taken into Care

In 1882 the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland passed into law the Ancient Monuments Protection Act, which placed sixty-eight historic sites in these islands under State protection. This Act provided for the appointment of Commissioners of Works as guardians of these sites. These Commissioners were given the power to purchase monuments covered by the Act and to appoint inspectors to examine these monuments and advise the Commissioners on the best means of maintaining and preserving them:

The expressions “maintain” and “maintenance” include the fencing, repairing, cleansing, covering in, or doing any other act or thing which may be required for the purpose of repairing any monument or protecting the same from decay or injury. (Parliament 1882:3)

Provisions were also made in the Act of 1882 for the exaction of appropriate penalties from anyone convicted of injuring or defacing a monument covered by the Act. The stiffest penalty that could be imposed was a prison sentence of one month with hard labour. Some offenders, however, might have preferred this to the alternative penalty:

To forfeit any sum not exceeding five pounds, and in addition thereto to pay such sum as the court may think just for the purpose of repairing any damage which has been caused by the offender. (Parliament 1882:4)

In Ireland the three Commissioners of Public Works—a triumvirate incorporated by the Public Works (Ireland) Act of 1831—were appointed to discharge the duties laid out in the Act of 1882. The Board of Public Works, which was comprised of these Commissioners, was the forerunner of today's Office of Public Works. The Irish architect Thomas Newenham Deane was Ireland’s first Inspector of National Monuments.

A Schedule appended to the Act of 1882 listed the sixty-eight sites that were initially covered by the Act (more would be added by subsequent legislation): 26 in England, 21 in Scotland, 3 in Wales, and 18 in Ireland. Listed among the Irish sites was the following entry:

The tumuli, New Grange, Knowth and Dowth (Parliament 1882:11)

Under the Ancient Monuments Protection Act 1882, the Board of Public Works was impowered to dispose of Newgrange in whatever manner it considered to be in the best interests of the monument. If, under advisement from the Inspector of National Monuments, the Commissioners determined that the best means of maintaining Newgrange was to dismantle it and reconstruct it on the opposite bank of the River Boyne, they could do just that—and without fear of legal repercussions.

It is often remarked that with great power comes great responsibility : it is equally true that with great power comes great temptation. The Act of 1882 placed a great responsibility on the shoulders of the Commissioners and their successors, and for the most part they have lived up to that responsibility. But the temptation to rebuild—restore is the preferred euphemism—rather than maintain or preserve has often proved too strong to resist. There is a thin line between vandalism and restoration. One wonders whether the original builders of Stonehenge or Newgrange would even recognize their handiwork in the tourist traps that now stand on Salisbury Plain and the banks of the Boyne.

Newgrange Under Attack

In 861 Newgrange was plundered by a party of Viking raiders from Dublin—Danes—and their Irish allies:

Amhlaeibh, Imhar, and Uailsi, three chieftains of the foreigners; and Lorcan, son of Cathal, lord of Meath, plundered the land of Flann, son of Conang. The cave of Achadh-Aldai, in Mughdhorna-Maighen; the cave of Cnoghbhai; the cave of the grave of Bodan, i.e. the shepherd of Elcmar, over Dubhath, and the cave of the wife of Gobhann, at Drochat-atha, were broken and plundered by the same foreigners. (O’Donovan 497)

John O’Donovan, who was responsible for the preceding translation, added the following explanatory notes:

Achadh Aldai: i.e. the Field of Aldai, the ancestor of the Tuatha-De-Danann kings of Ireland. This place is described by the Four Masters as situated in the territory of Mughdhorna-Maighen, now the barony of Cremorne, in the county of Monaghan; but it is highly probable, if not certain, that Mughdhorna-Maighen is a mistake of transcription for Mughdhorna-Breagh, and that Achadh-Aldai is the ancient name of New Grange, in the county of Meath. If this be admitted, the caves or crypts plundered by the Danes on this occasion were all in the immediate vicinity of the Boyne. It should be here remarked that all the crypts plundered by the Danes on this occasion were in one territory, namely, in the land of Flann, son of Conang, one of the chieftains of Meath; and that it is evident from this that Mughdhorna-Maighen is an error of the Four Masters, as that territory is in Oriel, many miles north of the land of Flann, son of Conang. The Editor deems it his duty to record that these mounds were first identified with these passages in the Annals by Dr. Petrie, in his Essay on the Military Architecture of the ancient Irish, read before the Royal Irish Academy, January, 1834. (O’Donovan 496-497)

In an earlier article in this series, I asked the question: What, in the opinion of John O’Donovan, was the ancient name for Newgrange? Now I have my answer: Achadh Aldai.

Cnoghbhai: Now Knowth, in the parish of Monknewtown, near Slane, in the county of Meath. It is separated from Ros-na-righ by the River Boyne… (O’Donovan 497)

Elcmar: He was son of Dealbhaeth, a Tuatha-De-Danann prince. (O’Donovan 497)

Dubhath: Now Dowth, on the River Boyne, near Drogheda, in the county of Meath. The cave referred to in the text is in a remarkable mound, 286 feet high. The interior of this mound has been recently examined by the Royal Irish Academy, who have found that the cave had been, at some remote period, broken into and disturbed. The Danes seem to have been aware of the traditions of the country, that these mounds were burial places, and that they contained treasures worth digging for. For a description of the recent exploration of this cave see Wakeman’s Handbook of Irish Antiquities. (O’Donovan 497)

The cave of the wife of Gobhann, at Drochat-Atha: This cave is in the great mound at Drogheda, on which now stands a fort which commands the town. (O’Donovan 497)

Sometime in the Middle Ages, long after it had fallen into disuse, Newgrange became overgrown with trees and was forgotten. It was rediscovered in 1699, when the local landowner Charles Campbell, not realizing that it was an artificial structure, quarried stones from it to repair a nearby road. Since then Newgrange was repeatedly damaged by well-meaning antiquaries as much as evilly-disposed visitors—as the archaeologist Michael J O’Kelly would later characterize 19th-century tourists who added their graffiti to the monument (O’Kelly 39).

In 1770, Thomas Pownall complained of the damage being done to Newgrange by the local inhabitants:

The pyramid [ie Newgrange], in its present state, is, as I said, but a ruin of what it was. It has long served as a stone quarry to the country round about. All the roads in the neighbourhood are paved with its stones; immense quantities have been taken away. (Pownall 253)

It is a wonder there was anything left to preserve by the time Parliament decided to step in and take matters into its own hands.

Newgrange Under Repair

Shortly after the passage into law of the Ancient Monuments Protection Act 1882, the Board of Public Works carried out its first conservation work at Newgrange:

At Newgrange, orthostats and lintels were shored up with concrete and wooden beams; an iron gate at the entrance was probably also fitted at this time. The removal of earth from in front of the kerbstones, including the large carved entrance stone, created a bank and ditch effect that is still visible along parts of the monument. Repairs were also made to a drywall revetment on top of the kerb that seems to have been erected in the 1870s (O’Kelly 40). At Dowth, extensive conservation work included construction of a vertical shaft and iron ladder, as well as supports in the northern tomb chamber and a concrete roof in the southern tomb. (Smyth 12-13)

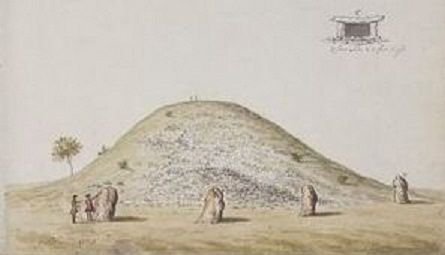

It is instructive to compare Newgrange, the World Heritage Site of today, with the monument as it appeared in 1775, when the Dutch artist Gabriel Beranger was commissioned by William Conyngham of Slane Castle to sketch the three great tumuli of the Boyne Valley.

Even as late as 1962, when Michael J O’Kelly began his restoration work, Newgrange bore little resemblance to its modern appearance. The following photograph was taken, I believe, in the 1930s. Note the presence of trees on top of the mound and the absence of the monument’s quartz wall.

The quartz wall is such a distinctive feature of Newgrange today that it comes as quite a shock to learn that it is a relatively recent and controversial addition.

To be continued ...

References

- Parliament, An Act for the Better Protection of Ancient Monuments, 1882, Chapter 73, London (1882)

- Parliament, An Act for the Extension and Promotion of Public Works in Ireland, 1831, Chapter 33, London (1831)

- John O’Donovan, Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland, by the Four Masters, Volume I, John O’Donovan (translator & editor), Hodges, Smith & Company, Dublin (1856)

- Thomas Pownall, A Description of the Sepulchral Monument of New Grange, near Drogheda, in the County of Meath, in Ireland, in Archaeologia, Volume II, Pages 236–276, The Society of Antiquaries of London, London (1773)

- Jessica Smyth (compiler & editer), Brú na Bóinne World Heritage Site Research Framework, The Heritage Council, Dublin (2009)

- Michael J O’Kelly, Newgrange: Archaeology, Art and Legend, Thames and Hudson, London (1982)

Image Credits

- Newgrange circa 1882: Robert John Welch, Public Domain

- Graffiti inside Newgrange: Anonymous, Fair Use

- Beranger’s Sketch of Newgrange in 1775: Gabriel Beranger, Public Domain

- Newgrange in the 1930s: © Bill & Maureen Cox?, Fair Use

- Picture Postcard of Newgrange: Bórd Fáilte, Fair Use