- How Old Is Newgrange? (Part 6)

William Gregory Wood-Martin

In the decades following the passage into law of the Ancient Monuments Protection Act 1882, when Newgrange was taken into State care, the most reputable descriptions of Irish antiquities were written by professional archaeologists : but there were still some amateurs who made significant contributions to the field. One of these was William Gregory Wood-Martin.

He was born in 1847 into the wealthy Wood and Martin families of County Sligo. He was educated privately at home, and later in Switzerland, Belgium and at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. While fulfilling his military and political duties—he was Aide-de-camp to Queen Victoria, Edward VII and George V, and High Sheriff of Sligo in 1877—he still found time to write and to pursue his interests in archaeology and fieldwork. Among his works are:

- History of Sligo, Country and Town (1882-1892)

- Lake Dwellings of Ireland (1886)

- The Rude Stone Monuments of Ireland (County Sligo and the Island of Achill) (1888)

- Pagan Ireland – An Archaeological Sketch (1895)

- Traces of the Elder Faiths of Ireland (1902, 1901)

Wood-Martin was a member of the Royal Irish Academy and the Royal Historical and Archaeological Association of Ireland. He died in 1917.

On the face of it, W G Wood-Martin was a modernist. He accepted the emerging principles of modern archaeology—the Three-Age System, for example, and the science of Stratigraphy—and his attitude towards the old Irish manuscripts as repositories of true history was of a decidedly skeptical hue. In Pagan Ireland, he asked whether the early Irish records were authentic:

There is a strange kind of excitement in essaying to unravel a complicated problem, and certainly ample room is afforded to a student desirous of analysing and investigating the so-called history and description of ancient Erin, which has been handed down to us and repeated by writer after writer. The mythical stories by Geoffrey of Monmouth, and other scribes of that school, relative to the colonization and history of England, have long been consigned to the literary waste-paper basket; and why should the extravagant legends related of Ireland be treated with more leniency? To transmit, by oral tradition, a chain of events, extending back in an unbroken order to the Creation, would be an impossibility; we possess also good authority for not giving “heed to fables and endless genealogies,” or to “profane and old wives’ fables!” Writers of the olden school usually commenced histories with fables, the length and extravagance of which was in proportion to their estimate of the importance of the theme; and nothing has tended so much to bring discredit on the proper study of Irish history and Irish antiquities as this exaggeration. (Wood-Martin 1895:61-62)

In the same work, he referred to the archaeologist’s spade as a conclusive solver of problems:

The present school of archaeology is pre-eminently that of the spade; the spade is a great solver of problems, and destroyer of fantastical theories; it must ultimately unfold in its entirety primitive man’s ideas regarding the dead, of the future state, of burial customs, ceremonials, and institutions to which they gave rise; it is precisely at this early stage that the spade has much to tell, for where historical and legendary traditions are absent, the ultimate appeal must be to it. (Wood-Martin 1895:64)

After reading these passages, I assumed that Wood-Martin was a member of the new school of skeptical archaeologists, and that he would place the construction of Newgrange in a remote pre-Celtic Stone Age. I was wrong. It is surprising, in fact, how young he thought the monument was:

The carns of the New Grange group are some of the few prehistoric monuments to which an approximate date may be assigned. Ornamentation had there already commenced. The first germs of architecture are also plainly observable, so that their erection can be fixed from the standpoint of prehistoric archaeology. The discovery of Roman coins outside the tumuli need not be taken into serious consideration when essaying to fix their date. They may have been deposited at any time from the period of their issue from the mint. A Roman coin—a brass of Gallienus—was found in the year 1867. A coin of Valentinian and one of Theodosius had previously been dug up in the same locality.

In 1842 workmen found, within a few yards of the entrance to the souterrain of New Grange, at the depth of two feet from the surface, five gold ornaments, a denarius of Geta, and two other defaced coins. The ornaments are figured in the Archaeologia, vol. xxx., p. 136. They appear to belong to the Late Celtic Period.

The approximate date of the introduction of iron into the southern portion of Britain has been estimated by various authorities at from about two to three centuries B.C.—some writers leaning to an earlier, others to a later period. From this part its use spread slowly northward; but on the whole, it is probable that the knowledge of iron reached Ireland at a much later date directly from the Continent, and not through Britain; so that, allowing a considerable interval for an overlap, it is possible that iron had not advanced into universal use in Ireland, at the very earliest, much before the close of the fourth century of the Christian era, as will be essayed to be shown further on; it is impossible, however, to define any hard and fast line for the commencement of its use. The transition from bronze to iron in a country of such extent as Ireland, divided into hostile populations, must have occupied a period which may be reckoned by centuries. Sir John Evans remarks that “there must have been a time when in each district the new phase of civilization was being introduced, and the old conditions had not been entirely changed;” and of this intermediate stage perhaps no better example could be produced than the evidence of the iron tools and ornamentation left by the tribe who erected the carns on the Loughcrew hills.

From these considerations, as well as from the style of decoration, Mr. George Coffey is inclined to date New Grange approximately about the first century of the Christian era; and, “if anything, would be disposed to reduce that limit rather than extend it,” Fergusson, in his Rude Stone Monuments, conjectures its erection to have taken place towards the close of the third century, so that practically there is very little difference between the two estimates, and if we strike the happy mean and place its origin in the second century, we shall probably arrive at a sound conclusion. The ornamentation at New Grange and Dowth differs, but so does the decoration on the chambers of the Loughcrew hills. The exploration of Knowth, the third great tumulus on the Boyne, may throw more light on the subject ; but it would appear to be probable that no very lengthened period separates Dowth from New Grange. (Wood-Martin 1895:286-288)

Loughcrew, like Newgrange, is now dated to the Neolithic era, making it more than five thousand years old. It is intriguing, then, to find an archaeologist of the late nineteenth century discussing evidence of the iron tools and ornamentation left by the tribe who erected the carns on the Loughcrew hills.

This information, I suspect, will not be found in any textbooks being written today: these monuments, we are assured, were built in the Stone Age by a pre-metallurgic culture, so no mention of iron is warranted. But Wood-Martin is quite clear on the matter:

A pick of iron was discovered in a carn at Sliabh-na-calliaghe [ie Loughcrew], and with it the greater portion of an iron compass adapted for tracing the curvilinear work on the sides of the passages and chambers; iron remains were also found in the New Grange group of carns. In the present state of antiquarian knowledge, it would appear as if gold working and adornment were firmly established before the era of the erection of the sculptured chambers of carns. (Wood-Martin 1895:540)

Why have these findings been reburied? Isn’t it the archaeologist’s job to disinter things, not bury them and hope that they will be forgotten?

A few pages later, Wood-Martin discusses the ancient pretroglyphs inscribed on the stones of these monuments:

Rock scribings until very recently remained unnoticed by antiquaries. A few early writers drew attention to the markings on the walls of the sepulchral chambers of New Grange and a few other localities; but later and meritorious writers are silent on the subject of rock sculpturings, and some were probably ignorant of even their existence. (Wood-Martin 1895:550)

The scribing [on a stone now in the Belfast Museum] is incised, and has the appearance of having been worked out by the aid of a sharply pointed flint or metallic instrument, for lines similarly cut, are found upon stones forming portion of the sides of prehistoric sepulchral chambers. (Wood-Martin 1895:555)

He then makes an pertinent point about the contemporary state of these scribings:

It is now unfortunately impossible to collate these drawings [of ancient Irish petroglyphs] with the originals, in the expectation of proving, or disproving, their accuracy. The process of decay in the outer laminae of the scribed slabs was very observable, even in the first explorer’s time. On the stones, which had been long exposed to the destructive effects of the atmosphere, the punched work was often much obliterated, but on those but recently exposed the mark of the tool was almost as fresh and distinct as at the period of its execution. It is greatly to be desired that the sculptured portions of all subaerial prehistoric tombs, or cists, should be removed to a museum, as lengthened exposure to climatic influences has already played sad havoc with the designs. (Wood-Martin 1895:563)

If these monuments are more than five thousand years old, is it not strange that their petroglyphs managed to survive in an excellent state of preservation for about forty-eight centuries, before rapidly deteriorating over a period of just two or three centuries?

George Coffey

Unlike Wood-Martin, one of the authorities cited by him in Pagan Ireland, George Coffey, was a professional archaeologist—probably the first Irish archaeologist of international standing (Waddell 3). He was also the first Keeper of Antiquities at the National Museum of Ireland. Between 1890 and 1912 he published several works on Newgrange and other Irish megalithic structures.

Wood-Martin cited Coffey as placing Newgrange approximately about the first century of the Christian era. This was indeed Coffey’s opinion in 1890-91, when he made several visits to Newgrange. In his paper On the Tumuli and Inscribed Stones at New Grange, Dowth, and Knowth he concluded that the monument belonged to the transitional period between the Bronze and Iron Ages:

On the whole, although a knowledge of iron may have reached Ireland earlier, I do not think we can safely place an extended use of that metal much farther back than the first century of our era, or possibly first century B.C. The full development of “Late Celtic” ornament will be somewhat later.

From these considerations I am inclined to date the tumulus at New Grange approximately about the first century, and, if anything, would be disposed to reduce that limit rather than extend it ... I do not think, however, that the date of New Grange can be brought so late as Fergusson, in “Rude Stone Monuments,” conjectures, viz. the end of the third century. The ornament preserves too close a contact with that of the true Bronze Period to permit of so late a date. (Coffey 1892:71)

In its one-hundred-and-two pages, this paper, which appeared in The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy in 1892, includes a very interesting review of the literature on Newgrange from earliest times to the late nineteenth century. It is well worth reading.

Twenty years later, Coffey had come to believe that Newgrange was a Bronze Age artifact, and that its construction was influenced by Bronze Age cultures of Ægean and Scandinavian provenance (Coffey 1912:62):

Some discussion as to the absolute chronology of the Bronze Age in Ireland will, no doubt, be expected, though any attempts to give actual dates can only be approximate ... The doyen of prehistoric archæology, Dr. Oscar Montelius,of Stockholm, has been the pioneer of the study of the prehistoric chronology of Europe ... More recently (1908) he has put forward the chronology of the British Islands in a notable memoir published in Archæologia. It may be mentioned that Dr. Montelius visited Ireland some years ago, and speaks with the greater authority as having personally examined the actual Irish evidence.

In this memoir Dr. Montelius divides the Bronze Age of Great Britain and Ireland into five periods, and includes in his first period the transitional time when copper was in use (Copper Period), which he places at from the middle of the third to the beginning of the second millennium B.C. Now, though the division of the Irish Bronze Age into five periods may be accepted, we should hardly care to place the first period as early as Dr. Montelius suggests; and without going into the question of the time at which the period commenced, we might take the period of its ending at from about 2000-1800 B.C. In this period would be included the flat copper celts of early form, copied from the stone celts of the preceding Neolithic Period, some few small, flat knife-daggers of copper, and the earliest of the halberds. Stone implements, no doubt, remained largely in use; and the very finely decorated hammer-axes probably belong to this period ... (Coffey 1913:2-3)

The fourth period, which was long, and during which a considerable development takes place, might be placed at from 1280 to 900 B.C. This period includes the later type of celts with increased stop-ridge and flanges (palstaves), and some of the earlier forms of socketed celts, long rapiers, the earlier type of leaf-shaped swords, and the looped and leaf-shaped spear-heads, gold torcs, and possibly some of the bronze fibulæ, and sickles without sockets; the disk-headed pins and bronze razors may be placed either at the end of this time or the beginning of the next period. In this period must also be placed the

building of the great tumuli of the New Grange group. (Coffey 1913:4)

The similarity between New Grange and the tholos tombs of the mainland of Greece is so striking that it is at least likely that the former may have been derived from the latter ... Now if New Grange is derived from this source, it cannot well be placed earlier than 1000 B.C. (Coffey 1913:101 ... 103)

Coffey had succumbed to continental ideas, and accepted the newfangled theories of Oscar Montelius. For the second time in its history, Newgrange had been plundered by the Scandinavians.

Like Wood-Martin, Coffey also recorded some pertinent remarks on the state of preservation of incised inscriptions at Newgrange. In the following extract he was quoting Richard Clark of the Geological Survey of Ireland, who accompanied him on one of his visits to the monument:

“The passages and chambers of the two mounds [Dowth and Newgrange] have been formed of large slabs of the Lower Silurian rocks, which crop up within a few miles’ distance. They were apparently either rudely quarried for the purpose, or split from surface rocks. With the exception of some of the stones in the passage and others of the upright course, the slabs in the interior of New Grange show little traces of the original weathered surface of the rocks from which they were taken, but, on the contrary, even faces, which indicate that they have been split along the cleavage,and care taken in their selection. The spiral carvings have been cut exclusively on this description of stone; and, considering the exposed positions of the external slabs, they show but little effect of weathering.” (Coffey 1892:17)

James Fergusson

The other authority cited by Wood-Martin in Pagan Ireland in support of his belief that Newgrange was of relatively recent construction was James Fergusson. A Scottish architectural historian, Fergusson is perhaps better known today for his interest in the antiquities of India, where he worked as a partner in a mercantile house. In 1872 he published his study of the megalithic monuments of Europe, Asia and America, Rude Stone Monuments in All Countries: Their Ages and Uses. In this work, he began his account of Ireland’s megaliths with the following critical remarks:

It is probable, after all, that it is from the Irish annals that the greatest amount of light will be thrown on the history and uses of the Megalithic monuments. Indeed, had not Lord Melbourne’s Ministry in 1839, in a fit of ill-timed parsimony, abolished the Historical Commission attached to the Irish Ordnance Survey, we should not now be groping in the dark. Had they even retained the services of Dr. Petrie till the time of his death, he would have left very little to be desired in this respect. But nothing of the sort was done. The fiat went forth. All the documents and information collected during fourteen years’ labour [1825-39] by a most competent staff of explorers were cast aside—all the members dismissed on the shortest possible notice, and our knowledge of the ancient history and antiquities of Ireland thrown back half a century, at least. (Fergusson 175)

Guided by the literary traditions of the country, Fergusson was happy to accept that the Boyne Valley Complex was a royal cemetery of Celtic Ireland:

There is no doubt but that many similar passages to these might be found in Irish MSS., if looked for by competent scholars, that these extracts probably are sufficient to prove two things. First, that the celebrated cemetery at Brugh, on the Boyne, six miles west from Drogheda, was the burying-place of the

kings of Tara from Crimthann (A.D. 84) till the time of St. Patrick (A.D. 432), and that it was also the burying-place of all those who were concerned—without being killed—in the battles of Moytura. We are not, unfortunately, able to identify the grave of each of these heroes, though it may be because only one has been properly explored, that called New Grange, and that had been rifled before the first modem explorers in the seventeenth century found out the entrance. The Hill of Dowth has only partially been opened. The great cairn of Knowth is untouched, so is the great cairn known as the Tomb of the Dagdha. Excavations alone can prove their absolute identity; but this at least is certain, we have on the banks of the Boyne a group of monuments similar in external appearance at least with those on the two Moytura battle-fields, and the date of the greater number of those at Brugh is certainly subsequent to the Christian era. (Fergusson 191-192)

Fergusson calculated that the two battles of Moytura took place around 30-20 BCE (Fergusson 193).

William Copeland Borlase

William Copeland Borlase was a wealthy Cornish aristocrat, who initially pursued a legal and political career. Between 1880 and 1887 he represented the constituents of East Cornwall and St Austell in Parliament as a member of the Liberal Party. Bankruptcy and a political scandal, however, forced his resignation. Disowned by his family, he moved to Ireland and gave himself up to his antiquarian interests.

Over the next ten summers, he travelled the length and breadth of the country, cataloguing and describing its extensive heritage of megalithic tombs—or dolmens, as he referred to them, irrespective of size or structure. He also researched and recorded the local myths and traditions associated with them. The result of this indefatigable labour was a monumental work in three volumes, The Dolmens of Ireland.

Although his description of Newgrange relied heavily on Coffey’s 1892 paper and quoted extensively from it, Borlase disagreed with Coffey on a number of salient points. Most notably, he believed that the monument was constructed in the earliest phase of the Bronze Age.

... granted the superior antiquity of the monument [Newgrange], which may I think be assigned to the Bronze Age and perhaps to an early period of it, as we shall see in the sequel ... (Borlase 356)

... the spiral carvings, as at New Grange, which are more probably referable to Bronze Age Art, borrowed from southern patterns, and are purely ornamental. (Borlase 847)

Some of the stones [of the French megalithic tomb of Des Mauduits] showed sculpturing something after the manner of that at New Grange, and the whole is referable to the early Bronze Age. (Borlase 961)

For the structural details and decoration at New Grange, we have to look to Scythia and Greece in the Bronze Age ... New Grange is architecturally and in point of ornament a barbarian copy of a Græco-Scythian tomb. (Borlase 1167)

Who these Bronze Age builders were he was not sure, but they were probably pre-Celtic:

That the tendency of modern research, and the views I have myself formed, is distinctly to decelticize the monuments of the dolmen class matters not; the fact remains that although we know not, nor ever can know, what the language was which the builders of the earliest dolmens spoke, the absolute identity of the remains they have left us, and which time has been powerless to efface, proves them to have been one and the same people, as far, at all events, as the British Islands are concerned. (Borlase vii-viii)

By far the most perplexing question which I have encountered is that of assigning, however indefinitely, any even approximate date for the introduction of the Celtic language into the British Isles. With a boldness which I confess may be rash, I state my belief that it may have arrived there as early as the best period of the Bronze Age as estimated by MonteIius (see p. 525 [ie 1250–1050 BCE]). It was not, therefore, the language of the earliest dolmen-builders, but, having become rooted in the islands, it became, in Ireland especially, the language both of the more primitive inhabitants on the one hand, and of immigrants on the other—who, pouring in from the Baltic and the German Ocean, took up their abode on Irish soil. (Borlase xv)

To be continued ...

References

- W G Wood-Martin, The Rude Stone Monuments of Ireland (Co. Sligo and the Island of Achill), Hodges, Figgis & Co, Dublin (1888)

- W G Wood-Martin, Pagan Ireland, An Archaeological Sketch: A Handbook of Irish Pre-Christian Antiquities, Longmans, Green & Co, London (1895)

- John Waddell, The Prehistoric Archaeology of Ireland, Wordwell Ltd, Bray (2000)

- George Coffey, On the Tumuli and Inscribed Stones at New Grange, Dowth, and Knowth, The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, Volume 30 (1892-1896), pp 1-96, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1892)

- George Coffey, New Grange (Brugh na Boinne) and Other Incised Tumuli in Ireland, Hodges, Figgis & Co Ltd, Dublin (1912)

- George Coffey, The Bronze Age in Ireland, Hodges, Figgis & Co Ltd, Dublin (1913)

- Oscar Montelius, The Chronology of the British Bronze Age, Archaeologia, or Miscellaneous Tracts Relating to Antiquity, Volume 61, Issue 1, January 1908, pp 97-162, The Society of the Antiquaries of London, London (1908)

- James Fergusson, Rude Stone Monuments in All Countries: Their Ages and Uses, John Murray, London (1872)

- William Copeland Borlase; The Dolmens of Ireland, Volumes I-III, Chapman & Hall, London (1897)

Image Credits

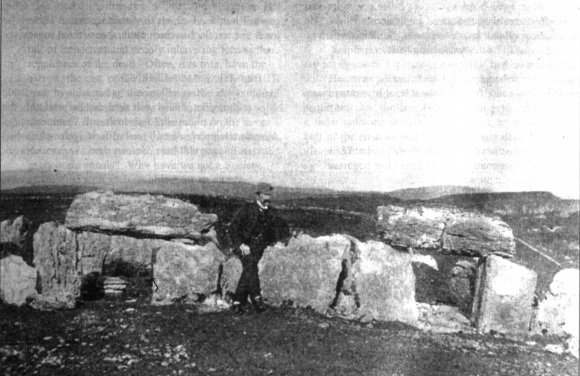

- Newgrange in 1890: George Coffey, Public Domain

- William Gregory Wood-Martin: Pagan Ireland, Public Domain

- George Coffey: Plan and Section of Chamber at Newgrange: George Coffey, Public Domain

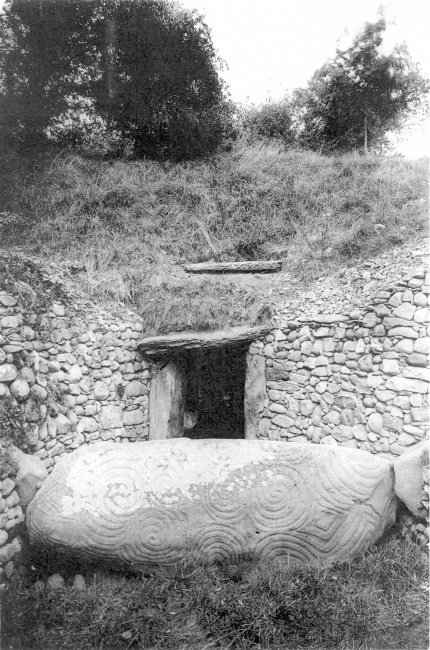

- Entrance to Newgrange in 1890: George Coffey, Public Domain

- James Fergusson: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

- William Copeland Borlase: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain